INDIA :

A new biography looks into Akbar’s life to draw some inspiration on how to manage the boardroom. The third Mughal emperor was always thinking on his feet, one step ahead of friend and foe; but he also knew that force had to be tempered with tolerance, and confidence with caution.

Akbar’s Tomb in Sikandra, Agra | Photo Credit: cinoby

Even as elements in the right-wing have made attempts to nibble at the great Jalaluddin Akbar, historians and authors have taken it upon themselves to project the third Mughal emperor clothed in nothing but facts of history.

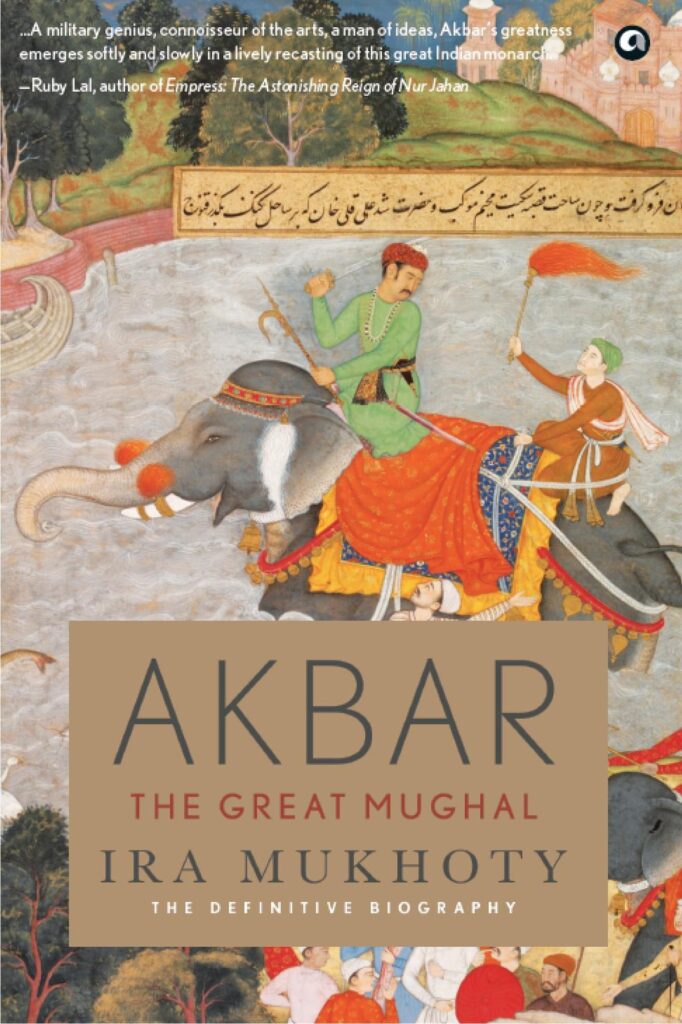

Around the time of COVID-19, Ira Mukhoty came out with her exhaustive biography, Akbar The Great Mughal: The Definitive Biography (Aleph). It came on the heels of Manimugdha S. Sharma’s Allahu Akbar: Understanding the Great Mughal in Today’s India (Bloomsbury) where the author, as the title suggests, made an attempt to see the Mughal monarch in the light of modern-day developments.

The books show why Akbar is considered an Indian icon and a king with compassion and empathy. Instead of spending his childhood as a royal prince, practising calligraphy and honing his skills with the sword, Akbar lived those years, as Mukhoty writes, “in the company of his beloved animals and their keepers…He raced pigeons, ran alongside camels and dogs, and hunted cheetahs, lions, tiger, and deer. And Akbar tested his physical strength and courage against wild elephants, learning to ride and to tame them.”

Akbar had grown up practically illiterate but would eventually be “known for his reverence for learning, penmanship, books…and would patronise some of the most extraordinary works of writing, translation and illustration ever undertaken in the country,” Mukhoty points out.

