BRITISH INDIA :

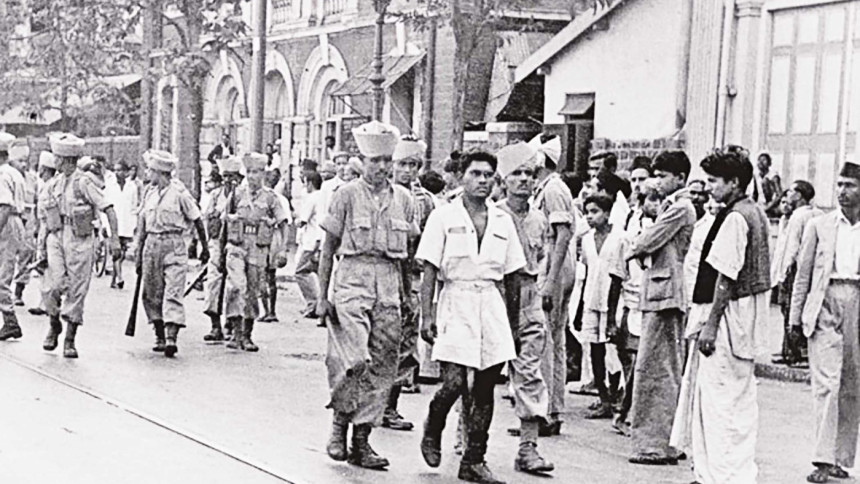

After the Second World War, soldiers of the Azad Hind Fauj (Indian National Army) were captured by the British forces. They were charged with treason and tried by tribunals as war criminals. Indians protested against this treatment given to the freedom fighters of Azad Hind Fauj.

In February, 1945, soldiers and officers of the Royal Indian Navy mutinied in Mumbai and Karachi. English officials including the Viceroy took this mutiny as a sign of leaving India. The British forces killed many to quell the mutiny, many of which were Muslims.

Here, we are sharing names of the few Muslims we know, who attained martyrdom for taking part in the mutiny or supporting it.

Abdul, Ali, Din Mohammad: born 1929, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Nagpada, Bombay, on 23 February 1946, died the same day.

Abdul Aziz: born 1921, domestic servant, hit by bullet in the premises of his employers as a result of firing by the police at Bombay on people demonstrating in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Abdul Razak: born 1916, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound on 22 February 1946 in firing by the police near Crawford market, Bombay, died on 24.2.46.

Abdul Rehman: born 1911, employee of private firm, hit by a bullet as a result of firing by the police at Doctor’s Street, Bombay, on people demonstrating in support of the revolt by rating of the Royal Indian Navy on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Abdul Gani: born 1901, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by police at Bombay on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Abdul Karim: born 1926, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near Crawford Market, Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Abdul Sattar, Mohmmad Umar: born 1924, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police on 22 February 1946 at Bombay, died the same day.

Abdulla, Abdul Kadar: born 1921, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bern- bay on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Abdulla, Safi: born 1933, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound on 22 February 1946 in firing by the police at Fort, Bombay, died in hospital the same day.

Adamji, Mohamed Hussain: born 1924, son of Allauddin Adamji, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound on 22 February 1946, in firing by the police at Bombay, died in hospital.

Ali Mohammad: born 1906, hit by bullet in firing by the police at Dadar, Bombay, on people demonstrating in favour of the revolt by ratings of the RIN on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Anwar Hossain: a student of Lahore College, hoisted the flags of revolt in the rating vessel Bahadur in Karachi, died with flags in hand on 23 February 1946.

Asgar Ismail: born 1934, received a bullet wound in firing by the police on people demonstrating in support of the revolt by ratings of the Hoyal Indian Navy on 23 February 1946, near the Paxsi Statue, at Byculla, Bombay, died on the spot.

Asghar Miya, Nawsati: born 1916, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near the J. J. Hospital, Bombay, on 23 February 1946, died in hospital.

Aziz, Chhotu: born 1921, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bombay on 23 February 1946, died in hospital the same day.

Dilawar, Abdul Malik: born 1931, son of Dilawar Muzawar, student, hit by bullet in firing by the police at Dongri, Bombay, on people demonstrating in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Fida Ali, Kayam Ali: born 1933, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near J. J. Hospital, Bombay, on people demonstrating in favour of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 23 February 1946, died the same day.

Gulam Hussain, Ali Mohammad: born 1906, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police’ at Bombay on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Haroon, Hamid: born 1931, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bombay, on 23 February 1946, died the same day.

Ibrahimji, Yusufali: born 1910, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bombay on people’s demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Ismail Hussain: born 1932, hit by bullet as a result of firing by the police at Bombay on people demonstrating in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 22 February 1946.

Ismail, Rahimtulla: bom 1911, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near the Imperial Bank, Abdul Rehman Street, Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Jamal Mohammed: born 1926, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bombay on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Khuda Bakhsh, Pyare: born 1876, hit by bullet as a result of firing by the police at Bombay on people demonstrating in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 23 February 1946, died the same day.

Manzoor Ahmed: born 1906, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound; in firing by the police at Bombay on 22 February 1946, died in hospital the same day.

Mohammed, Aboobakar: born 1928, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the RIN, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near Crawford Market, Bombay on 22 February 1946, died in hospital the same day.

Mohammed Aziz: born 1911, took part in the popular demonstra- lions in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bombay on 22 February 1946, died in hospital the same day.

Mohammed Hussain: born 1931, son of Mulla Gulam Ali Abdul Hussain, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near J. J. Hospital, Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Mohammed Sheik, Sayed Hassan: born 1921, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near Null Bazar police station, Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Mohiddin, Sheik Ghulam: born 1928, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Parel, Bombay, on 22 February 1916, died the same day.

Mohmed Samikh, Taja-Urkh: born 1920, hit by bullet as a result of firing by the police at Kamathipura, Bombay, on people’s demonstration in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 23 February 1946, died the same day.

Moula Bakhsh, Abdul Aziz: born 1906, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Kamathipura, Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Siddik Mohamed: born 1921, son of Isak Mohamed, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Kamathipura, Bombay, on 23 February 1946, died the same day.

Sulemanji, Zakiuddin: took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police at Bombay on 22 February 1946, died in the hospital the same day.

Taj Mohamed, Fazal Mohamed: born 1930, took part in the popular demonstrations in support of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near the Salvation Army office at Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

Vazir, Mohamed: born 1891, took part in the popular demonstrations in favour of the revolt by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy, received a bullet wound in firing by the police near Hindmata Cinema, Bombay, on 22 February 1946, died the same day.

source: http://www.heritagetimes.in / Heritage Times / Home> Featured Posts> Freedom Movements / by Mahino Fatima / August 14th, 2021