INDIA:

Pratinav Anil argues that policies of the Congress and the Muslim elite ended up hurting Indian Muslims the most.

Unobjective commentators have, in the last decade, perfected the art of highlighting the tribulations of being a Muslim in “Hindu India” without contrasting them with the difficulties the same Muslim faced in “secular India” that supposedly existed before 2014.

Pratinav Anil is perhaps the only modern historian who has gone against this trend to put right the wilful muting of Indian Muslim history. His new book Another India: The Making of the World’s Largest Muslim Minority, 1947–77 is an in-depth analysis of anti-Muslim violence since Independence that exposes the Islamophobic facet of the country the Congress established in August 1947.

In simple terms, the question that Another India seeks to answer is: Was the Congress’s idea of India genuinely secular and based on communal equality? From the facts it lines up, the answer is ‘no’.

Riots and taunts

Not many know that the “most violent Hindu-Muslim conflagration of postcolonial India” was unleashed in 1964 in which a staggering 800,000 Muslims from Bengal were pushed into East Pakistan.

Indeed, it was under the Congress that the derisive “go to Pakistan” taunt was actualised when nearly 2% of the Indian Muslims were sent to Pakistan after being branded infiltrators who had sneaked in to convert Hindus to Islam. Before being expelled, they were dumped in makeshift camps on the border “like herds of cattle”, and forced to “sign papers declaring falsely that they were Pakistanis” when many of them were genuine Indians.

A large number of those who couldn’t be “sent to Pakistan” became the victims of the “riots galore” that dotted Nehru’s rule. The “institutionalised riot system” was so one-sided that Muslims made up 82% of the fatalities and 59% of the injured.

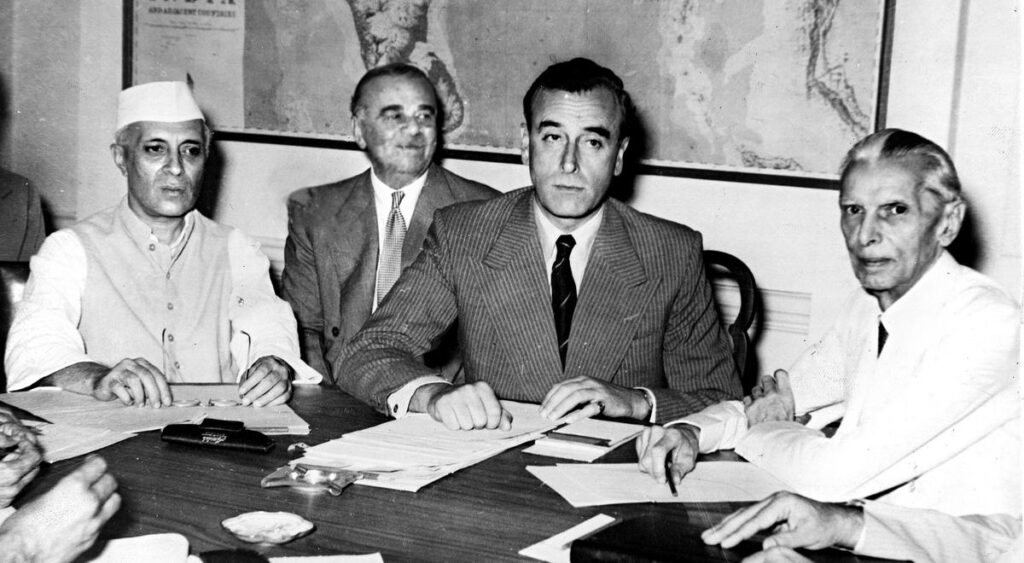

Prepossessed hostility towards Muslims was also the cause of the 1948 police action in Hyderabad which, for Anil, was “a mass pogrom” because it had resulted in the massacre of 40,000 Muslims, the rape of women, loot, arson, desecration of mosques, forcible conversions, and seizure of houses and lands. Nehru hastily suppressed the Sunderlal Report that brought out these facts.

Anil concludes that Nehruvian India was often “an Islamophobic agency” that wore secularism as “a fig leaf” to hide its pro-Hindu bias.

The Ashraf betrayal

But how did the Congress get away with its brazen marginalisation of Muslims? With the help of “nationalist Muslims” and “notables”, says Anil.

The former were mostly Muslim Congressmen who harmed their community by conflating India’s progress with that of the Congress; shielding Congress from criticism by blaming Muslim communalists for Partition, and placing the constitutional protection of the shariah above the community’s political rights.

The “notables” comprised upper-class Muslims (the ashraf) such as mutawallis (custodians of waqf properties), waseeqadars (princely pensioners) and waaqifs (dedicators of properties for waqf) all of whom used their aristocratic agency to feather their nests in the guise of working for the community’s economic development.

