East African Asian society was complex and contradictory as any truly multicultural society needs to be, and perhaps as only Indians can make it

Toronto, CANADA :

It is amusing to contemplate that if an Indian man, one afternoon in March 1498, had been able to swim, he would have escaped capture by Vasco da Gama off the Mozambique coast, and the world might have been different. The Indian, whose companions had managed to swim away, was called “Davane” by his captors; he was from the Gujarati city of Khambat (Cambay). Davane gave advice to da Gama on local matters and even assisted him in outwitting the local sultan, so that the Portuguese ships eventually anchored safely in Malindi, up north in present-day Kenya. Here he took a pilot, who was possibly a Gujarati, and reached the Malabar coast.

Portuguese sailors plying the Indian Ocean thereafter often wrote about the presence of Indians and Indian ships in Kilwa, Mombasa, and Malindi. Around 1500, Captain Duarte Barbosa observed, “These ships of Cambay are so many and so large, and with so much merchandise, that it is terrible to think of so great an expenditure of cotton stuffs as they bring.” The trading connection between India and East Africa is actually even older, as the carving of a giraffe on a wall of the Konark sun temple indicates.

It was in the nineteenth century, however, that Indians began arriving in numbers to trade and settle in Zanzibar, which was by then a major metropolis in the Indian Ocean with international connections, and home to the ruling Omani sultans. The more enterprising men ventured off to the small towns dotting the mainland coast. Most Indians arrived penniless from their drought-prone villages in Kathiawad and Kutch, and remained modest traders, but a few of them went on to become veritable merchant princes with spectacular wealth. Among them were Jairam Sewji, Ladha Damji, and Tharia Topan, to whose firms the sultans farmed out their customs collection and to whom they were often in debt.

Generation of tycoons

With the advent of British and German colonialism in the early twentieth century, Zanzibar’s commercial power and political influence waned, while the interior of East Africa opened up with new infrastructure and increasing trade. As a result, the Indians spread out all over the mainland, which now consisted of the three colonies of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika. (In 1964 Tanganyika and Zanzibar joined to form Tanzania. The Indians went on to be called “Asians”.) The new generation of tycoons included Sewa Haji Paroo, whose caravans went from Bagamoyo (near Dar es Salaam) all the way north to the Kilimanjaro region. His apprentice, Allidina Visram, topped him to become “the uncrowned king of Mombasa,” supplying the dukas (shops) that had sprung up from Mombasa to Uganda, and further in eastern Congo and southern Sudan. In 1890 A.M. Jeevanjee, a Bohra from Karachi, arrived in Mombasa and made his fortune supplying goods (and workers) to the Uganda Railway. Much of early wood-and-iron Nairobi was constructed by his firm; the city’s Jeevanjee Gardens was his donation.

By the mid-twentieth century every small town in East Africa had the characteristic Indian strip of shops, and in even the smallest village you would find an Indian family branch running the solitary Indian shop. The Asian population totalled 366,000, with the highest number, 176,000, in Kenya with its total population of around 9 million. Unlike elsewhere, Indians had settled in East Africa as communities; there were Bhatias and Khojas, Jains, Shahs, Patels, Lohanas, Sikhs, Bohras, Memons, Kumbhads, and others. In the cities, the larger communities like the Khojas had their own primary and secondary schools for girls and boys, hospitals, dispensaries, and community halls. Dar es Salaam, with roughly 100,000 people at the end of the 1950s, had at least five Asian cricket teams. Abject poverty was rare, and even the most straitened household could afford three simple meals a day. For us growing up in East Africa, it was India that was poor and backward, as revealed to us in the newsreels and Indian films of the period.

Complex and multicultural

East African Asian society was complex and contradictory as any truly multicultural society needs to be (and perhaps as only Indians can make it). Asians tended to live close to their own communities; caste discrimination persisted, as did Muslims sectarian differences. Yet by the standards we see today in the world, East Africans were largely tolerant. It was understood that you did your thing. The azaan would go off in the mosques, the Khoja ginans would blare out over loudspeakers from their jamat khanas, a temple procession would block a road, the Diwali fatakdas would explode in the Hindu sections (and elsewhere). There was hardly any inter-communal violence, and nothing to compare remotely with the communal and caste slaughter that seems so routine in India.

Undoubtedly the Asians were racist — looking up to the “Europeans” and down on the Africans, by whom, as middlemen, they were often resented. Intermarriage between communities and races was a taboo that was just beginning to yield as I emerged from my teen years. Because the poorest people were among the Africans, it has been broadly claimed and often in Shylockian language that Asians were their exploiters. Asian liberals like to wallow in self-guilt. I have often retorted that my widowed mother worked from eight in the morning to ten at night, running her small shop, barely making ends meet while raising five children; whom did she exploit? Today many Tanzanian African women run small businesses similar to my mother’s. We often forget the wealthy and sophisticated African peoples who owned land and cattle; and while many Africans had homes in their villages, most Asians in Africa did not. If Asians did not marry Africans, the Africans, with ancient traditions of their own, had their own taboos; to imply that they panted to lay hands on Asian women is itself racist.

At the end of the 1960s

Be that as it may, around East Africa’s independence, in the early 1960s, there was a thriving community of Asians who saw themselves as Africans. In Tanzania most would speak two Indian languages plus Swahili and English. Among the elite there was excited talk of the “new African Asian” identity. There were Asian politicians and budding writers — Wole Soyinka’s Poems of Black Africa (1975) includes, significantly, three young Asian poets from Kenya; Africa’s most influential and exciting literary magazine of the 1960s, Transition, was founded and edited by Rajat Neogy of Kampala; and Amir Jamal, Tanzania’s beloved minister of finance for many years, was elected in African constituencies. At the end of the 1960s, there was no doubt in my generation that Africa was our home and we were in the vanguard.

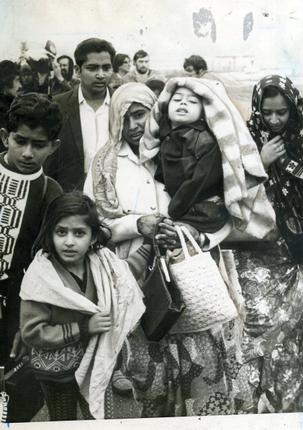

And yet in the 1970s it all fell apart. Kenya’s Asians who had not renounced their British citizenships in time had to leave en masse. In Uganda, Idi Amin had a dream and expelled all the Asians in another “Asian exodus”. In Tanzania, in spite of Nyerere’s enlightened policies, his socialism, combined with the Idi Amin scare, drove out many Asians. What remains of the Asians today is a somewhat insecure and aggrieved population, though most appear dedicated to where they live. Racism of the old sort is gone; intermarriages do happen. At crowded kabab and bhajia restaurants in Dar es Salaam, it is truly pleasing to see Indians and Africans squeezed together at the tables. Indian cuisine has made a big headway especially in Tanzania; country bus stops often have a stand making chapatis; “pilau,” “biriyani” and “sambusa” are Swahili words. What thwarts complete integration is the Asians’ distinct features and cultures, often reinforced by their religious traditions.

A new crop of young Indians has started to arrive. When I see them, they seem foreign and lost. At times I get xenophobic — what are they doing here? do they even speak the language? — when I myself am now Canadian, but also an African Asian.

(M.G. Vassanji is the author of A Place Within: Rediscovering India, and most recently, of And Home Was Kariakoo: A Memoir of East Africa. He lives in Toronto. www.mgvassanji.com)

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Opinion / by M. G. Vassanji / December 27th, 2015