NEW DELHI:

By equating Akbar and Aurangzeb, proponents of Hindutva show they prefer to settle present-day disputes with the weapon of history, real or imagined.

Those who believe in the Hindutva agenda cannot find a distinction between the diverse Muslim Indian leaders of the past. It is in this light that persuasive attempts have been made to link Akbar and Aurangzeb, the two Mughal emperors who should be seen at the opposite ends of the spectrum of religiosity and pluralism. An excerpt from the forthcoming book, Being Muslim in Hindu India.

For the votaries of Hindutva, all Muslim Indian rulers of medieval India are the same. Be it the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, the Deccani sultans or the Mughals, their names are incidental, even superfluous. They were all Muslim kings! It does not matter that no Muslim king governed by the principles of Islam and most of their decisions were taken based on political needs. Their alliances and conflicts were all entered for personal aggrandizement. No king waged a jihad, a crusade. The fight was not to uphold the supremacy of any faith, but to expand fiefdom, kingdom or empire. To the rabble-rousing Hindutva brigade, it matters not that there were Muslim commanders of Hindu armies, and Hindu governors in charge of the so-called Muslim armies.

For instance, Raja Jai Singh led Aurangzeb’s armies against Shivaji, just as Raja Man Singh had led the Mughal forces against Rana Pratap in the time of Akbar. At the same time, Hakim Khan Sur led Rana Pratap’s forces against the Mughals! Violence was a regular feature of premodern Indian kingship, and there were no religious divisions when it came to violence. All kings, all dynasties, were violent — right from the Nandas and Mauryas to the Sultanate and Mughals, everyone. From Kalinga to Panipat, the story was the same.

However, these facts are for the discerning. For the Hindutva proponent with a clear agenda of ‘we’ and ‘they’, the important basis for distinction is the name of a Muslim king. It is under this light that persuasive attempts have been made to link up Aurangzeb and Akbar, the two Mughal emperors hitherto seen at opposite ends of the spectrum of religiosity and pluralism.