A major preoccupation of these patricians was “the preservation of distinctive elements of Muslim culture in a non-Muslim environment.” Backing them to the hilt were the ulama, especially those belonging to the Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind which Anil calls a branch of the Congress in all but name.

The “ashrafised” Islam that the ashraf-clergy nexus promoted secured the class interests of the ashrafs and almost totally ignored the plight of common Muslims.

In a scathing attack on the Muslim elite’s obsession with the shariah-based Personal Law, Anil says that it furnished the patriarchs with “a private fiefdom to do as they pleased” without mitigating the community’s “despondent public existence in an Islamophobic society.”

No space for scrutiny

As a consequence, Muslim politics had no room for “trade unions, mass protests, anti-discrimination legislation, and subaltern solidarity” while it had plenty for “high cultural totemic symbols such as the AMU, auqaf, Urdu, and the sharia.” This suited the ruling “Hindu Congress” because a politically empowered non-Hindu group was not in its interest.

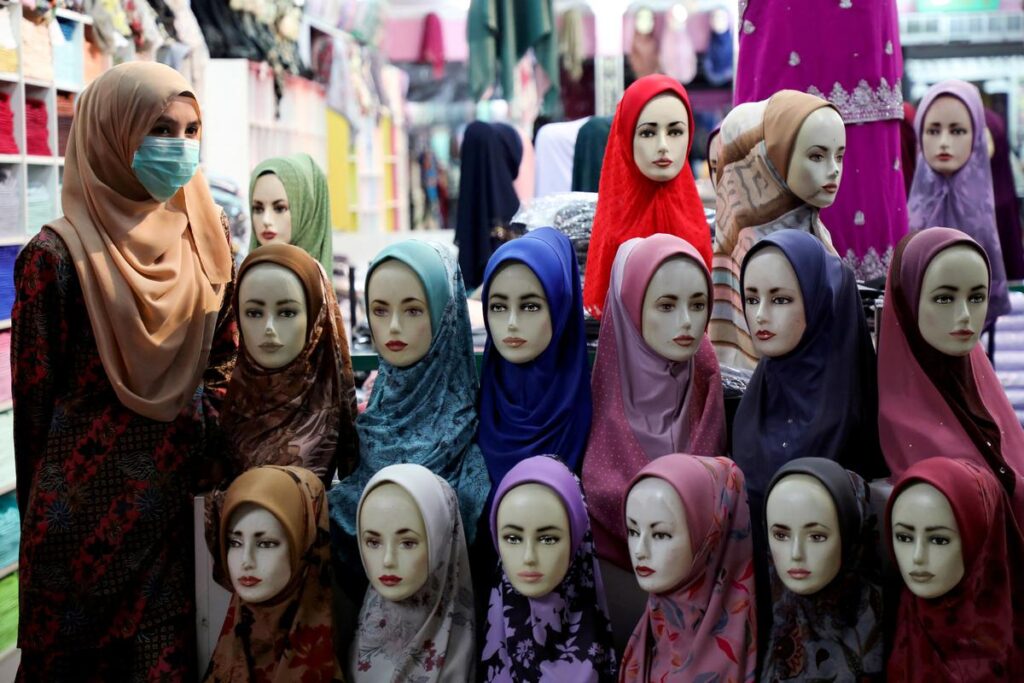

Even today the ashraf-clergy alliance prioritises religion and religious symbolism over social cohesion and political participation. If, for instance, ashraf-backed madrasas are fixated on anachronistic medievalism, many clergy-endorsed secular English medium schools controlled by wealthy Muslims promote religious identitarianism by making the skull cap (for boys) and the hijab (for girls) a mandatory part of the uniform.

This self-ghettoisation, which is nothing short of an attempt to discourage the enrolment of non-Muslims in Muslim schools, sustains itself on the fear of the other and has the potential to render Muslim students incapable of living in multi-religious and multi-cultural societies after graduation.

Given this sad state of affairs, Another India couldn’t have come at a better time. Its neoteric narrative is not just a searing exposé of Congress’ betrayal of trustful Muslims who stayed back in India after rejecting Pakistan; it is also an invitation to Indian Muslims to acquire a sense of critical thinking and break free from the serpentine stranglehold of the ashraf-clergy alliance that is hell-bent on denying them the heaven-ordained right to intellectual liberation.

Another India: The Making of the World’s Largest Muslim Minority, 1947-77; Pratinav Anil, Penguin/ Viking, ₹999.

The reviewer is Secretary-General of the Islamic Forum for the Promotion of Moderate Thought.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by A Faizur Rahman / February 04th, 2024