INDIA:

Discussions and debates, critiques and readings, held at haunts of Urdu books and writing around the country have been interrupted rudely.

In Malegaon

On the first Saturday of every month, the textile city of Malegaon in northern Maharashtra used to become home for lovers of Urdu literature, who meet to discuss, debate and critique new writings in the language, mostly by local writers. Organised under the aegis of Anjuman Muhibban e Adab (Association of Literature Lovers), the gathering began at around 9 pm, and went on till midnight.

Between 30 and 50 people – both writers and readers – would come together, a number that would at times go up to as many as 100 or even 150. Asif Iqbal Mirza, the secretary of the Anjuman, said the practice began 25 years ago on the suggestion of local journalist and editor Samiullah Ansari, who published new Urdu fiction in his weekly, Hashmi Awaz.

Over the years, the publication had emerged as a popular local magazine for young and budding writers to publish their works. The weekly, now in its 35th year of publication, had a considerable fan following and readership at the time. Ansari then suggested that admirers of the magazine form a group comprising readers as well as writers.

The group was initially named Anjuman Muhibban e Hashmi Awaz (Association of Admirers of Hashmi Awaz), but within a few years, its following grew to encompass more than just the readers of the magazine, and in 1998 it was rechristened Anjuman Muhibban e Adab, Malegaon. “Ansari sahib formed the Anjuman so that writers could get their new works critiqued by readers before getting them published in the weekly,” Mirza ssid.

Back then, Mirza himself wrote for a local children’s newspaper called Khair Andesh. But his association with the Anjuman helped him grow into a prolific Afsana Nigar, a short story writer. He was 17 when the group was formed; in the past 25 years, he has written and published more than 200 short stories in different publications.

Apart from Anjuman Muhibban e Adab, there are two more literary groups in Malegaon that held regular meetings until the lockdown was declared in March. No such meetings have been held since then. “Unlike earlier, we now have enough time to read and write. But the irony is we don’t have the opportunity to discuss and publish them,” said Mirza, who also runs a printing business. Several local publications had to halt their issues, including Hashmi Awaz, owing to the lockdown.

According to Mirza, although social media outlets such as WhatsApp and Facebook have, to some extent, helped to keep in touch with fellow writers and readers, the literary life of Malegaon has come to a standstill, since a large number of local writers and readers came from the working class and worked in local looms. “The year 2020 is the silver jubilee of my literary career. I had plans to publish a collection of my short stories, but thanks to the pandemic, that will not happen this year,” Mirza said with a great sense of despair.

In Mumbai

Both readers and writers have felt a deep loss during the pandemic. His love of books took Shakeel Rasheed, editor of the Urdu daily Mumbai Urdu News, to various bookshops in and around the Mohammad Ali Road area of Bombay. “Visiting bookshops was a part and parcel of my life. I feel a deep loss when I don’t visit them,” he said. For him, bookstores are not just spaces to buy books, but they also served as addas for readers and writers. As soon as some relaxations were in place, he rushed to the stores. “Par ab pahle wali baat nahi rahi,” said Rasheed. “Things are not as they were before.” The pandemic has made it more difficult to meet new people.

Shadab Rashid’s Kitabdaar publications and bookstore in Temkar Street of Nagpada was one such adda for Urdu writers in Mumbai, as was Maktaba Jamia on Sandhurst Road West. Today, Kitabdaar and a few other bookshops have opened their stores for a few hours every few days, while Maktaba Jamia remains closed. “Due to lack of public transport and fear of the pandemic, people cannot come to Kitabdaar,” Shadab said. He also edits the quarterly literary magazine Naya Waraq, founded by his late father and noted journalist and writer Sajid Rasheed.

Shadab Rashid said the lockdown brought significant hardships and losses to Urdu publishers and distributors. “It is not that people don’t want to read Urdu books anymore – the problem is they cannot buy them,” he said. “I have received lots of online orders, but I cannot fulfill them because I rely on postal services as they are the cheapest means of delivery, but the services are not fully functional yet.” His online Urdu bookshop kitabdaar.com is one of the few digital distribution platforms for Urdu books exclusively in India. Another such platform, urdubazaar.in, was recently launched from Delhi.

Owing to the discontinuation of physical interactions between readers and writers, people have lost touch with each other, since not all Urdu writers are active on social media, Shakeel Rasheed told me. “We have lost many good writers during this period and found out about their demise several days later,” he added. “Moreover, we could not participate in their last journeys.”

In Hyderabad

Another writer recounted similar thoughts after the death of noted Urdu satirist Mujtaba Hussain in Hyderabad on May 27. Hussain was awarded the Padma Shri in 2007 for his contributions to Urdu literature, but in December 2019, he announced he was returning the award to protest the enactment of the contentious Citizenship Amendment Act. “[T]he democracy for which I fought is under attack now and the government is doing that,” he had said, “that’s why I don’t want to associate the government with me.”

In Hyderabad, another centre of Urdu writing, literary activities have come to a similar halt due to the pandemic. Publications like Shagoofa, a monthly magazine of satirical writing, have been temporarily discontinued since the lockdown.