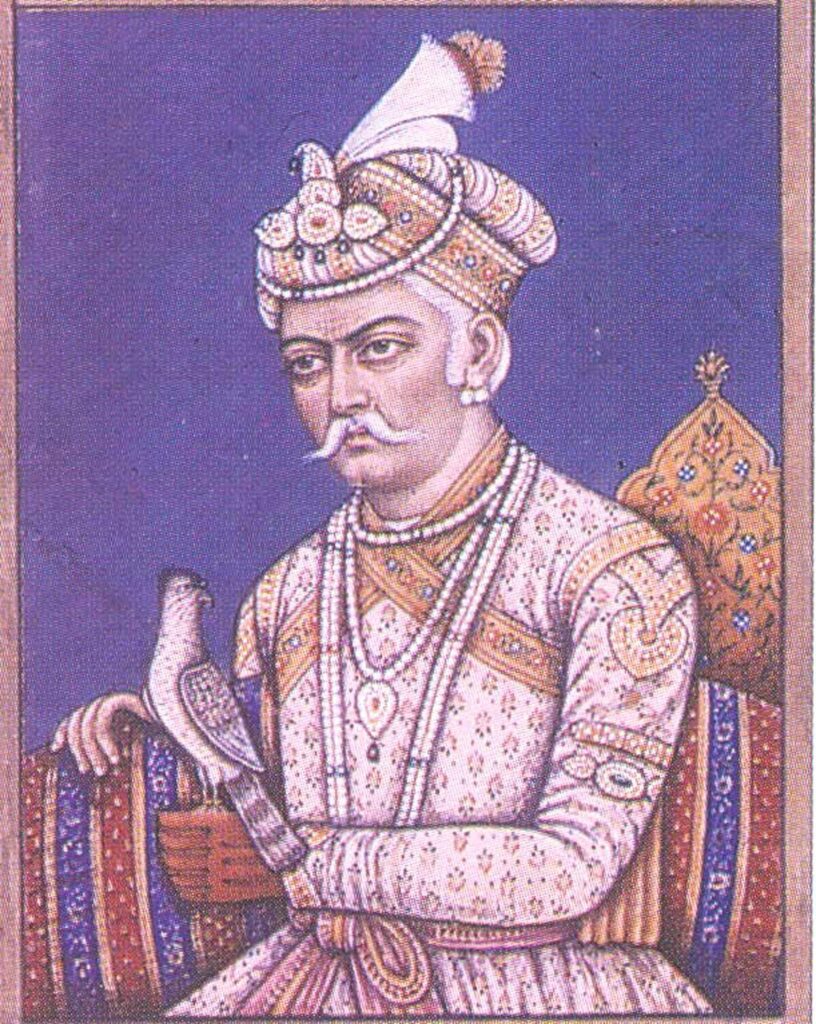

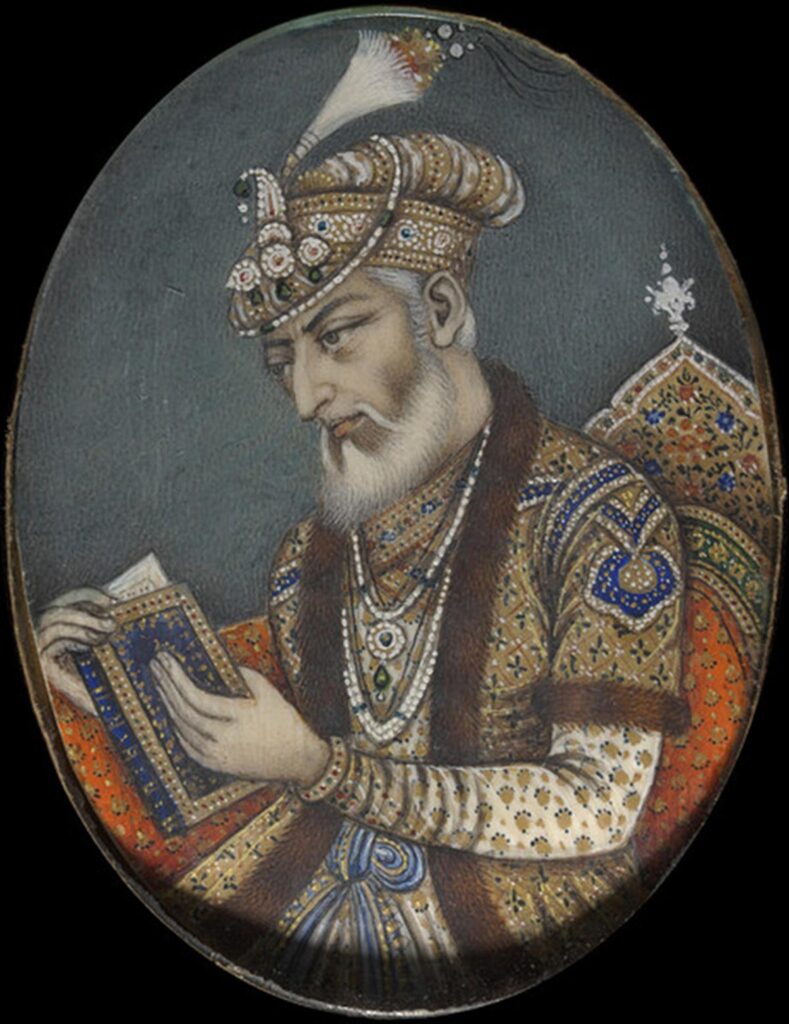

The former has historically been projected as a bigot, the man who charged jizya, demolished temples and withheld state patronage to arts and culture. The latter has been hailed for the breadth of his vision, his ability to forge matrimonial alliances with the Rajputs — taking their princesses in marriage while they remained practising Hindus — initiating a dialogue with priests and practitioners of all faiths, even collecting the best principles of various religious denominations to come up with Deen-e-ilahi, a new faith that sought to appeal to the broader instincts of the educated.

The faith died with Akbar, but the fact remains that Deen-e-ilahi and the underlying principle of Sulh-i-Kul were probably among the earliest attempts at finding a solution to inter-faith differences. ‘Akbar supervised translations of Singhasan Battisi, Atharva Veda, Mahabharata, Harivamsa and other scriptures into Persian,’ says historian Shireen Moosvi, professor at Aligarh Muslim University, adding that Sulh-i-Kul was the result of genuine considerations to suit the needs of a multi-religious country like India. Much before the Indian Constitution made secularism the touchstone of democracy, Akbar had practised it.

Now, the difference between Aurangzeb and Akbar, clear as night from day, is being gradually blurred. No, despite serious attempts by historians, the polity is not looking at Aurangzeb afresh; in the mind of the common man, he continues to be a destroyer of temples, one guilty of regicide, patricide, fratricide and what have you. In February 2023, the name of Aurangabad, the city where he is buried in a simple tomb, was changed to Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar, after Chhatrapati Shivaji’s son, who was executed by Aurangzeb in 1689.

Repeated attempts are being made to nibble at Akbar’s greatness, letting us know through an incident here, a rechristening attempt there, that Akbar was not so great after all. That the Rajputs were better, that Akbar was a Mughal and hence incapable of being our hero. The attempt is not only to rewrite history, but also to deprive contemporary Muslims of their heroes, in whose actions they could take pride, and icons they could quote in conversations as their contribution to the nation. The stray barbs about the Taj Mahal or the Ajmer Fort are actually not isolated or spontaneous utterings of a loose cannon, but a deliberate ploy to take the sheen off the accomplishments of the Mughals — and by extension, modern-day Muslims—who are now held accountable for all the battles and bloodshed of the past.

In the grammar of Hindutva votaries, you see, every Muslim king was a Mughal, and every Indian Muslim of modern India is responsible for the failures and sins of the Mughals…. The derogatory ‘Babur ki Aulad’, a term often heard since the Babri Masjid–Ramjanmabhoomi dispute, stemmed not just from a political mindset, but a much deeper and divisive ideology. It is this ideology that refuses to take a dispassionate look at our past. It prefers rather to settle present-day disputes with the weapon of history, real or imagined…. In their world of binaries, you are either with them or against them. The recycling of Hindutva mythologies is merely an attempt to fuel modern-day bigotry. Nuanced study, not sweeping generalisations, is the need of the hour.

Being Muslim in Hindu India; Ziya Us Salam, HarperCollins, ₹599.

Excerpted with permission from HarperCollins.

ziya.salam@thehindu.co.in

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books>Review / by Ziya Us Salam / November 17th, 2023