NEW DELHI :

For an ephemeral form such as live theatre, where the works of most masters, especially theatre directors, disappear in the mist with their passing, it’s heartening that Ebrahim Alkazi’s legacy has been preserved for a posterity he had emphatically staked a claim to more than a half-century ago.

The grand old man of Indian theatre has passed into eternal incandescence, joining the extended roster of eminent luminaries who have left us this year. The extraordinary Ebrahim Alkazi wore many hats – unparalleled theatre doyen, a driven connoisseur of the arts, cultural ambassador – and leaves behind a staggering legacy as one of the most distinctive architects of 20th-century Indian theatre. He was 94, and the high point of his career in the performing arts was arguably his 15-year tenure as the director of the National School of Drama (NSD), from 1962 to 1977. Such was his trailblazing contribution to theatre and its practice, that the Sangeet Natak Akademi accorded him their highest honour, the Akademi Ratna, for lifetime achievement in 1967. No person below the age of 50 is ordinarily considered for this: Alkazi was just 42 when he received it, and remains one of its youngest recipients.

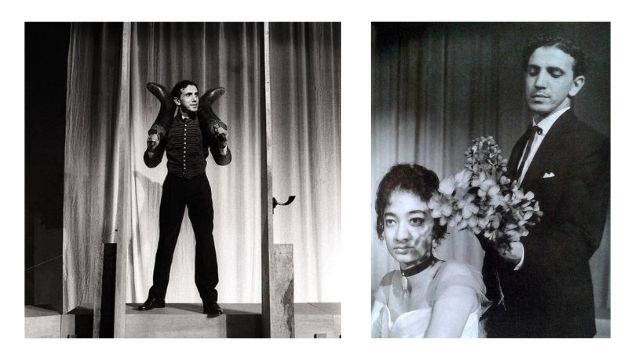

Alkazi grew up in a household of nine children. His family migrated from sun-kissed Unaizah in Saudi Arabia to salubrious Pune, where he was born in 1925, coming of age during World War II. He juggled Arabic tutelage and lessons on the Quran at home with convent education in English and French at the historically significant St Vincent’s High School. “That [blend] had its limitations but it opened up a whole world for me, almost half of mankind,” he told television anchor Syed Mohd Irfan. It was a charmed childhood in which books were never out of reach. From staging one-act plays at school, Alkazi moved to mature productions like Salomé and Othello at St Xavier’s College, with the charismatic Oxford-returned Sultan ‘Bobby’ Padamsee’s Theatre Group. The latter’s untimely demise in 1946 saw Alkazi take over the reins of the group; he later married Padamsee’s sister, Roshen.

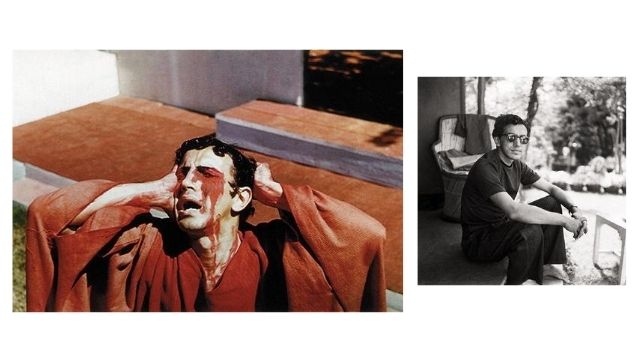

In the 1950s, after a somewhat unsatisfactory stint as an acting student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, he returned to an India on the cusp of a first-wave cultural renaissance. “[RADA was] a rather closed institution, one which had not opened itself out to living theatre movements in other parts of the world,” he said in The Journal of South Asian Literature. That said, his own output as director with Theatre Group, and later Theatre Unit, was primarily productions of European and American plays in English. Working out of a bustling Mumbai terrace, his erstwhile collaborators included Gerson da Cunha, Satyadev Dubey, Usha Amin and Alaknanda Samarth.

One show particularly memorable was Alkazi’s 1959 production of August Strindberg’s Miss Julie, based on a blue-blooded woman’s tryst with her intensely impassive valet, in which he starred opposite Samarth. In Shanta Gokhale’s The Scenes We Made, Samarth remembers the play as a series of heightened, distanced, restrained images: “the final exit, an excruciatingly slow, steady walk on high heels through a guillotine-like door on to a ramp horizontal to the lit cyclorama.” Alkazi’s signature tools and approaches were crystallised during this phase. “I acquired administrative skills, learnt to employ ancient Indian arts like Iyengar Yoga and Kathakali in the practice of theatre, communicated a sense of social responsibility to my troupers who learnt to value their group activity as professional, meaningful, relevant, transformative,” he told journalist Sunil Mehra, of this decade-long inning of innovation and consolidation.

Alkazi was hand-picked by the government to lead the Akademi’s newly formed drama school in Delhi, but after declining several times, he finally took over as NSD’s director in 1962, succeeding Satu Sen, the pioneering lights technician from Bengal. “They gave me a carte blanche to take charge, laying out the red carpet,” he remembered. Under Alkazi, the foundation for the NSD’s multi-pronged pedagogical programme was set in stone. It presented a coalescing of a Western approach to drama with India’s ‘theatre of roots’. And, as a director with a constant supply of dedicated actors, students and alumni (some of whom joined the school’s professional repertory company) alike, he was able to add substantially to his own distinguished oeuvre.