In Delhi

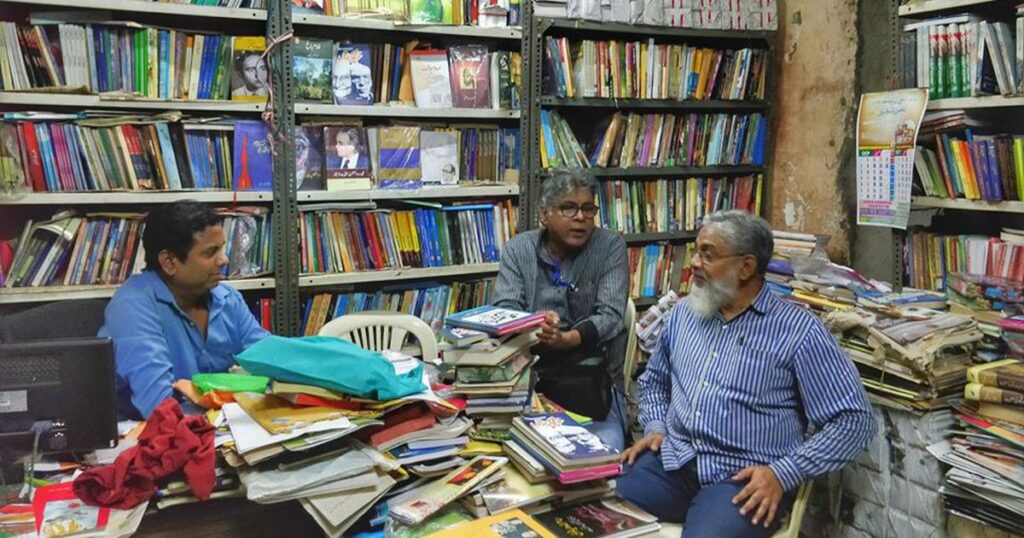

In Delhi, too, the pandemic has left an adverse impact on Urdu writing. Khan Rizwan, a poet and a known “addebaaz” from Delhi, loved participating in and organizing adabi addas (literary gatherings). He misses visiting the Nai Kitab book store, located in one of the many bylanes of Jamia Nagar, which is one of the famous addas for Urdu lovers in the city. Run by veteran writer and publisher Shahid Ali Khan, Nai Kitab is a haven for young and old writers alike, Rizwan said, as Shahid sahib treated them alike. “It is not just a bookshop but an institution where one got to meet noted writers and lovers of Urdu literature,” he said.

Rizwan would visit the shop at least twice a week, and meet a new literature enthusiast or writer, or find out about a new book or risala /parcha (journal/magazine). “I miss the black tea and chips that Shahid sahib served us with love and affection,” he recalled. “He is a storehouse of information, and several veteran writers were his friends, so he would tell us stories all the time.”

I couldn’t agree more with Rizwan. I have been visiting Nai Kitab once every few months for more than a decade now, and on each of my visits, after asking khabar-khairyat, Shahid sahib would say, “Achcha aap bahut dino baad aayen hain, ye nayi kitaabein aayi hai dekh lein (Since you’ve come after a long time, here are some new books).” Last year, when I visited the bookshop around this time, he directed me towards dozens of books written by noted Urdu satirist Fikr Taunsvi and Shaukat Thanvi. I immediately bought all of them, as they were usually out of print and seldom available.

As the person in charge of the Maktaba Jamia, the publication division of Jamia Millia Islamia in Bombay, Shahid Sahib befriended writers and poets like Jan Nisar Akhtar, Meena Kumari, Sahir Ludhianvi and Jagan Nath Azad. Some of them were regular visitors to the Maktaba Jamia. Though he moved to Delhi after serving the Maktaba for several decades, he did not stop hosting literature lovers. He then founded Nai Kitab publishers and a quarterly journal by the same name.

It was in 2007 at his bookshop that I first chanced upon Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s celebrated novel Kai Chand The Sare Aasman, later translated into English as The Mirror of Beauty by the author himself. The novel went on to become a major critical and commercial success.

Faruqi was also associated with the Nai Kitab journal as chairperson of its advisory council and would visit the shop once in a while. The journal eventually stopped publication owing to Shahid sahib’s failing health, but he continued with the bookstore as it was like “oxygen for him”, he had once told me.

Waiting for freedom

Some writers have managed to turn the lockdown into a creatively productive period. “Personally, the pandemic has proved as a blessing in disguise as I read books I wanted to for years and finish other important work, such as recording videos of Urdu literature lectures,” says Khalid Mubashir, a poet and assistant professor of Urdu literature at Jamia. He quickly added, however, this was not common, as most writers and poets were stuck at home, either because of their age or in fear of the pandemic. “Moreover, not all writers have access to technology and books like I do. I am fortunate enough to have friends who helped me with technology to do something substantial during this period.”

Mubashir’s videos, as many as 60 of them, are each about 30 minutes long, and cover the history, evolution and development of Urdu and its literature in the subcontinent. Though the lectures are prepared keeping in mind the need and syllabus of Urdu literature students, ordinary Urdu lovers can also benefit from them. All lectures are available on the YouTube channel Safeer e Adab.

Similarly, although younger poets like Mohammed Anas Faizi from old Delhi have been trying to keep Urdu literature gatherings going by using social media, online addas do not have the feel and impact of offline and in-person gatherings. “Technology and social media can only help to a certain extent. Online gatherings, mushairas and addas cannot substitute for the real ones, no matter how well they are done,” he said.

With apologies to Faiz Ahmad Faiz, what the Urdu writers, poets and addebaaz seem to be telling the pandemic is:

Gulon Mein Rang Bhare Baad e Nau Bahar Chale

Chale Bhi Jao Ki Gulshan Ka Karobar Chale

Mahtab Alam is a multilingual journalist and until recently was the executive editor of The Wire Urdu. His Twitter handle is @MahtabNama.

This series of articles on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on publishing is curated by Kanishka Gupta.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll.in / Home> Publishing and the Pandemic / by Mahtab Alam / July 14th, 2020