INDIA:

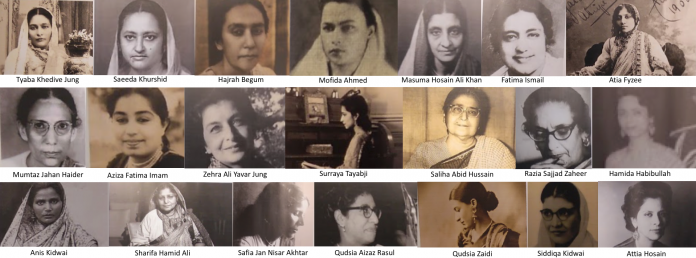

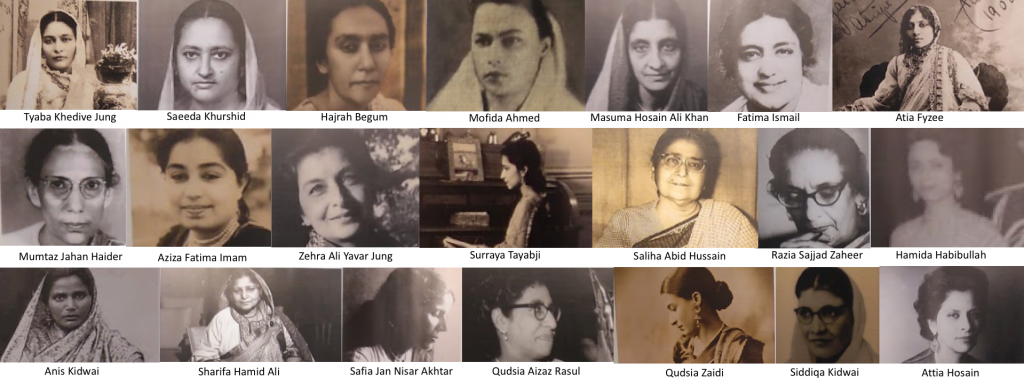

Several Muslim women were an active part of India’s freedom struggle, some of whom emerged from Hyderabad.

The list includes Abadi Bano Begum, Bibi Amtus Salam, Begum Anis Kidwai, Begum Nishatunnisa Mohani, Baji Jamalunnisa, Hajara Beebi Ismail, Kulsum Sayani, and Syed Fakrul Hajiya Hassan.

As India celebrates 75 years of Independence the country often recalls those that were instrumental in the country’s freedom struggle. But often those who aren’t talked about enough evanesce into the archives of history.

As men who took lead roles in the movement were put behind bars, the women ensured that the movement would not die down and the country attained the freedom a vast majority of it’s residents and citizens enjoy today.

The country’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his Independence Day speech, on Monday, hailed women and the part they played during the times including, Rani Laxmibai, Jhalkari Bai, Durga Bhabhi, Rani Gaidinliu and Begum Hazrat Mahal among others.

These are a few among the many names that are a part of the country’s Independence struggle. Apart from Begum Mahal, who made it to the list of the PM’s speech, today, Muslim women have made their mark in Indian history.

Abadi Bano Begum, Bibi Amtus Salam, Begum Anis Kidwai, Begum Nishatunnisa Mohani Baji Jamalunnisa, Hajara Beebi Ismail, Kulsum Sayani, and Syed Fakrul Hajiya Hassan are among those who are often forgotten or lost in public memory.

