SINGAPORE :

On August 4, 1914, the British Empire declared war on Germany, making WWI a truly global war. As Britain observes the centenary of the war on Monday, TOI takes a look at one episode of 1915 that rattled Britain and her empire.

On February 15, 1915, the 5th Light Infantry Regiment of the Indian Army was getting ready to embark on a voyage to Hong Kong from Singapore. A little after 3pm, one sepoy Ismail Khan of C company fired at an ammunition lorry from the quarter guard near Alexandra Barracks. Soon, sepoys and VCOs (viceroy’s commissioned officers) of four predominantly Muslim Rajput companies (there were some Jats and Lohias too from Haryana and Punjab) of the eight-company strong regiment mutinied, starting a week of chaos and bloodshed that has come to be known in history as the Singapore Mutiny.

A lot has been written about the mutiny ever since, but very few have been works of scholarship. Fewer still are the official histories of the event. But in India, there’s a great deal of mystique surrounding this episode, which nationalists, historians and others, have linked to the freedom movement. They see some commonality between the 1857 Uprising and this one, and glorify this mutiny, without, of course, considering what the main actors of the event, the rebel sepoys, said in their testimonies to the courts of inquiry.

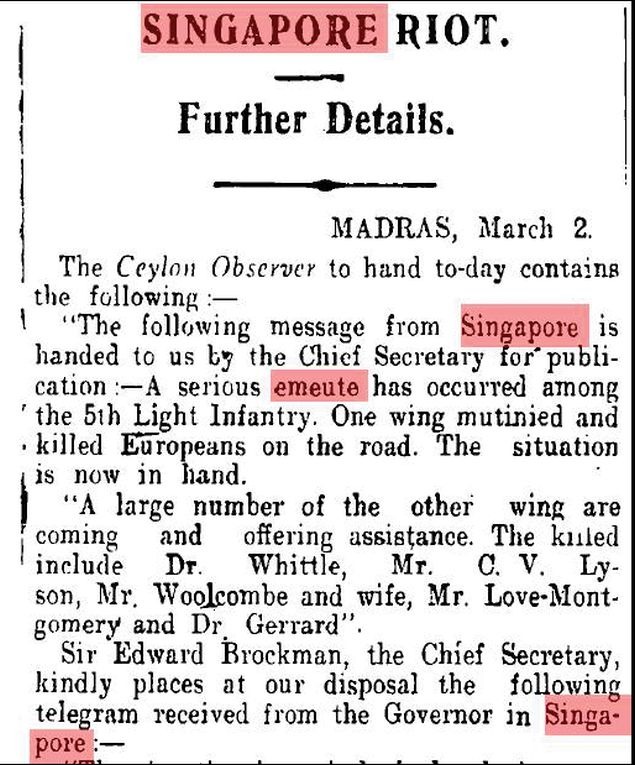

Snapshot of a TOI article from 1915 on the Singapore Mutiny

They gave ambivalent statements, turned coats, played victims, and testified against men already dead in the mutiny or executed by firing squads. They did all this to exonerate themselves and men of their own caste/village from swift colonial justice. Even those sepoys who were identified as mutineers by others spun convincing tales to fool the court.

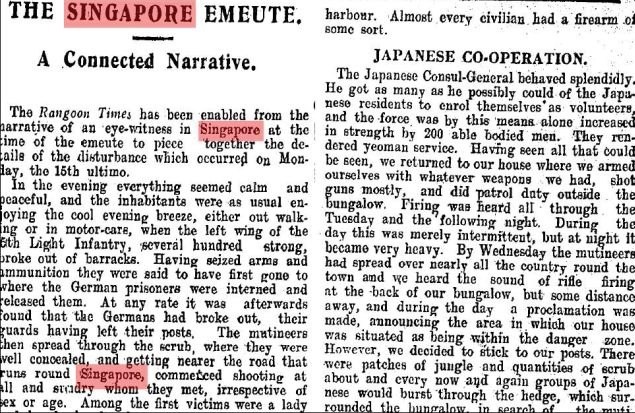

The Times of India had extensively reported the mutiny in 1915, calling it the Singapore Emeute. On March 2 that year, when the mutiny had already been put down and the inquiry was on, the first news of the mutiny had reached India. This paper had reported then: “A serious emeute has occurred among the 5th Light Infantry. One wing mutinied and killed Europeans on the road. The situation is now in hand. A large number of the other wing are coming and offering assistance.”

