Lucknow, UTTAR PRADESH :

Remembering the prolific Urdu writer from Lucknow whose novels and short stories were full of insights about the lives and concerns of women.

Photo: Mehru Jafar/WFS

The prolific Urdu writer, Begum Masroor Jahan, quietly slipped into literary immortality in her beloved Lucknow on September 22 at the age of 81. Though she left behind an astonishing legacy of some 65 best-selling novels and more than 500 short-stories, the news of the passing of this titan did not even make it to the leading Urdu publications of India, what to speak of English and other languages.

Masroor Jahan belonged to that remarkable generation of Urdu women writers, born between 1925 and 1940, which includes novelists Nisar Aziz Butt, Altaf Fatima, Jilani Bano and Khalida Husain; and the short story writer Wajida Tabassum. With her passing, only two living representatives of that generation remain – Butt from Pakistan and Bano from India.

Born on July 8, 1938 in an educated and literary household in Lucknow, Masroor Jahan’s father, Sheikh Hussein Khayal Lakhnavi, was considered a good poet. Her paternal grandfather, Sheikh Mehdi Hasan Nasiri Lakhnavi, also had a collection of poems to his credit and was the author and translator of many books. Masroor Jahan had a passion for reading stories from an early age.

Her first short-story ‘Woh Kon Thi?’ (Who Was She?) was published in the Qaumi Aavaaz from Lucknow in 1960. Just two years later, she published her first novel Faisla (Decision). She began writing under the pen-name of Masroor Khayal – among others – which she later changed to Masroor Jahan at the advice of her publisher.

From her paternal side, her milieu was feudal, while her father was a teacher and the domestic atmosphere was middle-class. She was married at the tender age of 16 to Syed Murtaza Ali Khan, a nawab. Due to this background, her short-stories portray the minds and matters of all these three classes.

She claimed that whatever she wrote was given to her by her personal experience and observation, and was not fictitious. In a few instances, she even mentioned the real names of people living with her in her novels and when asked about this, pat came the response that she did not fear those folks ever going to court.

Her writings were popular with not only older homemakers but also students. Her stories published in the Urdu journals Beesveen Sadddi and Hareem had a seminal role in the upbringing of Lucknow’s middle-class young women. One of the standards of literary success is also that they be read and liked by every class of society. In that respect, many of her novels went into multiple editions.

Though Masroor Jahan’s forte was the novel, she turned her attention to short stories in the later years of her life and it can be said that the real form of her art is manifested in these tales. The simplicity of her story, the popular manner of writing and easy imagination were the qualities that distinguished her from her contemporaries, including her fellow-Lakhnavi, Naiyer Masud, who passed away in 2017, and Altaf Fatima, who hailed from Lucknow and died in Lahore last year.

Masroor Jahan belongs to the pantheon of female writers like Rashid Jahan, Ismat Chughtai, Quratulain Hyder, Hajra Masroor, Khadija Mastoor, Razia Sajjad Zaheer, Sarla Devi, Saleha Abid Hussain, Bano Qudsia, Jamila Hashmi, Zaheda Hina and Jilani Bano who drew attention to the woman who is present somewhere in society in some form through their short-stories and novels. She witnessed the era of the Progressive Movement as well as that of modernism, post-modernism and other trends in literature, but did not attach herself to any movement or trend.

But while presenting them, she did not adopt the conservative manner particular to some female fiction writers; neither did she adopt the kind of boldness which tramples upon cultural values in the heat of realism.

Whether her topics consist of middle-class or lower-class women, or the Anjuman Aras being nourished in high palaces, or the educated woman of the new society, she always maintained a cautious manner in the presentation of these matters and problems, especially when it came to sexual and psychological tension. She was acutely aware of how the decline of feudalism – when the life of Muslim households of northern India scattered owing to economic and moral decline – made women the ‘altar’ of the false honour of men. She created her stories by making women the subject through small incidents and characters.

Boorha Eucalyptus. Photo: Rekha

Masroor Jahan also wrote romantic stories like the classic Boorha Eucalyptus (The Aged Eucalyptus) from her eponymous collection published in 1982, as well as stories where a helpless woman is hung on the cross of relationships. Then there are women who are the epitome of love and loyalty at one place, but at other places, create problems in others’ lives.

