Bengaluru, KARNATAKA / Kolkata, WEST BENGAL :

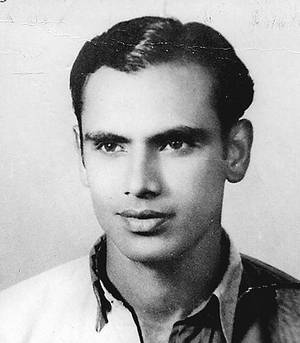

As Ahmed Khan is laid to rest, kin feel blessed to belong to the same family as the football great; contemporaries remember him as a humble man who loved the game

Amjad Khan sat quietly sipping chai, unmindful of the cacophony raised by a line of four-wheelers jostling for space on the narrow, single-laned Mackan Road. His brother Ahmed, arguably India’s greatest footballer who passed away on Sunday, had just been laid to rest and the mourning — for now — was over. The multitude, that had turned out to pay their respects and attend the funeral, had departed and house #75 — the house of ‘Ahmed, the Olympian’ — was slowly returning to ‘normal’.

A smile spread across Amjad’s face when he was asked about his brother. With every sip of chai that he took, Amjad’s eyes took on an even more vacant look as his mind went back in time. “What makes a man great? This is how I analyse it,” Amjad, also a former India international, said. “You could say Ahmed played up to 1958, right? Public memory is generally short. We watch a good movie and don’t remember it a month later. But if people remember this man, after 60 years of his playing career, then he must have done something extraordinary.”

There was pride in Amjad’s every breath. It was the predominant feeling shared by those in house #75. A feeling that stemmed from simply being associated with the bloodline of India’s greatest dribbler, fondly nicknamed ‘the Snake Charmer’ by the English media. Even Mannan, a grandson who was born decades after Ahmed hung up his boots, said he was “proud to just be born in the same family as Ahmed”.

Inside the house, Mannan proudly pointed to Ahmed’s trophies, a collection that was put on display just above the freezer box that contained Ahmed’s remains only hours ago. Numerous tributes by East Bengal, Ahmed’s club in Kolkata, were laid out. “The Padmashri has lost a bit of its sheen today because it was never awarded to Ahmed,” Amjad remarked on the conspicuous lapse of the Central government’s attention to a man who had bagged the gold in the 1951 Asian Games.

Among India’s greatest football heroes, Ahmed is right up there. As an inside-left (withdraw striker), Ahmed played in two Olympics (1948 and 1952) and won every domestic trophy that was up for grabs with East Bengal. “You know the thing about cotton? Whatever you throw on cotton, it never bounces back. That was Ahmed’s dribbling prowess,” Amjad said. “My father used to say that if Ahmed had not become a footballer, he would have become India’s best athlete. You know, when he was studying in the St Aloysius School in the city, he never used to carry books to the school. Instead, he used to take a small ball, a tennis ball, and practise dribbling on his way to school and back. That explains his gift.”

Ahmed was part of the deadly ‘Panchapandavas’ of EB, a forward line also comprising P Venkatesh and PB Saleh on the flanks, Apparao as the inside right and Dhanraj in the centre. When asked whether the gold medal was Ahmed’s top moment as a player, Amjad laughed. “That was just okay,” he said. “Have you heard of Sahu Mewalal, the guy who scored the winner at the 1951 Asian Games? Every year in Calcutta, where he used to play for Railways, he was the top-scorer of the league. Dhanraj wanted to overthrow Mewalal and asked Ahmed to do something for him. In one game, this gentleman (Ahmed) dribbled past everyone, even the goalkeeper, and called Dhanraj to the post to tap it in. That year, Dhanraj became the top-scorer. Scoring goals was Ahmed’s wish when he was playing.”

I Arumainayagam, the 1962 Asian Games gold medallist from the other time that India ruled globally, called Ahmed an inspiration. “We used to learn from watching him play,” he said. “We used to name ourselves ‘Ahmed’, ‘Dhanraj’, ‘Basheer’ and emulate their style. We, of course, couldn’t play as well as they did, but they influenced us greatly.”

More than anything, Ahmed was a fine human being. The 1952 Helsinki Olympics showed that. India were humiliated 1-10 by Yugoslavia and Ahmed repents that he was able to score only one goal in that game. Outside the Olympics, he often used to skip practice sessions while playing for East Bengal which made people wonder at his talent. He also preferred to play barefoot, shunning boots when the occasion afforded it. He was also fond of playing cards and often drew players from rival club Mohun Bagan into a round after a football game. During one such game, he was up against Sailen Manna, Bagan’s top defender of that era. “Manna was trying to convince Ahmed to play for Bagan,” SS Shreekumar, a former journalist and Ahmed’s friend, said. “This was in a room packed with footballers from Bagan and their supporters who were watching them. Eventuall, Ahmed agreed to play for Bagan. The entire room was stunned on hearing it. But Ahmed had one condition.

Manna asked him what it was. He told Manna that he will have to play for EB and the room burst into laughter.”

Shreekumar wonders what could have been had Ahmed accepted an offer to play for Swedish club IFK Göteborg. “He was named East Bengal’s best forward of the millennium,” Shreekumar said. “But when IFK Göteborg contacted Ahmed, his father asked him to consult his club, East Bengal. Jyotish Chandra Guha, a former secretary of EB who had scouted Ahmed, was worried about losing him. He downplayed Ahmed’s future in Sweden by suggesting it would be too cold and that the locals might put him down because he would be the only Indian there.”

While the tributes kept pouring in, Amjad’s tea was done. But the smile remained. “There are two things which makes football interesting – scoring goals and dribbling,” he added. “Ahmed found it interesting because of the second reason.”

Today, Ahmed Khan is no more. But ‘Ahmed Khan Olympian’ will live on forever.

source: http://www.bangaloremirror.indiatimes.com / Bangalore Mirror / Home> Sports> Football / by Aravind Suchindran, Bangalore MIrror Bureau / August 29th, 2017