ASSAM :

Ajmal Foundation’s Super 40 program started with a science topper in board exams (2018) and later prepared students for medical and engineering exams.

New Delhi:

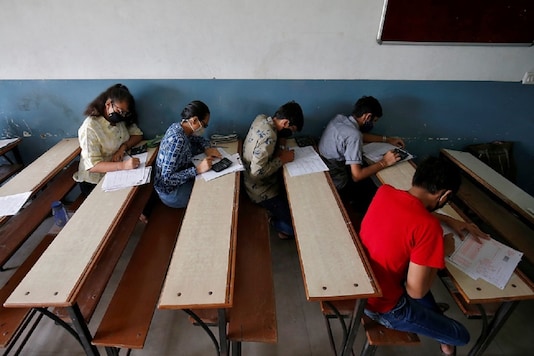

All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) President Badruddin Ajmal’s integrated educational program with a special focus on students from underprivileged background has fought against all odds to deliver great results in competitive exams such as NEET/ JEE(Main)/(Advance).

On Saturday the MP tweeted: “More than 100 students from our 2-years Integrated Coaching Programme have cleared NEET this year, of which 80+ students likely to get admission in MBBS. My heartfelt thanks to the faculty and other staff members associated with Ajmal Super 40 programme and Ajmal Group of Colleges (sic).”

Badruddin Ajmal was referring to the Ajmal Foundation’s Super 40 program that started with a science topper in board exams (2018) and later prepared students for medical and engineering exams. Eleven students cleared NEET (2019), and more than 100 students cleared NEET in 2020 with 80-plus getting admissions in MBBS.

According to the director of Ajmal Foundation, Khasrul Islam, from 11 students clearing the exam in 2019 to over 80 likely to get admission in MBBS this time, “the result over the year is speaking for itself on how commitment and dedication of teachers and students can make all the difference.”

This year in JEE (Advanced) and (Mains) there were 7 and 18 students clearing the exams, respectively.

The students’ response to Super 40 has been overwhelming over the years. “After seeing the keenness among them to study for medical and engineering, the Foundation increased the sponsored participants from 40 to 160 (80 girls and 80 boys),” he said.

Islam said the key feature of the integrated program is its teachers with most of them being non-Muslims. “About 75% of the teachers are non-Muslims and their dedication is the life of the program. They are committed and available to clear all doubts of the students, who are majorly Muslims, almost 75%”, said Islam.

The Ajmal Foundation is a registered public charitable trust, established in the year 2005 at Hojai, Assam, India. It has 25 educational institutions all over the state of Assam. “The organisation has been working in the fields of modern education, skill development and employment generation, women empowerment, poverty alleviation, relief and rehabilitation, and environmental awareness and health aid programs,” states its official website.

The trustees of the foundation are committed to undertake multifarious schemes and projects in various parts of the country to “serve the downtrodden section of the society.”

source: http://www.news18.com / News18 / Home> News18> India / by Eram Agha / October 18th, 2020