Many novels and short-stories have been written on the debauchery of nawabs and landlords. Wajida Tabassum had become famous at one time for writing such stories. Masroor Jahan too wrote many stories on this topic. But where she made the sexual waywardness of the nawabs her theme, she also presented the positive traits of their character.

In the character of begums too she tried to present every aspect of their life. These stories of a particular milieu express the solitudes and splendours of this culture, whose traces have themselves now become legend.

‘Kunji’ is a classic story of this milieu. Kunji was an extremely beautiful young dancer. Audiences were enthralled by his performances in the nautankis where he presented his dance. People of the highest rank were devoted to his coquetry and beauty. Nawab Zeeshan lost his heart to Kunji. He arranged for the whole nautanki troupe to stay near his harem and gave a beautifully decorated room attached to his bed-chamber to Kunji. In his love for the male dancer, he even forgot the beauty of his begum Anjuman Ara.

Anjuman Ara was amazed at what had happened to the nawab. She was also embarrassed thinking that her rival was not some woman, but a man. Indeed, she herself liked Kunji’s dance; but found her husband’s attachment to him obnoxious. One day when the nawab was off visiting the nearby village, she went to Kunji’s room. The dancer was bewildered by the unexpected sight of a beautiful woman in front of him. ‘I am Anjuman Ara, the begum of Nawab Zeeshan’, she says.

She looks around the room, which had feminine dresses and other articles of feminine adornment everywhere. But the beautiful youth sitting in front of her bore no relation to femininity. His long black hair appeared artificial. She tells him with great gravity that she liked his dance. Despite this praise, Kunji begins to consider himself inferior in front of her. He is also embarrassed listening to praise from her mouth; and he did not have the courage too to look towards her. Firstly, it was the awe of beauty and then that aspect of ridicule in her praise of him which he felt. Despite primping and preening for several hours, he could not compete with this beauty and femininity. People kept encouraging his coquetry now but real beauty was present before him. For the first time in his life, Kunji’s heart beat in a different manner.

He looked at Anjuman Ara with eager eyes. She too was looking in his direction. Their eyes met and lowered. Anjuman Ara’s beauty and femininity had brought to life a man whom the praise and admiration of others had patted to sleep. Anjuman Ara was stupefied reading the message of yearning in his eyes; and worried too. She immediately got up to leave. Kunji too regained consciousness, and said slowly, ‘You’re leaving so soon.’ Anjuman Ara replied, ‘Yes. The nawab will be here soon and then you too will have to change your appearance.’ When Nawab Zeeshan stepped into Kunji’s room upon his return, he saw that instead of the preening dancer he sought, a man was sitting there; and there was a heap of hair before him.

At the point where Masroor Jahan ends the story, looking at Anjuman Ara and Kunji one by one, the reader feels that he has seen with his own eyes how one beauty gives birth to another. Had she wanted, she could have presented Kunji like Ismat Chughtai’s ‘Lihaaf’ (indeed she cited Ismat Chughtai as an early influence and had attempted to make her female characters bolder after the latter’s advice). The nawab of Lihaaf too was happier with boys and left his Begun Jan. But Masroor Jahan did not let Anjuman Ara become Begum Jan. For her, homosexuality was not the refuge Chughtai hinted at for her protagonist.

Unlike ‘Lihaaf’, with which the former was often compared to, Kunji was based on a real-life character. In an interview conducted just five months before her death, Masroor Jahan named Kunji as her favourite real-life character from her stories.

The short-stories of Masroor Jahan with their absent and present realities are those milestones of her creative journey which will not be easily forgotten. About her own stories, she used to say, ‘Actually life is not unidirectional, it has a thousand aspects; and every aspect is a complete world in itself. The fiction writer is a pulse-reader of life. It is her duty to present every aspect of life in its proper context.’

Among the 65 novels she wrote, the social realist Nai Basti (New Colony) is of special interest. Published in 1982, this was topically different from all her novels. Indeed, to my knowledge, this is the first Urdu novel where the problems of nameless city settlements – which are called ‘illegal’ – have been narrated. Premchand had made the rural poor the subject of his novels, but in this novel are the urban disadvantaged, who have their own problems and life – and values that are being trampled on.