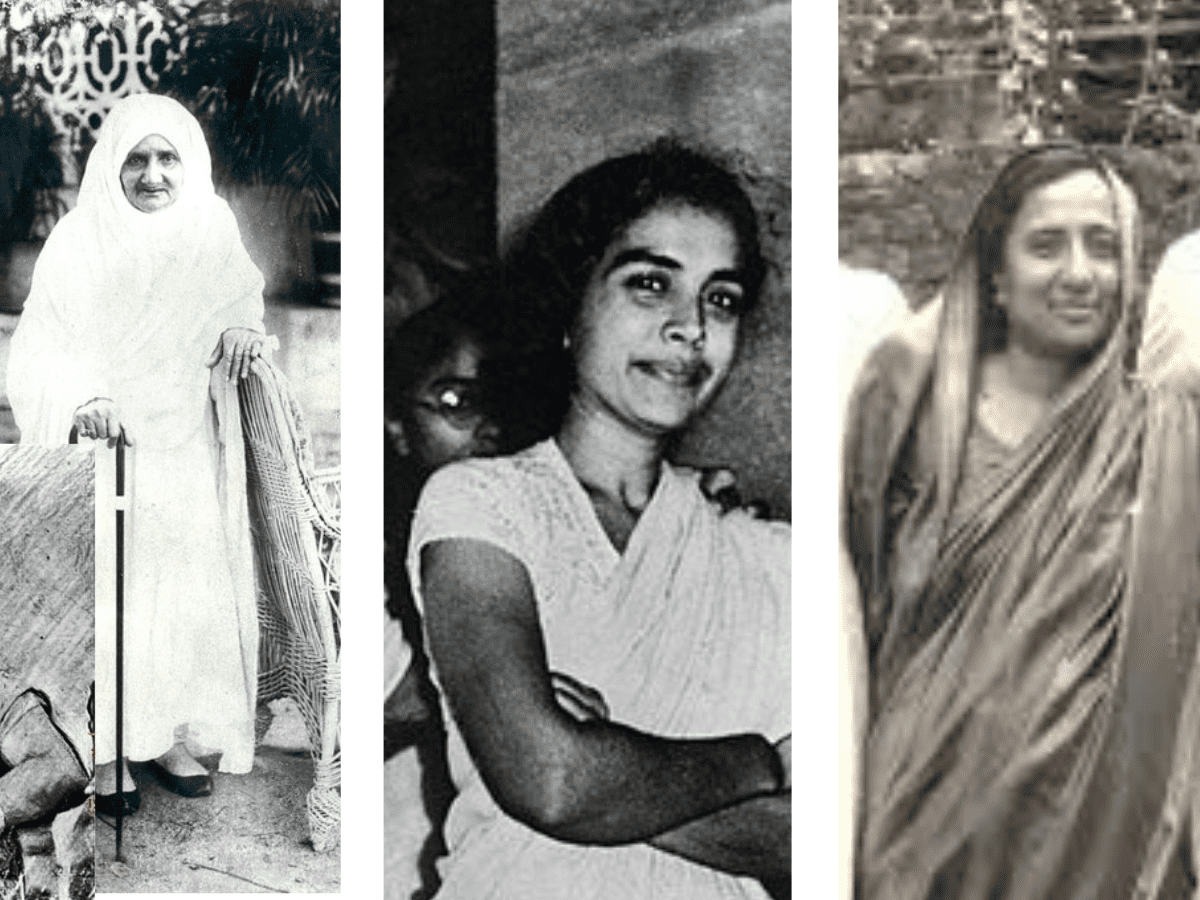

Abadi Bano Begum (Born 1852- Died 1924)

Abadi Bano Begum was the first Muslim woman who actively took part in politics and was also a part of the movement to free India from the British Raj. Abadi Bano Begum referred to by Gandhi as Bi Amma, was born in 1852, in Uttar Pradesh’s Amroha.

Bi Amman was married to a senior official in the Rampur State, Abdul Ali Khan.

After the death of her husband, Bano raised her children (two daughters and five sons) on her own. Her sons, Maulana Mohammad Ali Jouhar and Maulana Shaukat Ali become leading figures of the Khilafat Movement and the Indian Independence Movement. They played an important role during the non-cooperation movement against the British Raj.

Bi Amma, despite her poor financial condition, from 1917-1921, donated Rs 10 every month to protest against the British Defense Act, after Sarojini Naidu’s arrest.

In 1917, Bano also joined the agitation to release Annie Besant and her sons, who were arrested by the British after their failed attempts to silence her home rule movement in 1917, launched alongside, Bal Gangadhar Tilak.

Despite being a conservative Muslim for the most part of her life Bi Ammah was one of the most prominent faces of Muslim women in India’s freedom struggle.

To get the support of women, Mahatma Gandhi encouraged her to speak in a session of the all-Indian Muslim league, she gave a speech which left a lasting impression on the Muslims of British India.

Bano played an important role in fundraising for the khilafat movement and the Indian Independence movement.

Bibi Amtus Salam (Died 1985)

Mahatma Gandhi’s ‘adopted daughter’ from Patiala Bibi Amtus Salam was a social worker and his disciple who played an active role in combating communal violence in the wake of the partition and in the rehabilitation of refugees who came to India following the partition.

She has on several occasions risked her life by rushing to sensitive areas during the communal riots in Calcutta, Delhi and Deccan.

Bibi Salam was a Muslim inmate of the Gandhi ashram and had over time become an adopted daughter to Gandhi.

After the Noakhali riots, an article published in The Tribune on February 9, 1947, noted that Amtus Salam’s 25-day fast, which was intended to make offenders feel guilty, was one of the most significant outcomes of Gandhi and his disciples’ actions.

To protest the “negligence” of the state authorities in the effort to rescue kidnapped women and children, she sat on an indefinite fast at Dera Nawab in Bahawalpur.

