MUGHAL INDIA :

Rishad Choudhury’s book reveals how pilgrimage transformed Muslim political culture and colonial attitudes towards it, creating new ideas of religion and rule.

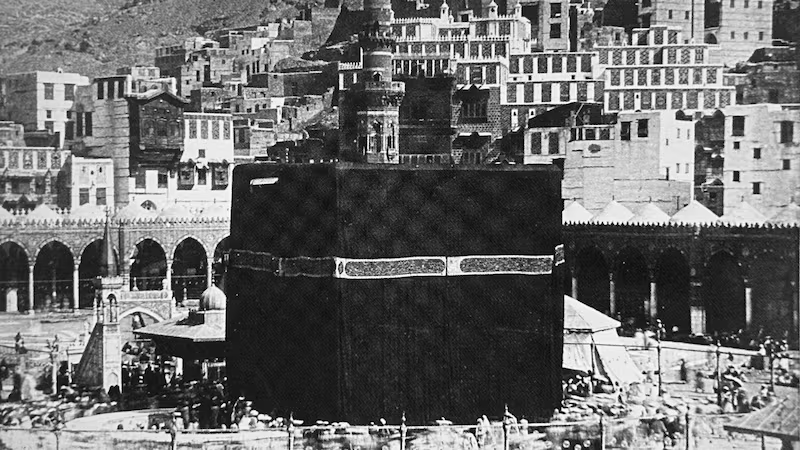

Pilgrims and their ceremonial procession around the Kaaba in Makkah in 1880. Photo: Clu

Every year, Muslims from around the world gather in Makkah for Hajj. Men and women in pilgrim garb circumambulate the Kaaba and perform the sacred rituals enjoined for pilgrims.

But the Hajj is more than a religious gathering. For centuries it was the source of cross-cultural exchanges and trade between Arabia and the rest of the Muslim world.

A new book that sheds light on this is Hajj Across Empires: Pilgrimage and Political Culture after the Mughals, 1739-1857 by historian Rishad Choudhury. It looks at how Islam’s annual pilgrimage changed politics and society in the subcontinent at a time when the Mughal Empire was in decline and as British colonial rule was being established.

During the Mughal rule in India, pilgrims from South Asia were an important source of revenue in the Hijaz, and the Ottoman bureaucracy even referred to the Hajj as “Mevsim-e-Hindi”, the Indian Season. Choudhury writes how “revenues from Indian pilgrims and trade added crucial heft to the imperial treasury”. He adds how they also annually replenished the coffers of the Sharif of Makkah, “who collected half the commercial tariffs at Jeddah”.

Pilgrim vessels from the subcontinent would set sail from Surat, a West Indian entrepot once known as the Bab al-Makkah (Gate of Makkah). It was a cosmopolitan city with reports of Arab, Persian and Turk traders and emigres being there into the late 18th century. The Mughals built lodgings and infrastructure to help pilgrims in the city. Later, during British rule, Surat lost its status to other port cities like Mumbai and Kolkata.

While the patronage of Hajj has a long history in the subcontinent, Choudhury writes that it was under the 16th-century Mughal emperor Akbar that organised pilgrim movements from north India began.

British sponsorship of the Hajj

When the East India Company began to take over the subcontinent, it didn’t initially get involved with the Hajj. However, several developments led it to eventually administer the Indian pilgrimage to Makkah. One key turning point was Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, which triggered greater British interest in Middle Eastern politics and the need to keep an eye on the Indian Ocean against potential invasions. Sponsorship of the Hajj also allowed the British to lend their colonial rule an air of legitimacy.

Choudhury details how local royals, particularly women, would make appeals to the British for allowances to travel for Hajj.

“Despite their royal status, in the end, the colonial state and Indian rulers alike regarded women’s immobility as necessary to preserving order in aristocratic households,” Choudhury writes.

In the region of Awadh (northern India), for example, the rulers repeatedly attempted to frustrate the plans of noblewomen seeking to leave for Makkah as pilgrims, writes Choudhury. He adds: “Particularly stringent controls were placed on begums who happened to be beneficiaries of the British.”

Among those petitioning the British was Saiyid-un-Nisa, a widow of Tipu Sultan, the 18th-century post-Mughal ruler of Mysore who was killed in battle with the British.

She wrote a long letter to the East India Company detailing her circumstances and requesting permission to travel to Makkah for pilgrimage.

Then there was the Mughal courtier Munir-ud-Daula, who also tried to leave for Hajj with a request to the British but failed to win the emperor’s permission and was “dissuaded” from the trip by the British after they were approached by the Mughals.

Under the ruse of protecting Hajj vessels from India, the British justified the conquest of the Yemen capital Aden in 1839, as it summoned a casus belli after an alleged assault, by a “crowd of Arabs” on another Hajj vessel, the Darya Daulat.He adds: “The British in this instance specifically also cited the need to protect royal Indian women going on Hajj, as the Darya Daulat was the property of a princess from Arcot.”

Hajj Across Empires is not a book about the theological or spiritual specifics of the Hajj itself. Rather it is in part an anthropological study of Indian pilgrims grappling with the decline of the Mughal Empire, and its successor states, as British colonialism took hold in their homeland.

While religious developments and changes from the era are generously described in the text, it is more about networks of Sufis and the different interpretations of Islam being imported from Arabia by pilgrims.

However, the book suffers from the use of too many words, and simpler vocabulary may have brought clarity to Choudhury’s otherwise thoughtful analysis. This may have helped the book, which is due for release this month, reach a more mainstream readership.

Also, the book’s themes do not feel very tightly connected, with the range of issues including the bazaar economy of the Hajj, imperialism, diplomacy and localised cults of shrine pilgrimage within the subcontinent. Readers are at risk of losing the thread at times.

However, it’s an important addition to literature on the topic, even if the niche subject matter will probably only appeal to academic readers.

Hajj Across Empires: Pilgrimage and Political Culture after the Mughals by Rishad Choudhury will be published this month

source: http://www.thenationalnews.com / The National / Home> Culture> Books / by Syed Hamad Ali / January 01st, 2024