Kolkata, WEST BENGAL :

Nawabi Calcutta: An overlooked era, organised by Know Your Neighbour and INTACH, highlights how Thumri, Kathak and Urdu blossomed under King of Oudh’s patronage.

Speaker Sabir Ahamed during the bicentenary celebration of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah | Picture: Know Your Neighbour

Kolkata:

We all remember the story of Wajid Ali Shah, the ruler of Oudh, being exiled to Kolkata by the East India Company for being a poor administrator. But how many of us know that the ruler had travelled to the colonial Kolkata with around 6000 attendants in 1856, in hope of travelling to London to place his case before Queen Victoria concerning the unfair annexation of his kingdom? How many of us are aware of the fact that it was only in 1857, when the first revolt for independence broke out that the recuperating Shah was kept under house arrest?

But the most intriguing aspect about the Shah’s stay in Kolkata was his ability to not lose hope, despite being robbed of his throne and his journey of recreating mini-Lucknow (Metiabruz) along the bank of river Hooghly. And little by little bringing the Lucknowi style to Bengal.

How the Shah took on to his new life, patronised art and rebuilt a mini-empire of his miles away the banks of Gomti was what Nawabi Calcutta: An overlooked era attempted to recall.

“There is more to Wajid Ali Shah and his ‘Chota Lucknow’. We shouldn’t just remember him for bringing biryani to Kolkata and giving it a spin by introducing potato to it,” said Sabir Ahamed, of Know Your Neighbour (KYN), during his inaugural speech.

The remains of structures built by Wajid Ali Shah, have often been overlooked by Kolkatans. Rare images of old Metiabruz and structures built by the last king of Oudh were screened during the programme. Ninety-nine per cent of these structures built by the Wajid Ali Shah, no longer exist, said Shaikh Sohail, who conducts heritage tours in Metiabruz. He gave a call to all to come and visit the remains and know the history of the Shah’s ‘Chota Lucknow.”

The invitation card of the event

Remembering the last king of Oudh, Sudipta Mitra, author of Pearl by the River ( a book that documents the life of Wajid Ali Shah) chose to highlight his love for rare animals. A connoisseur of wild animals, the Shah even created a mini zoo, which home some rare animals including an open snake house much ahead of Kolkata having a zoo of its own.

“His love to collect unique or rare wild animals for his personal zoo was so famed that zoologist Edward Blyth once wrote to his friend Charles Darwin about the King of Oudh and his love for animals. He wrote that till the Shah is alive, animal trade would flourish in India,” said Mitra.

He then went on to add, “Once Oudh was annexed, about 18 tigers from the Shah’s personal collection were brought by Blyth for Rs 20 each. These tigers were put on display for the public at the present age Teratti Bazar. And later when the Shah made Metiabruz his home, he brought three tigers from his pre-owned collection for his new personal zoo at a much higher price.”

In a bid to feel at home, the pining Shah, even established the famed Sibtainabad Imbara, where he now rests, much like his father Amjad Ali Shah, who rests at Hazratganj’s Sibtainabad Imbara.

Debunking the poor administrator theory was Dr Soumik Bhattacharjee. While addressing the audience, Dr Bhattacharjee said, “The East India Company (EIC) created a narrative to justify their annexation of Oudh. The Shah was a lover of art, and that’s not a crime. He promoted thumri, kathak and a lot of artists during his reign. He also introduced a number of administrative reforms, which were good for Oudh. But the ECI brought in laws that made it difficult for the king to do his work in a judicious way. The king, failing to understand the implications of the new laws, fell prey to ECI’s trap.”

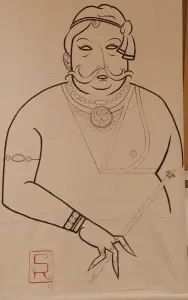

A portrait of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah at the event venue| Picture: Soumyadeep Roy

“While Prem Chand was almost reprimanding in his play Shatranj Ke Khiladi, Satyajit Ray was more understanding towards the king of Oudh. The king’s decision to not revolt against the British and approach Queen Victoria regarding the unfair annexation should be seen as his fondness for non-violence and not weakness,” he summed up.

Taking up from where Dr Bhattacharjee left, was foodpreneur and great great granddaughter of the Shah, Manzilat Fatima. “It’s sad that not many know about the history and reality of Wajid Ali Shah. My father, Dr Kaukab Quder Meerza, wrote a book on him in Urdu, which has been translated into English by sister Talat Fatima.” She added that they are also working on a project to highlight the revolutionary work of Begum Hazrat Mahal.

On being asked if the Indian historians have been a little harsh on the king of Oudh, she said, “It’s sad that the historians despite being Indians chose to highlight the narrative set by the British and East India Company. But it’s heartening to see so many remember Wajid Ali Shah with great fondness. I am humbled by the number of events that are being organised to mark his bicentenary. As his descendants, we will try doing our bit to keep his legacy alive.

While, Mohammad Reyaz, Assistant Professor, Aliah University, highlighted the central focus of the Nawab’s migration – rebuilding a new city, which was demolished after his death and the legacy that he created in the field of art. “The Nawab of Oudh was beyond bringing biryani to Kolkata,” he said.

The event organised by INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) and Know Your Neighbour, also hosted an art exhibition – Dastan-e-Akhtar by visual artist Soumyadeep Roy, who chose to pay tribute to the king through his paintings.

Also present at the event was Sarod maestro Irfan Md Khan, whose ancestor had travelled to Kolkata with Wajid Ali Shah. He summed up by saying, “The Shah was a patron of art. He patronised and promoted kathak, thumri and sarod to this city.”

source: http://www.enewsroom.in / eNewsRoom India / Home> Bengal> Inclusive India / by Shabina Akhtar / July 26th, 2023