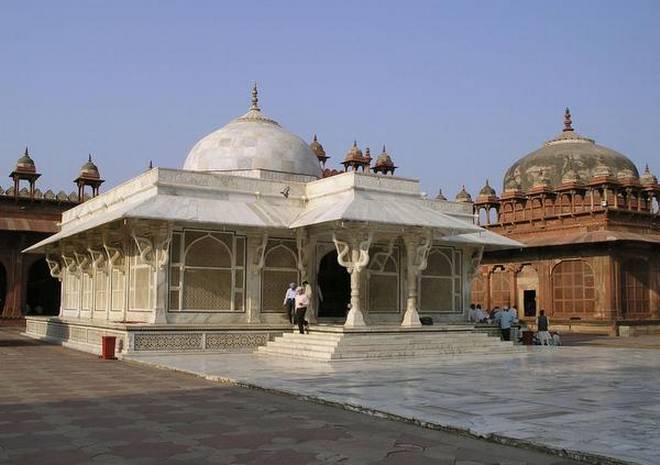

This quest for knowing the unknown led Akbar to build Ibadat Khana, an assembly of scholars of different religions. Akbar’s congregation of men of spiritual accomplishment was the work of a truly liberal mind. At a time when the Safavids were persecuting non-Shias in Iran and Europe had no space for non-Christians, Akbar invited them all. He abolished the religious tax, jiziya, for non-Muslims and did away with the pilgrimage tax on Hindus and was known to prevent Sati. As Sharma quotes Abul Fazl in Allahu Akbar, “The Shahenshah in his wisdom and tolerance remitted all these taxes, which amounted to crores. He looked upon such grasping of property as blameable and issued orders forbidding the levy thereof.”

In simpler words, it meant, as Sharma writes, “The state wouldn’t come in between an individual and his faith.”

Beyond religion

Yet Akbar’s relevance goes beyond the sphere of religion as noted journalist and author Shazi Zaman discusses in his latest, Akbar The Great CEO: The Emperor’s 30 Rules of Leadership. Published by Speaking Tiger, the book has a contemporary, and non-historic feel to it. In its innovative approach lies its appeal. Zaman presents Akbar as a practitioner of some dictates which would do a management guru proud. Interestingly, the book opens with the words of a Jesuit priest stationed at Akbar’s court. The priest wrote in awe, “He was a prince beloved of all, firm with the great, kind to those of low estate, and just to all men, high or low, neighbour or stranger, Christian, Saracen or Gentile; so that every man believed that the King was on his side.” The priest’s words were borne by the fact that Akbar, as Zaman writes, “perfected the art of ruling with a light touch even though he had the means to be brutal.”

The surprise factor

So what were the 30 rules of Akbar? Though he ruled in an age when the Emperor was often larger than life, Akbar believed in subtlety. Importantly, as his experience with the Afghan king Daud Khan Karrani proved, Akbar was not just fast in his thinking, he was unpredictable too. When he would be least expected to show up in a battle, he would take the enemy by surprise, vanquish his forces, and bring him to his knees. “When the Rubicon was to be crossed was a call that he [Akbar] took in a manner so unpredictable that his opponents could never gain an advantage by guessing it,” writes Zaman. “The Emperor’s audacity was well documented visually as well… In one painting, he is seen holding a cheetah by its ear, and in another painting, he is seen mounted on a mast elephant and chasing another across a shaky bridge built on boats.”

Zaman mentions another incident which underscores Akbar’s acuity. When a slave attacked him, Akbar knew who was behind it but chose to remain quiet.

As Zaman writes, “Even the truth has to await its moment.” Does it remind you of office boardroom meetings? Maybe. But remember this was the strategy of the Mughal emperor who was merely 21 at the time of the attack. He knew the truth, but also knew how to use it to his advantage later in life.

Little wonder then that one of Akbar’s favourite books which he also recommended to his officers was Akhlaq-i-Nasiri, a 13th century text on etiquette and way of life, which said, “The king should keep his secrets concealed, so that he can change his mind without sounding contradictory…The need to keep secrets has to be combined with the need to consult intelligent people.” Akbar did it all.

Be it his relationship with Maham Angaand Bairam Khan, or later the Rajputs, Akbar was always smart and wise.

Zaman’s book progresses like an equation in a science book as he goes on to reveal many facets of Akbar’s personality.

Cultivated image

One such aspect was the way he looked, and the way he presented himself. “Akbar’s image was cultivated, recorded and disseminated with a lot of thought. There was a message in how he dressed and looked and what he chose to be doing in the picture. Each portrait portrays a facet of his personality. It never was a picture for the sake of a picture,” writes Zaman.

Written with the brush of an artist, the book is a must-read for anyone looking for life lessons and critical values, particularly in the boardroom. The ‘illiterate’ emperor was indeed a wise man, who never “went to extremes” in any direction.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books / by Zia Us Salam / December 25th, 2025