The mutineers belonged to the right wing of the regiment. The left was primarily composed of Pathans (the sepoys, though, called themselves Hindustani Pathans) who also came from the same regions as the Muslim Rajputs—Punjab and Haryana, including areas that form part of Delhi NCR today. These men didn’t join the mutineers, but ran helter-skelter in the melee and shut themselves in bathrooms/toilets and shops, with many escaping to the forest.

It was a deja vu moment for the regiment, which, in its previous avatar as the 42nd Bengal Native Infantry regiment, had seen exactly four companies rebel during the 1857 Uprising and the rest staying loyal. That was the reason why the regiment wasn’t disbanded after the Uprising was quelled. In 1915, too, the regiment would escape disbandment because of this reason, and would “honourably discharge its duty and salvage its lost reputation” in East Africa where they would fight the Germans.

But in the week that the mutiny lasted, the rebels killed 12 British officers and 14 European civilians, liberated German prisoners held in a jail (of whom 17 joined them and the rest stayed neutral), and got on board by persuasion or intimidation some men of the Malay States Guides.

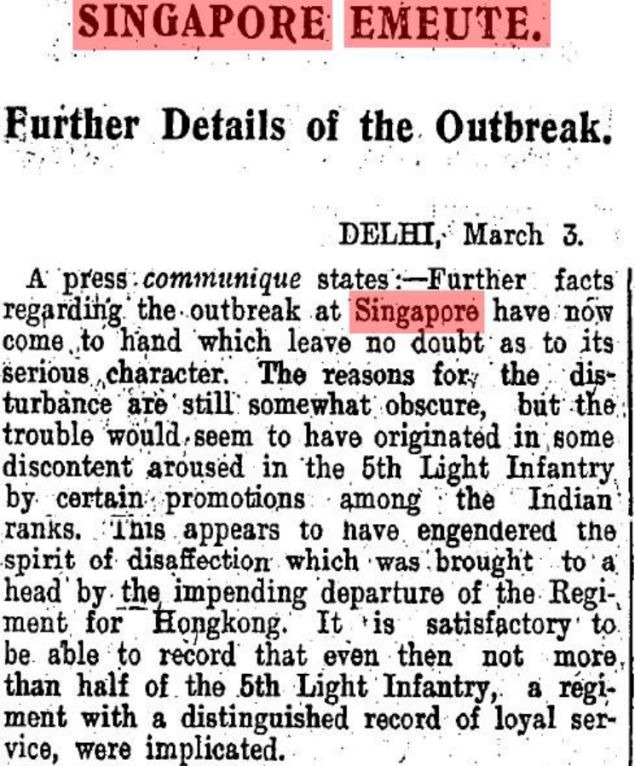

On March 3, 1915, The Times of India had a clearer picture of the mutiny. “Further facts regarding the outbreak at Singapore have now come to hand which leave no doubt as to its serious character. The reasons for the disturbance are still somewhat obscure, but the trouble would seem to have originated in some discontent aroused in the 5th Light Infantry by certain promotions among the Indian ranks. This appears to have engendered the spirit of disaffection which was brought to a head by the impending departure of the regiment for Hong Kong. It is satisfactory to be able to record that even not more than half of the 5th Light Infantry, a regiment with a distinguished record of loyal service, were implicated,” TOI had reported.

That obscurity, as stated in the TOI report, has remained till date. The mutiny was quelled by the British by February 22 with Franco-Russo-Japanese help. After that, it was the time for conspiracy theories. Though there was little evidence on ground, the mutiny was linked to the Ghadar Conspiracy—efforts by the Ghadar Party to foment rebellion among Indian troops stationed abroad. The Ghadarites themselves took credit for it, though they got news of the mutiny only on March 2—the same day TOI carried the report—after the mutiny was suppressed. And they thought until April that Singapore was under rebel control.