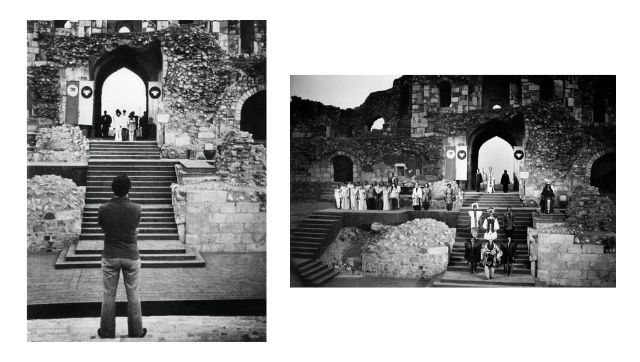

Some of his best-known works were staged in historical monuments and attracted audiences from a wide cross-section of society, from ticket-paying middle-class audiences to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was astounded by this rooted-yet-global brand of Indian theatre. His prized troika of productions include Mohan Rakesh’s Ashadh Ka Ek Din, Girish Karnad’s Tughlaq and Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug, one of his earliest NSD stagings in which he commandeered what was essentially a radio play to create a spectacle in the mould of classical Greek theatre, with the bolstered ruins of Feroze Shah Kotla providing a staging of multiple levels, and unmistakable political echoes. The play placed Alkazi firmly on the national stage, even if the plays didn’t really cross over. When asked by Irfan about why the works did not ‘reach the people’ they were ostensibly intended for, he replied dismissively: “That’s their fault. We toured a lot with it.” Even in its large open-air spaces, the notion of the NSD as an insulated echo chamber set root in the Alkazi era.

Among the many illustrious graduates of the NSD who benefited directly from his tutelage, were actors like Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Pankaj Kapur, Rohini Hattangadi and Surekha Sikri; and directors like Sai Paranjpe, Prasanna, Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry and Om Shivpuri — all stalwarts of the theatre business spanning generations and sensibilities. In his memoir, And Then One Day, Shah writes, “In Alkazi I had at last found an inspiring teacher, one who liked and appreciated me and didn’t make me feel like a fool, one who was interested in helping me improve my mind, and pushed hard to make me realise the potential he perceived in me.”

In the initial years, Alkazi had his students dig up the backyard of the rented house in New Delhi’s Kailash Colony, that the school operated from, to create a performing stage. Later, he designed two new theatres at the NSD’s present location at the Bahawalpur House, the former residence of the Nawab of Bahawalpur in Delhi. A 200-seater studio theatre, and the open-air Meghdoot Theatre, under a banyan tree, both of which are now housed in a complex christened the E Alkazi Rangpeeth in 2017, to mark 50 years of their inception.

In 1977, Alkazi resigned from the directorship of the school that had become synonymous with his identity. In Anil Dharker’s Icons, da Cunha describes the ‘abdication’ as “a casualty of the bureaucracy and the lobbies he had successfully skirted for many years [also known as] the notorious Delhi Syndrome.” There was an emergent tribe of detractors who enumerated the chinks in his armour, from an unmistakable hubris to an autocratic administrative flair to the creative belligerence and brute stamina that he brought to the rehearsal room, albeit in the kind of controlled environment that his protégés and imitators were loathed to replicate. Shah places his mentor’s processes in the context in an interview, “Any theatre activity is not a democratic process. There has to be a leader, so the charge that Alkazi was autocratic is baseless. Rather than his so-called elitism and arrogance, his students have inherited his discipline, dedication and ability to work himself to the bone. NSD has never quite been the same, his successors unable to shrug off the ghost of Alkazi that hovers around all the time.”

In Mehra’s 1996 article, director Anuradha Kapur says, “Undeniably, he professionalised theatre. One’s differences may be ideological vis-a-vis his characters’ sexual politics, motivations. But then he was a creature of his time.” On his perceived non-combativeness during the Emergency, Alkazi said, “Cheap sloganeering is not the work of academic institutions,” calling attention instead to the political subtext of the plays he staged around then. In 1975, he had said, “I think there is a very close connection between politics and theatre, between social conditions and theatre. I think theatre needs to play an even more active part in shaping the way people live, in creating a progressive form of government which is meaningful to large numbers of people.”

Of course, the closing of a chapter marked the beginning of another innings that took up much of the maestro’s later decades. With Roshen, he founded the Art Heritage Gallery in Delhi the same year he bid adieu to theatre (although there would be an ill-fated comeback). The full extent of his journey was the subject of a travelling exhibition and book, The Theatre of E. Alkazi – A Modernist Approach To Indian Theatre, put together by his daughter, theatre director Amal Allana, and her husband, the stage designer Nissar Allana. As this writer had written about the showcase, “Panels emblazoned The Alkazi Times present the signposts of Alkazi’s life as news clippings, interspersed with actual microfiche footage — ascensions of kings and prime ministers, declarations of war and independence, and even snapshots from theatre history. It is certainly monumental in scale, full of information about Alkazi’s genealogy, childhood, education and illustrious career. While there is the slightest whiff of propaganda, it is whittled down by Allana’s skills as a self-effacing raconteur during the talks. Her accounts are peppered with heart-warming personal anecdotes that give us a measure of the real person behind the bronzed persona.”

For such an ephemeral form as live theatre, the works of most masters, especially theatre directors, disappear in the mist with their passing. It’s heartening that Alkazi’s legacy has been preserved for a posterity he had emphatically staked a claim to more than a half-century ago.

— All images via Facebook

source: http//www.firstpost.com / Firstpost / Home> Art & Culture> News / by Vikram Phukan / August 05th, 2020