Begum Hazrat Mahal (Born 1820-Died 1879)

An iconic figure of the 1857 uprising, Begum Hazrat Mahal fought against the British East India Company.

Begum, the wife of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the ruler of Awadh, refused to accept any favours or allowances from the British. Begum, with the aid of her commander Raja Jailal Singh, battled the British East India Company valiantly.

Muhammadi Khanum, the future Mahal, was born in Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh, in 1830. Gulam Hussain is her father. She had an early understanding of literature. The East India Company’s destruction of mosques and temples to make room for highways served as the catalyst for her uprising.

When the British East India Company invaded Awadh in 1856 and her husband, the last Nawab of Awadh, was exiled to Calcutta, the Begum made the decision to remain in Lucknow along with her son, Birjis Qadir.

On May 31, 1857, they convened in Lucknow’s Chavani neighbourhood to declare Independence and drive the British out of the city.

On July 7, 1857, Begum Hazrat Mahal proclaimed her son, Birjis Khadir, the Nawab of Awadh. She raised 1,80,000 soldiers and lavishly renovated the Lucknow fort as the Nawab’s mother.

She died there on 7 April 1879.

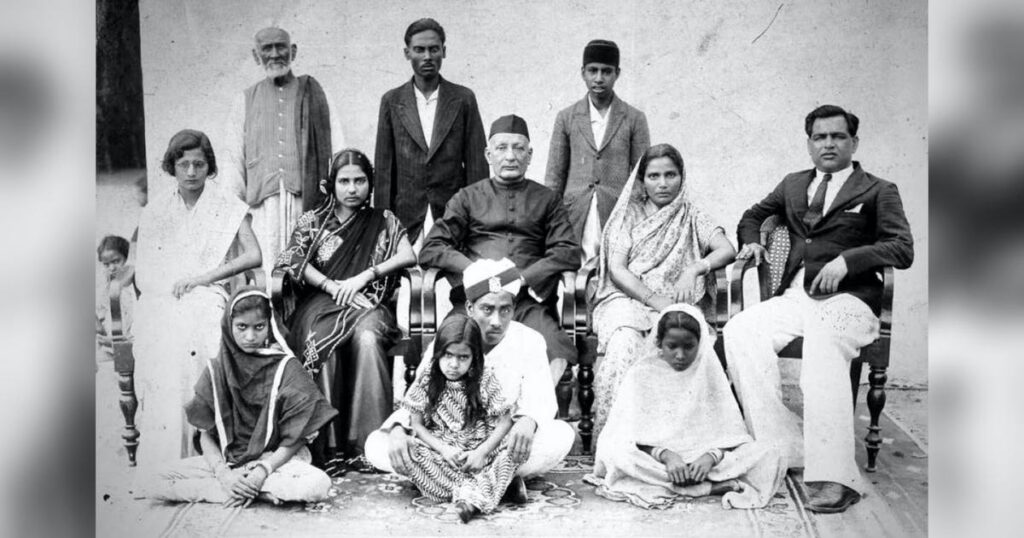

Begum Anis Kidwai (Born 1906- Died 1982)

A politician and activist from Uttar Pradesh (UP) named Anis Kidwai devoted most of her life to serving the newly Independent India, working for peace and the rehabilitation of the victims of the terrible partition of India.

She represented the Indian National Congress (INC) in the Rajya Sabha from 1956 to 1962, serving two terms as a Member of the Parliament.

Anis Begum Kidwai remained active during the Indian National Movement. Despite gaining independence in 1947, India suffered from country division.

By then, her husband Shafi Ahmed Kidwai had been murdered by communal forces for his efforts to promote amity between Muslims and Hindus and to prevent the split of the country. She was deeply devastated by her husband’s passing.

She visited Mahatma Gandhi in Delhi following her husband’s passing as a result of this unfortunate tragedy.

In order to support and assist the women who were suffering similarly to her as a result of the country’s separation, she began working with women leaders like Subhadra Joshi, Mridula Sarabhai, and others under the direction of Mahatma Gandhi.

She also started rescue camps for the victims and supported them in all respects. They affectionately called her ‘Anis Aapa’. She penned her experiences during the division of the Nation in her book ‘Azadi Ki Chaon Mein’.

Begum Nishatunnisa Mohani (Born 1884- Died 1937)

Begum Nishatunnisa Mohani was born in 1884 in Awadh, Uttar Pradesh, and her notion of ultimate freedom was adopted by Gandhiji.

Married to Moulana Hasrat Mohani, a tenacious independence warrior and the one who gave the phrase “Inquilab Zindabad” its origin. Begum, a fierce opponent of British authority, supported the then-hardliner of the liberation struggle, Bal Gangadhar Tilak.

