Shahbad District / Patna, BIHAR :

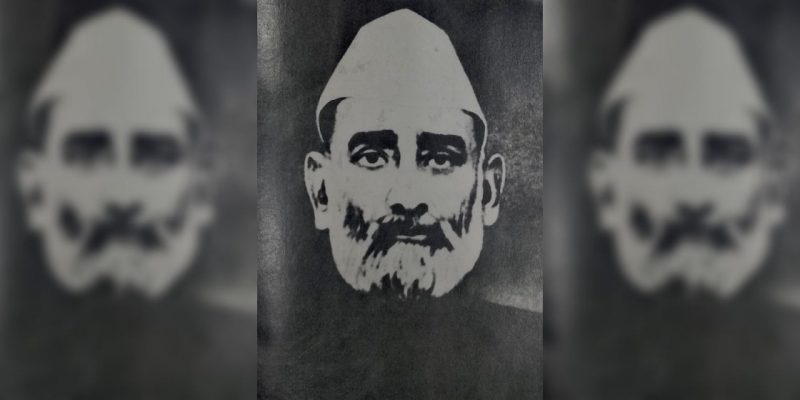

This May Day, remembering Abdul Bari.

Abdul Bari is not a name that many Indians remember, but Munawwar, a committee member of the Tata Motor Workers’ Union in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, holds the name in high esteem.

“I don’t see a leader like Abdul Bari [coming up] in the near future,” he said. “It is because of his efforts that we still get high tea at just six paisa.”

“Once, Bari went to the Tatas and he was offered tea. He asked them to first offer it to the workers, and then made an agreement which is still benefitting us. Upma, aloo chaap, samosa all for six paisa in the company’s canteens.”

Asked how they pay six paisa when currency that small no longer exists, he says, “We get token of Rs 2 or more and keep using it for weeks.”

Munawwar visits Bari’s grave every year on March 28, the death anniversary of the pre-independence labour leader, to offer flowers. This duty, he says, was assigned to him by the Tatas.

Thinking of labour in the days of capital

Despite the large numbers of workers who struggle to earn a square meal a day, major political parties remain hostile towards them. In the 55-page Congress manifesto, the words ‘worker’ or ‘workers’ appear 15 times; in the BJP’s 45-page manifesto, the words appears only five times – four while referring to Asha and anganwadi workers. ‘Labour’ figures 21 times in the Congress manifesto, and only twice in the BJP’s.

The Congress does talk about ending the workers’ exploitation and improving working conditions. The party’s manifesto details new schemes and promises to implement old ones related to organised, unorganised and contractual labour. But it is anyone’s guess how schemes that have been on hold for so long will suddenly spring to life.

Dilip Simeon, a founding member of the Association of Indian Labour Historians and former professor of history at Ramjas College, says that nobody talks about labour now because “in today’s context, the labour movement is influenced by communal sentiments”.

“If labour is with the BMS [Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh] and Shiv Sena, then this is the weakness of the movement; if the labour movement wants to regain its power, then it has to face this challenge.”

Before independence, Simeon says, regardless of community, “leaders came together to advance the struggle of workers in India. Abdul Bari, Maneck Homi and Hazara Singh were their leaders. A Muslim, a Parsi and a Sikh could all be leaders of a workers’ movement.”

“Abdul Bari was so trusted that workers would start their protest first and then ask –what’s our demand?”

Bari was born in 1882, in Bihar’s Shahabad district. He was a student at Patna University in 1919 and was later appointed as a professor of history there, before he started studying law.

He quit to join the Khilafat movement, and actively participated in Gandhi’s civil disobedience movement and salt satyagraha. Bari did not restrict himself to the cause of one social group; he supported several political parties, including the Socialist Party and Swaraj Party, in parallel with the Congress. In addition, he was the voice of the labour movement in India and president of the Jamshedpur Tata Workers’ Union.

What Gandhi said about Bari

The journalist Afroz Alam Sahil has written a book on Abdul Bari, Professor Abdul Bari: Azaadi ki Ladaai Ka Ek Krantikaari Yodhha (Professor Abdul Bari: A Revolutionary Warrior of the Freedom Struggle). The author reveals several stories which won’t be found Indian history books. One such story is around Bari’s mysterious murder, and Gandhi’s reaction to it.

According to a report published by the Times of India on March 31, 1947, Bari was shot dead in the evening of March 28 while on his way home from Khushrupur, 24 miles from Patna. He was then the president of the Bihar Provincial Congress Committee. Following his death, a complete strike was observed, and Tata closed all its plants except essential ones.

Gandhi, in a speech on March 29, 1947, mentioned that he was struck by Bari’s simplicity and honesty. Gandhi added that he was planning to be more closely associated with Bari, and make an appeal to keep his short temper in check as it was not befitting of the highest office in Bihar. Gandhi referred to Bari in the same speech as “a very brave man with the heart of a fakir”. He declared that Bari’s death was the result of an altercation that had ensued between Bari and one Gurkha member of the anti-smuggling force, who was a former member of the Indian National Army.

The author mentions in this book that Bihar’s first Prime Minister (Premium) Barrister Muhammad Yunus had disclosed in an interview to the Orient Press of India that Bari had threatened to disclose the names of some prominent Congress leaders who were involved in the Bihar carnage – just three days before he was killed.

Yunus also said that Gandhi’s statement was given in haste. In his speech, Gandhi had told the audience that there was no politics of any kind in the death, and that it would be unjustified to associate the whole Indian National Army with Bari’s killing just because of one man’s actions.

In another incident discussed in the book, Gandhi arrives at Fatuaha station near Patna in the early morning of March 5, 1947. He travelled from Calcutta to Patna. Bari, chief minister Srikrishna Sinha and others welcomed him on the platform. As soon as Gandhi saw Bari, he laughed and said, “How is it that you are still alive?”

“This book is an attempt at bringing back his identity not just as a leader of the labour movement but a prominent leader of the freedom struggle of India,” the author says. “Professor Bari was one of the biggest leaders of the labour struggle in India. But limiting his role to even that would be unjust, because he was present in every chapter of the independence movement….The speciality of Abdul Bari is that he questioned his own party Congress when it came to the rights of workers.”

In a speech, Bari said, “We are in Congress to serve the poor of this country not to respect Gandhi, Rajendra Babu and Shri Krishna Babu…Lakhs of Indians who walk with them are not there to make them kings but to achieve freedom for this country.”

According to Sahil, “He criticised Gandhi and Rajendra Prasad many times because he was wholeheartedly committed to this struggle. He wanted to organise an all India conference for workers. He had formed the All India Mazdoor Sevak Sangh. He mentioned this in a letter written by him to Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel on 22 June 1946.”

Why commemorate leaders like Bari today? Sahil has the answer. “Today when Muslim youth talk about Muslim representation, they must read more about Bari, the symbol of Hindu-Muslim unity, in order to understand their own political history and determine how it influences their future.”

Afshan Khan is a Delhi-based freelance journalist.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Analysis> Labour / by Afshan Syed (headline edited) / May 01st, 2019