NEW DELHI:

Oral historian Sohail Hashmi into a new wave of dissent in Urdu poetry at a Delhi workshop earlier this month. ‘It’s asking important questions, raising serious issues.’

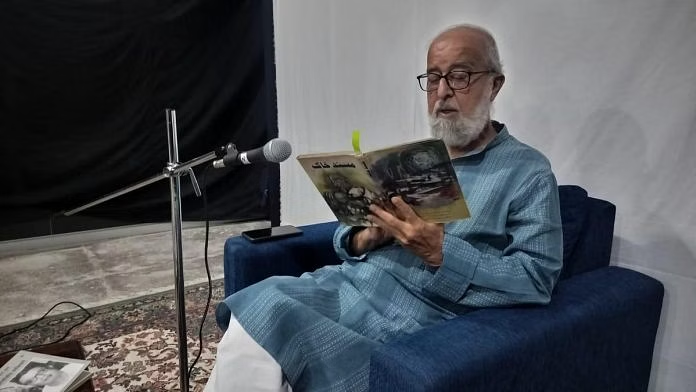

Heritage conservationist Sohail Hashmi reading out poems by contemporary Muslim writers at his Urdu poetry workshop earlier this month | Photo: Heena Fatima | ThePrint

New Delhi:

In a quiet corner of Delhi’s Neb Sarai, a small band of Urdu poetry lovers gathered for an evening of verse. But this time, it wasn’t love or heartbreak in the air—it was words of protest, identity, and defiance.

At his Urdu poetry workshop at the NIV Art Centre on a September Sunday, oral historian and heritage conservationist Sohail Hashmi skipped nostalgic classics by the likes of Rahat Indori, Parveen Shakir, and Munawwar Rana. Instead, he chose hard-hitting political poems by contemporary Muslim poets to demonstrate how modern Urdu poetry is changing.

“After the 1992 Babri Masjid incident, there was a major shift in Urdu poems. Urdu poets are now questioning the dominant narrative constructed in the society about minority communities,” Hashmi told ThePrint.

Seated on a plush blue chair placed on a Persian rug, Hashmi explained to the audience that Urdu nazms (poems) have become a space for protest. He said there are two broad streams of Urdu poetry.

The first category includes poetry with beautiful rhymes and words, making it easy for readers to remember. Its main themes revolve around love and the pain of separation.

The second category, which he called “poetry of thought”, tackles deeper, more serious issues.

“This poetry is asking important questions, raising serious issues,” Hashmi said. “And it’s the kind of poetry that the mainstream does not acknowledge.”

Throughout the workshop, Hashmi let the poetry speak for itself by reciting works from several contemporary poets, including Ibn-e-Insha, Gauhar Raza, Nomaan Shauque, and Ikram Khawar.

‘Blunt and merciless’

New Urdu poetry is more about thought than pure emotion. This poetry, said Hashmi, is both a political commentary and a snapshot of “new India” through Muslim eyes. And many poems address the “Muslim identity crisis”.

One such poem, by Ikram Khawar, is titled Haan Main Musalmaan Hoon (Yes, I am a Muslim). Hashmi picked up a volume from the table and read aloud:

Haan main musalmaan hoon

Nahi kahoonga main, jaise tum insaan ho

Bagair kisi sharm ya duhai ke,

Bagair kisi safai ke

Main khud ko dekhne se inkaar karta hoon, tumhari aankh se

(Yes, I am a Muslim

I won’t say, like you, that I am human

Without shame or plea,

Without any justification,

I refuse to see myself through your eyes).

After finishing the poem, Hashmi explained that it rejects the imposed, stereotypical image of Muslims and challenges the dominant narrative. The refusal to see oneself through the lens of others, he said, is an act of defiance.

One woman in the audience expressed concern: “That’s the protest in the poem, but this kind of poetry is being pushed out of the mainstream.”

Hashmi, however, countered that while this poetry may not be amplified in popular culture, it has become the dominant voice in contemporary Urdu literature.

“Genuine poetry rarely reaches mainstream platforms—it doesn’t appear on news or TV channels. Instead, it finds its place in literary magazines and circles, and thrives in poet gatherings,” he said.

He added that much of what gets wider exposure is often confined to superficial themes, while deeper, uncomfortable subjects in Urdu and Hindi are pushed into niches where they are appreciated only by a few.

Hashmi then recited Nomaan Shauque’s Lakshman Rekha, a poem that asserts free will in a time when even personal choices—like diet—are policed. It strikes a rebellious note:

Nahi, aap nahi samjha sakte mujhe jeene ka maqsad

Nahi bata sakte, kitni door tehelna

Kitni der kasrat karna zaroori hai, tandrust rehne ke liye

Khane ke liye, gosht munasib hai,

Ya saag, sabziyan

Rone ke liye munasib jagah, daftar hai ya bathroom,

Mujhe samjhana mushkil hai

(No, you cannot explain the purpose of my life to me.

You cannot tell me how far to wander

Or how long to exercise to stay healthy.

Whether meat is suitable for eating,

Or if vegetables are better.

Where it’s appropriate to cry, whether an office or a bathroom.

It’s difficult to explain these things to me).

Hashmi pointed out that poems on victimhood and oppression are becoming less common in Urdu. While these performed a cathartic role for those feeling helpless due to the “government’s marginalisation of minorities”, there’s a new trend now.

“Urdu poetry is moving away from generality toward specificity,” he said. “These questions (in poems) are very direct, addressing the issue bluntly and absolutely mercilessly.”

Shrinking spaces, empty chairs

The COVID-19 lockdown, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), and the rise of religion-based politics have given poets new urgency. Across languages, from Urdu and Hindi to Oriya, poetry has become a space for asking hard questions, according to Hashmi.

Hashmi recited Darsgah (Academy), a poem by scientist Gauhar Raza, which addresses the 2020 attack on JNU students during the anti-CAA protests:

Darsgahon pe hamle naye to nahin

In kitabon pe hamle naye to nahin

In sawaalon pe hamle naye to nahin

In khayalon pe hamle naye to nahin

Gar, naya hai kahin kuch, to itna hi hai

tum mere des mein laut kar aaye ho

par hai surat wahi, aur seerat wahi

sari vehshat wahi, sari nafrat wahi

kis tarha chupaoge pehchan ko?

gerue rang mein chup nahi paoge

(Attacks on colleges are not new,

Attacks on books are not new,

Attacks on questions are not new,

Attacks on ideas are not new.

If something is new, it is only this:

You have returned to my country,

But the appearance and character remain the same,

The same savagery, the same hatred.

How will you hide your identity?

You cannot conceal it in the colour saffron).

Hashmi then criticised Hindi kavi sammelans (poetry conventions), for promoting misogyny. He said many of these events focus more on storytelling than actual poetry.

“They mock overweight, bald, and dark-skinned people. The audience claps along claps and enjoys it without questioning,” he said.

He also weighed in on the erosion of literary spaces— Hindi and Urdu poets are emerging and voicing dissent but they struggle to find a platform. Because many publishing houses are shutting down or playing it safe, and demand for books is low, many new writers have to pay to get their work published.

Ironically, Hashmi’s event had a low turnout, with only five attendees—something that surprised the organisers. Aruna Anand, co-founder of the NIV Art Centre, told ThePrint that their monthly art sessions are usually full, attributing the empty chairs to the wider crisis confronting the Urdu language.

But Hashmi was not overly perturbed. He argued that poetry that addresses deep social questions will ultimately prevail and even revive the language.

“The poetry of thought is the poetry that eventually survives,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

source: http://www.theprint.in / The Print / Home> Features> Around Town / by Heena Fatima / September 28th, 2024