NEW DELHI :

“Karkhandari” as per Professor Gopi Chand Narang (1931-2022), a noted Urdu scholar, literary theorist, and linguist, “is a social dialect spoken mainly by the artisans, traders, craftsmen and labourers of old Delhi.”

Representational image of a book. Photo: Pavan Trikutam/Unsplash

Dehli, not Delhi. Yes, you read that right. For this is how it is spelt in Urdu, the language whose birth and development is often attributed to purani Dehli or Shahjahanabad. But, it is not the only language to be spoken in the walled city. In fact, people from old Delhi can often be found to be speaking in a language which is closer to the Karkhandari dialect. It is not very uncommon to hear sentences like vai, itte din ka the? instead of “bhai, itne dinon tak kahan the?” (Bro, where were you for so long?), while passing through the kuchas (lanes/small streets) of the walled city.

“Karkhandari” as per Professor Gopi Chand Narang (1931-2022), a noted Urdu scholar, literary theorist, and linguist, “is a social dialect spoken mainly by the artisans, traders, craftsmen and labourers of old Delhi.” In his monograph (1961) titled “Karkhandari Dialect of Delhi Urdu,” he lists out the names of the locales of old Delhi where the dialect is spoken. “The Karkhandari areas outside the walls of the old city,” adds Narang, “include Mohalla Kishan Ganj, Shish Mahal, Qasṣāb Pura, Beri Wälä Bagh and a few lanes in Bära Hindu Rao.”

Abu Sufiyan, a resident of old Delhi and founder of Purani Dilli Walo Ki Baatein, says that it is not a dialect of the yesteryear. “Karkhandari is still spoken by the working class of the old city and their family members,” adds Sufiyan. Earlier this year, a book titled Nirali Urdu by M.A. Mughni Dehlavi was republished in India, nearly after a century of its publication, and it is believed to be the first and the only book in the Karkhandari dialect of Delhi Urdu.

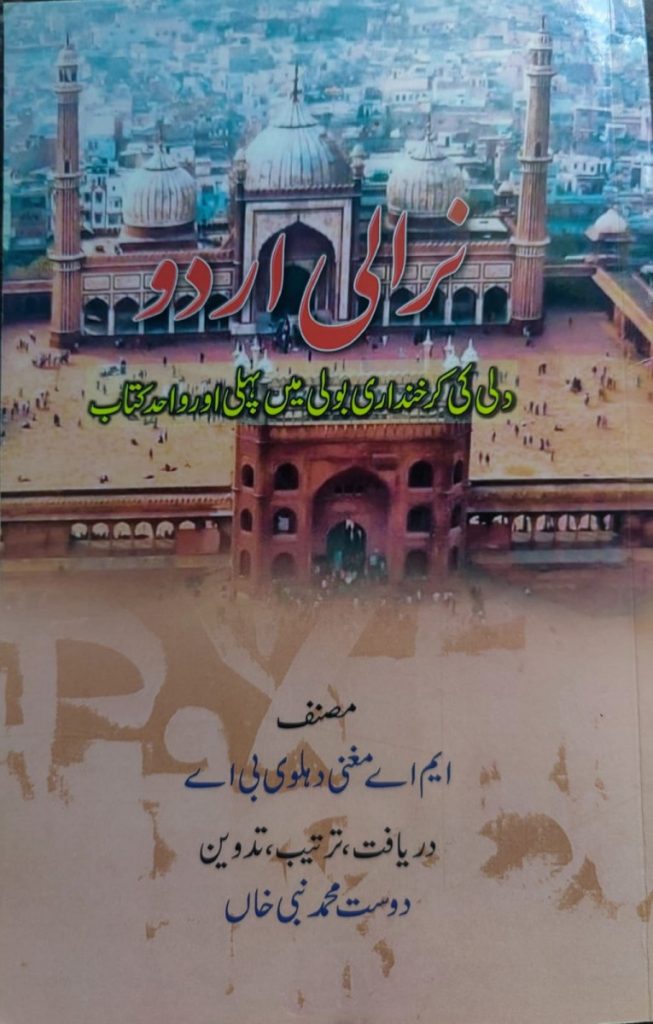

New book cover of Nirali Urdu. Photo: Arranged by the author

In fact, there is a difference of opinion on the year of publication of Nirali Urdu. According to Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee (1917-2005), a researcher, linguist and lexicographer, the book was first published in 1927, while Dost Mohammad Nabi Khan, a compiler and editor of the latest version of the book, on the other hand, argues that it was first published in 1932.

To substantiate his claim, Khan notes that in one of the stories in the book, the narrator talks about watching the second talkie film of India, ‘Shirin Farhad,’ which was only released in May 1931. He also notes that as per Google Books as well, it was published in 1932 by Daftar Nirali Urdu. Notably, the copy of the book available on the Rekhta website does mention Daftar Nirali Urdu as its publisher, but the year of publication is missing. However, where both Haqqee and Khan seem to agree is that after its initial publication, it became nayaab (rare/scarce) and was hardly available in the market.

Khan, who was born and brought up in Dehli and who loves collecting books on the city, narrates an engrossing story about his ‘discovery’ of Nirali Urdu in its muqaddama (introduction) to the book. Khan came to know about this book when, several years ago, he was surfing through the booklists of various Pakistani publications online.