Then there was the German conspiracy theory. At least one German prisoner took credit for inciting the Indian soldiers to mutiny. Plus the sepoys are believed to have received letters from their comrades fighting in Europe that the German king had converted to Islam and that it was not right to fight the forces of a Muslim king.

Then there was the more convincing theory of the sepoys rebelling due to their unwillingness to fight the forces of the Ottoman Sultan, the caliph of Islam.

But the real factor may have been a combination of terrible lapse in communication and leadership on the part of the British (the CO of the regiment was particularly unpopular among the troops and officers, both Indian and British. After the mutiny, he was dismissed from his post and retired from the Army) and a greater desire among the Indian troops to escape the horrors of European war—the latter observation also made by Japanese historian Sho Kuwajima.

On July 5, 1915, TOI carried the government’s explanation: “In view of the misrepresentations that have been made regarding the mutiny, we are authorized by the governor to state that no report whatever had reached His Excellency or the general officer commanding prior to the mutiny regarding any seditious tendencies in the 5th Native Light Infantry … No charge of disloyalty had ever been made to the government against the 5th Light Infantry … on the other hand, Government had received most positive assurances as to the loyalty of the regiment.”

Yet the sepoys were only loyal to one another in their regiments, battalions and companies as in the case of the Singapore mutineers. They gave no call for freedom or anything of that nature.

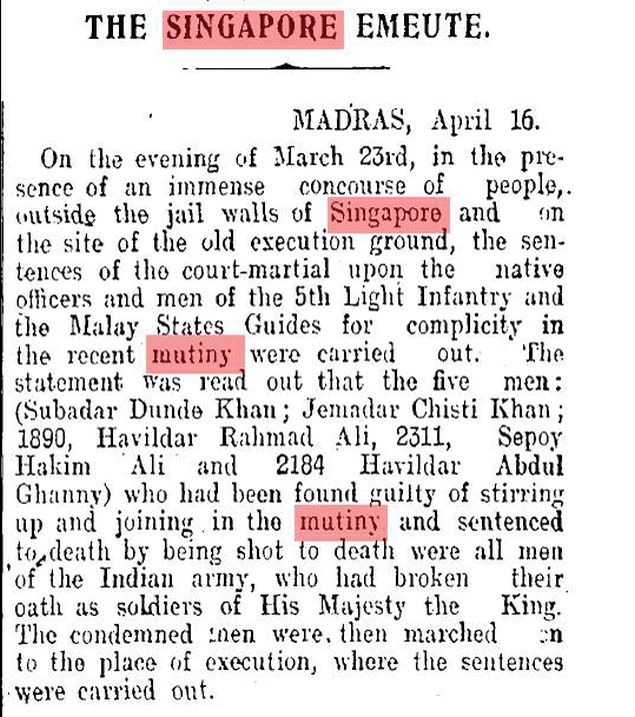

Snapshot of a TOI article from 1915 on the Singapore Mutiny

Nevertheless, in the immediate aftermath, there was disturbing talk about the loyalty of Indian troops, and the wisdom of trusting the security of big colonial possessions like Singapore to Indians was questioned too. But in a strange coincidence, exactly 27 years after the Singapore Mutiny, on February 15, 1942, 80,000 British-led Allied troops surrendered at Singapore to the Japanese of whom 40,000 were men of the Indian Army. Nearly 30,000 of them would eventually join (either voluntarily or under duress) the Indian National Army.

Buried in history

· 47 sepoys, NCOs and VCOs were executed after a general court martial

· The ringleaders were identified as Subedar Dunde Khan, Jemadar Chisti Khan, Havildar Rahmat Ali, Sepoy Hakim Ali and Havildar Abdul Ghani; Dunde Khan and Chisti Khan were shot first on February 21

· 64 others were sentenced to transportation for life or ‘sazaa-e-kalapani’

· No memorial or plaque whatsoever to the mutineers exist anywhere

· Mutineers till today are unfairly vilified in Western accounts

· Since most sepoys on trial and during court of inquiry clammed up, the full truth about the causes of the mutiny are not known till today

(Write to the author at manimugdha.sharma@timesgroup.com)

source: http://www.timesofindia.inditimes.com / The Times of India / News Home> India / by Manimugdha S. Sharma / TNN / August 03rd, 2014