After his imprisonment for publishing an anti-British piece, she wrote to her husband, Hasrat Mohani, encouraging him and raising his spirits by saying, “Face the risks imposed upon you boldly. Do not give me any thought. No sign of weakness should come from you. ‘Be careful’.”

Later, when her husband was in prison, she took over the publication of his daily, Urdu-e-Mualla, and engaged in various legal disputes with the government.

Baji Jamalunnisa, Hyderabad (Born 1915- Died 2016)

Baji Jamalunnisa, who actively participated in the Telangana armed conflict, passed away in this city on July 22 2016, at the age of 101.

Jamalunnisa Baji was born in Hyderabad in 1915 and was a prominent advocate for racial peace and the independence cause.

She began reading the banned journal “nigar” and progressive literature as a young child after being raised by her parents in a liberal/progressive environment.

Despite being raised in the traditional religious traditions of the Nizam regime, a component of the British Raj, she actively participated in the nationalist movement.

She continued to participate in the independence movement despite the oppressive rule of the Nizam and the British rule over her in-laws’ objections.

Later, she met Maulana Hazrat Mohani (the man who coined the phrase “Inquilab Zindabad” and was known as “Thunder Bolt” in the Freedom struggle), who inspired her to join the anti-imperialist movement in the nation.

She provided sanctuary to freedom fighters trying to avoid being arrested by the Imperial Government while being a communist.

Despite lacking basic higher education, she was fluent in Urdu and English and founded the literary society Bazme Ehabab, which held debates in groups on socialism, communism, and unreasonable customs.

She is buried at the Hazrath Syed Ahmed Bad-e-Pah dargah in First Lancer. She was the sister of Syed Akthar Hasan, a former MLA and the founder of Payam Daily, and was better known as “Baji”.

She was a close friend and member of the Communist Party of Maqdoom Mohiuddin. Baji was also a founding member of the Progressive Writers Association and the Women’s Cooperative Society.

Hajara Beebi Ismail, Andhra Pradesh (Died 1994)

Mohammed Ismail Saheb’s wife, Hajara Beebi Ismail, was a freedom warrior from Tenali in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh.

Mahatma Gandhi had a significant impact on the pair, who committed themselves to the Khadi campaign movement. In the Guntur district, her husband Mohammed Ismail opened the first Khaddar Store, earning him the moniker “Khaddar Ismail.”

Tenali served as the Muslim League’s headquarters during that time in the Andhra area, where it was particularly active.

Since Hajara and her husband supported Gandhi, they encountered fierce hostility from the Muslim League. Despite her husband’s repeated arrests for his involvement in the national movement, Hajara Beebi never lost spirit.

Kulsum Sayani (Born 1900- Died 1987)

On October 21, 1900, in Gujarat, Kulsum Sayani was born. She participated in the Indian National Movement and battled against social injustices.

Kulsum and her father met Mahatma Gandhi in 1917. Since then, she has travelled Gandhi’s path. Throughout the Indian National Movement, she advocated for social changes.

Dr. Jaan Mohamad Sayani, a well-known liberation fighter, was the man she wed. She participated actively in a number of events of the Indian Freedom Struggle, with her husband’s backing.

She began working with the illiterate and joined the Charkha Class. She also had a significant impact on the Indian National Congress’s “Jan Jagaran” campaigns, which raised public awareness of social ills.

Sayani’s operations included the suburbs and the metropolis of Mumbai.

Syed Fakrul Hajiya Hassan (Died 1970)

Syed Fakrul Hajiyan Hassan, who not only took part in the Indian freedom fight but also urged her children to do so. She was born into a family that immigrated to India from Iraq. She raised her kids to be freedom fighters who later gained notoriety as the “Hyderabad Hassan Brothers.”

Hajiya wed Amir Hassan, who had relocated to Hyderabad from Uttar Pradesh.

She adopted Hyderabadi culture as a result. Amir Hassan, her spouse, had a senior position in the Hyderabad government. He was required to travel to several locations as part of his employment.

She noticed the suffering of women in India while on her visits. She put a lot of effort into the growth of female children.

She lived in Hyderabad, which was governed by the British, yet she actively engaged in the National Freedom Movement since she was a lady with strong national emotions.

She burned foreign clothing at her Abid Manzil in Hyderabad’s Troop Bazaar in response to the demand of the Mahatma Gandhi. She took part in the non-cooperation and Khilafat movements.

She regarded each soldier in the Indian National Army as one of her children. Along with Smt. Sarojini Naidu, and Fhakrul Hajiya put a lot of effort into getting the heroes of Azad Hind Fouz released.

source: http://www.siasat.com / The Siasat Daily / Home> Featured News / by Marziya Sharif / August 17th, 2022