“Both Nirali Urdu and its author M.A. Mughni were new and unfamiliar to me. Topics included in the book and its writing style were literally Nirale (unique) and offbeat. It was nothing short of a discovery for me,” he writes. With the help of a friend in Lahore, he procured the book and occasionally started posting excerpts from it on Facebook. The book was eventually re-published in January 2024. However, it is not just a re-publication of what was originally published in 1932 and reprinted in 2017 (in Pakistan), for there are useful additions to the current version. Khan has added a short Glossary (Farhang), a few explanatory notes (Wazahati Note) and some proverbs and idioms of Kharkhandari to it.

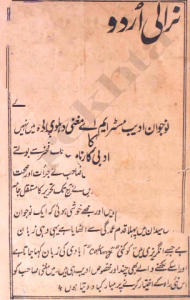

Old book cover of Nirali Urdu. Photo: Arranged by the author

Apparently, unlike most of the books around Delhi, the book does not contain stories about monuments or history. Rather they are about the people, society and scenes of everyday life of ordinary people of Delhi in the 1920s. In other words, in Nirali Urdu, the people of Delhi don’t go for Lal Qile Ki Sair or Qutub Minar Ki Sair, they go for Baiskop Kee Sail (Biscope Ki Sair/ outing to a bioscope show) and Jaloos Kee Sail (Juloos Ki Sair/excursion to a procession). However, in some stories, there are references of excursions to monuments as well. For example, sample this excerpt :

“Aaj subo mein zari aawere utha tha. is liye apne aap kuchh aisi khud bar khud ghabri hui ki mein hadbada ke bistare pe se khada hoke baith gaya aur is fikhar mein pad gaya ki kain sail ko chalna chaieeye. Magar akele jana to theek nai tha. Isliye apni jigri yaar ke makkaan pe ponch kar vise aawaz di. “Abey muntiyaaz, o muntiyaaz”. muntiyaaz wabsurrti shakl bana kar bahar aakar kaine laga, abey kyun cheekhe peete ja riya hai. Meine kaha pyaare khafa kyun hota hai ya shikal hi aisi hai. Dekhta nai kis zor se ghata chha rahi hai. chal mandarsa (Safdar Jang) todi chalein. Bada lufat aa riya hoga…”

The above text can be translated as :

This morning, I woke up a little early. That’s why I woke up with a start and started thinking about going for an excursion somewhere. But it didn’t feel okay to go alone. So I landed at my best friend’s place and called out to him. “Aye Muntiyaz, O Muntiyaz.” Muntiyaz appeared with an agitated face and said, “Oye, why are you shouting?”

“Why are you getting angry dear, or is your face like this only?, I replied, adding Don’t you see how lovely the weather is? Let’s go to Safdar Jang’s tomb. It must be a great fun there…”

While the text does not read totally distinct from standard Urdu, but certain words are spelled and pronounced differently. For example, in Karkhandari dialect, Subah is Subo, Sawere is Aawere, Makaan is Makkaan, Fikr is Fikhar, Shakal is Shikal, Madarsa is Mandarsa and Lutf is Lufat.

There are a total of 31 short stories in the book. It also has stories titled Dilli Ke Panjabi Musalman (Delhi’s Punjabi Muslim), Eeed Ka Pologram (Eid Ka Program/the program for Eid), Kishmishi Din Kee Sail (Krismas Din Ki Sair/outing on Christmas day) and Mushahare Kee Sail (Mushaire Ki Sair/ outing for a mushaira).

In short, Nirali Urdu is full of unique and offbeat stories from Delhi. If you can read Urdu script and are interested in Delhi, it becomes an essential read.

~~~~

Although there is no shayari in the book, even in the story about a Mushaira, one finds the same in the Balraj Sahni and Farooq Sheikh starrer Garm Hava that was released after four decades in 1974. The tongawala who drives Salim Mirza (the protagonist of the film played by Sahni) to his Karkhana (factory) can be seen reciting a couplet in Karkhandari Urdu. While commenting on the tragedy of partition and its impact on Indian Muslims, the tongawala, in the opening sequence of the film, recites the following verses:

Wafaon ke badle jafa kar riyae

Mein kya kar riyaun tu kya kar riyae

This is a couplet from a Ghazal in Karkhandari Urdu written by Majeed Lahori (1913-1957), a noted poet-satirist, humorist and journalist. The full ghazal reads as follows :

Wafaon ke badle jafa kar riyae

Mein kya kar riyaun tu kya kar riyae

Mein jo kar riyaun bhala kar riyaun

Tu jo kar riyae bura kar riyae

Abey todta kyun hai tun vis ke dil ko

Jo dil apna tujh par fida kar riyae

Sanbhal kar qadam vis ke kooche mein rakhiyo

Suna hai wo fitne bapa kar riyae

Udu se bhi waade mujhe bhi dilase

Mein hiryaan hoon tun ye kya kar riyae

Kiya hai ata darde dil jis ne mujhko

Wahi darde dil ki dawa kar riyae

Majeed aaj bhi shaad wa aabad hoon mein

Karam mujh pe mera khuda kar riyae

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Books / by Mahtab Alam / July 29th, 2024