I got acquainted with Masroor Jahan barely a month ago when I read Shafey Kidwai’s lucid review of her two recent collections of short-stories namely Naql-e- Makaani (Migration) and ‘Khuvaab der Khuvaab Safar (A Journey Dream After Dream) in the Friday Review of The Hindu.

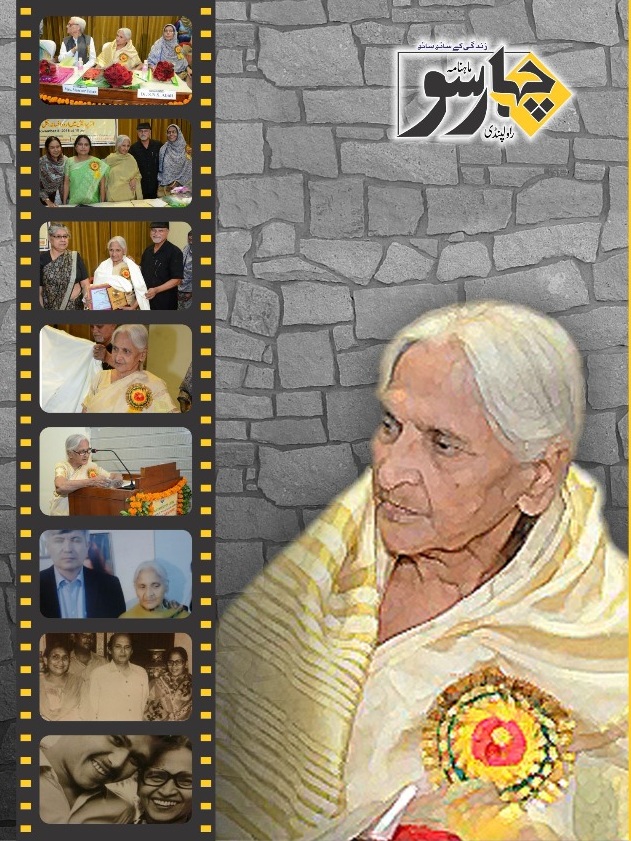

From there, I sought out the January/February issue of the monthly Chahaar-Su, issued from Rawalpindi, which was dedicated to Masroor Jahan and consists of an excellent and quite revealing interview of the writer with the editor Gulzar Javed. These readings also sent me down memory lane to my maiden visit to Lucknow back in 2014 when I was invited to the Lucknow Literature Festival.

It was there too that I made the acquaintance of the lovely and erudite Saira Mujtaba; I sadly do not recall any conversations we might have had with regard to her late grandmother, Masroor Jahan. Now when I think about that visit, I am disconsolate because I know I should have been spending time with the living monuments of Lucknow like Begum Masroor Jahan and Naiyer Masud, rather than admiring the dead buildings of that city. That regret will always be mine!

Masroor Jahan’s quintessential short-story The Aged Eucalyptus talks about the eponymous tree which is a witness to the eras, revolutions, stories and secrets of the haveli where it had stood so proudly for decades in addition to being the recipient of the imprinted affections of the doomed love affair of the two main protagonists, Maliha and Ahmer.

Later on, the aged eucalyptus would provide solace to Maliha as she held it to console herself in her lover’s absence. The story ends with the uprooting of the aged eucalyptus in a storm overnight.

I would like to think that the aged, kind, empathetic eucalyptus was not only a metaphor for the doomed love affair in the story itself but for Masroor Jahan’s own life, patiently accumulating the various sorrows of her life, in which she had to contend with the early deaths of her brother and her son, as well as another brother who went missing in 1973 but never returned (her 1980 novel Shahvar is dedicated to him), and which she never spoke of.

The aged eucalyptus for me also reflects not the physical passing on of Masroor Jahan, but the uprooting of a whole way of life and a system of thinking and feeling which was Lakhnavi culture.

It is now up to her younger successors like Anees Ashfaq and indeed Saira Mujtaba (to whom Masroor Jahan’s last volume of stories Khuvaab Dar Khuvaab Safar is co-dedicated and who is currently translating a collection of her grandmother’s short stories into English) to pen the dirge of Lucknow in our own time.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at: (email protected).

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Books / by Raza Naeem / October 07th, 2019