Annigeri Village(Dharwad ), KARNATAKA :

Abdul Khadar Nadakattin from Dharwad in Karnataka has 24 innovations under his belt.

The niche but problem-solving machines and innovations help farmers with everyday solutions and have also increased their yield up to 25 per cent.

Splashing water on a deep sleeper to wake them up is a clichéd scenario used in many comedy films and on social media. But Abdul Khadar Nadakattin earnestly practised this comedy routine on himself during his school days to wake up early.

A native of the Annigeri village of Dharwad district in Karnataka, Abdul struggled to push himself out of bed in the mornings. “A splash of water on my face was the only solution to wake me up. But I could not expect my parents to do this to me every day,” he tells The Better India.

A then 14-year-old Abdul devised an innovative Wa(h!)ter Alarm. Its functioning was simple — one end of a string was tied to the key of his alarm clock in a manner that when it rang, the thread would unwind itself and the other end was tied to a water bottle. Once the alarm key unwound, the bottle would tilt, and the water would fall on Abdul’s face.

“It helped me wake up and complete my school,” he recalls, laughing. Though he managed to pursue education until Class 10, he did not pursue higher studies.

Abdul at his tamarind plantation

But his water alarm talks led to him speaking of the more serious water issues his village faced. “My father owned 60-acre ancestral land and the water scarcity deterred us from earning good profits from farming. My father admitted that our family’s financial condition was poor and asked me to contribute to the farm. So, I gave up my dream to pursue graduation in agriculture,” the 70-year-old says.

Being deprived of an education did not deter him from thinking out of the box. Little did he know then that the water alarm was the first of many of his innovations .

This farmer has come up with unique ideas to solve everyday farmer problems. To date, Abdul has had 24 innovations under his belt, which benefit thousands of farmers in India. It was for this reason that he won the Padma Shri award in 2022.

Helping Farmers, One Innovation At A Time

“Thomas Alva Edison is the source of my inspiration,” says the scientist who went barefoot to receive the President’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015 at the hands of the then President of India, Pranab Mukherjee. “I always thought of unique ways to solve a problem. That is how I conceived the water alarm. In 1974, I received the ancestral land from my father to continue farming. But interacting with fellow farmers and practising the occupation myself, I learned about the issues of finding labour and other difficulties faced in agriculture.”

Soon after taking over the reins, he built a tiller machine capable of deep ploughing which needed operating by a bullock. “In 1975, I established Vishwashanthi Agricultural Research and Industrial Research Centre to sell the product. But financial constraints did not allow me to market it well, and it failed to take off,” he says.

Later, he also built a plough blade that did not require sharpening and lasted for a long duration compared to others in the market. “The blade did not lose its sharpness, which ensured its long life. It could be attached to a tractor as well,” Abdul adds.

Following this, he built a seed-cum-fertiliser drill that enabled sowing seeds of different sizes with equal spacing. “The equipment is used in sowing a wide variety of seeds from jowar to groundnut. The device also facilitated the dispersal of fertilisers, soil and other organic matter,” he says.

To meet the demands of farmers in Maharashtra, Abdul constructed an automated sugarcane sowing machine. Slowly, his innovations became popular and saw an increase in demand.

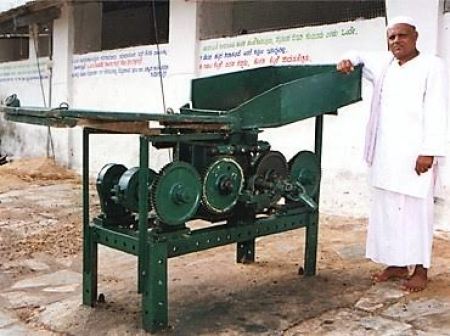

Abdul’s 5-in-1 tiller machine

Apart from his innovative pursuit of helping farmers, Abdul also worked to improve the agricultural yield on his farm.

As his father and grandfather suffered losses with erratic rains and limited groundwater reserves, Abdul decided to find an alternative. “In the early 1980s, I planted mango saplings, placed between ber and sapota (chikoo) trees. I planted chillies as an intercrop. But the lack of water killed the plantations. So I switched to growing tamarind as I learned that it required less water and maintenance,” he says.

He sourced 600 saplings and planted them across 6 acres of land by keeping a gap of 20 feet each.

In 1985, the region faced severe droughts, but Abdul managed to source water from a distance of 3 km. “I dug 11 bore wells, but only two yielded water. So I sourced water from a long distance and stored it by creating six farm ponds. They also helped to harvest rainwater during the monsoons. I used the water for flood irrigation of my plantation of 600 saplings,” he says.

“The plants grew well, and feeling confident with its success, I planted more than 1,100 trees in a 10-acre area, making a total of 1,800 saplings,” he says.

But there was another unexpected chapped Abdul faced. “I did not know how to make use of so much tamarind produce. My wife and daughter made pickles and jams to sell in the markets across the state including, neighbouring Hyderabad,” he says.

So, Abdul decided to harvest tamarind and make pickles out of them. “But the process of separating seeds from the tamarind was tedious, and labour shortage made it more difficult. The seeds had to be separated manually and were a time-consuming process,” he explains, building up the crescendo before revealing his next innovation.

After spending nearly Rs 3 lakh and over six months, Abdul conceived a machine that did the job. “The instrument involved a system where the tamarind slid on the tapered peg. This pushed the seeds out from the tamarind pod,” he says, adding that to make tamarind pickles convenient he built yet another device.

“The pickle making required tamarind to be sliced into smaller chunks which again was labour intensive. So, I designed another machine to make the slicing effective and efficient,” Abdul adds.

Over the years, Abdul produced more machines and sold them. His popularity with these niche but problem-solving innovations earned him the name ‘hunase huccha’, meaning ‘tamarind crazy’.

“It was the most difficult innovation of my life as the seeds often got stuck in the tamarind making the separation difficult. I researched and experimented for years to achieve the desired result,” he says.

An Innovation Revolution

Abdul receiving lifetime achievement award at the hands of then President Pranab Mukherji

Abdul has sold thousands of his various innovations to date, he claims with pride.

Shrikanth Jain, one of the farmers who purchased Nadakattin seed-cum-fertilizer drill a few years ago, says, “I used it to sow wheat pulses and other woodgrains. The machine does the job of sowing, dispersing fertiliser, covering the soil, spraying pesticides and saving fuel. It also helps to prevent excess sowing of seeds. Using the device has helped me increase my yield by 20 per cent.”

However, these innovations and his passion for helping the farming fraternity came at a heavy financial loss to Abdul who says, “I struggled with debts all my life and mortgaged part of my agricultural land to invest in research for innovations. I never sell equipment for profits and offer them at make-to-cost, which is about 25 per cent cheaper than the ones in the market. It is a seva (service) for the farmers, and I do not wish to burden them financially.”

Today, Abdul has received funding for his research from the National Innovation Foundation, University of Agricultural Sciences, Dharwad and Karnataka government. He adds, “I received Rs 16 lakh to develop the ploughing machine from the Karnataka government and have also invested other prize money received.”

Elaborating on his innovative process, he says that some innovations happen in months while others take a year or more. “Investing time and money can become very demanding.” But Abdul is relentless and wants to continue his dream of helping farmers. “I believe that the economy of this country runs on farmers. But our community is facing hardships at various levels. I aim to benefit them and ease their difficulty. Innovations can only bring the next revolution in agriculture,” he says.

source: http://www.thebetterindia.com / The Better India / Home> Stories> Innovation> Karnataka / by Himanshu Nitnaware (headline edited) / Edited by Yoshita Rao / February 05th, 2022