JAMMU & KASHMIR :

The period between 1371 and 1405, during the initial days of the Shahmiri Sultanate, was extremely crucial in Kashmir’s transition to Islam. It witnessed the arrival of Amir-e-Kabir, his son and their 1000-odd followers who joined a more than 200-year old campaign for Islam in a Hindu state. How these 33 years changed Kashmir forever is one of the fascinating stories of Kashmir’s quantum jump in faith and mobility, reports Masood Hussain

Noble of nobles, commander of Persia;

whose hand is the architect of the nations;

Ghazali himself learned the lesson of Allah is He;

and drew meditation and thought from his stock;

Guide he of that emerald land, counsellor of princes, dervishes, and Salatin;

A king ocean-munificent, to that vale, he gave sciences, crafts, education, religion;

That man created a miniature Iran, with rare and heart-ravishing arts,

With one glance, he unravels a hundred knots

rise, and let his arrow transfix your heart.”

Allama Iqbal on Shah-e-Hamadan in Javid Nama

Involving the reign of four Sultans, the history of Islam in Kashmir had a vital three decades that went into shaping the society as it is known today. This period begins with Shah-e-Hamadan visiting Kashmir in 1371, and concludes with the emigration of his son Mir Mohammed Hamadani from Kashmir in 1405. This period also witnessed the emergence of Sheikh Noorruddin Noorani, Kashmir’s bearer saint, and Lal Ded, one of Kashmir’s most popular woman ascetics, whose campaign against idolatry is unprecedented in Kashmir history.

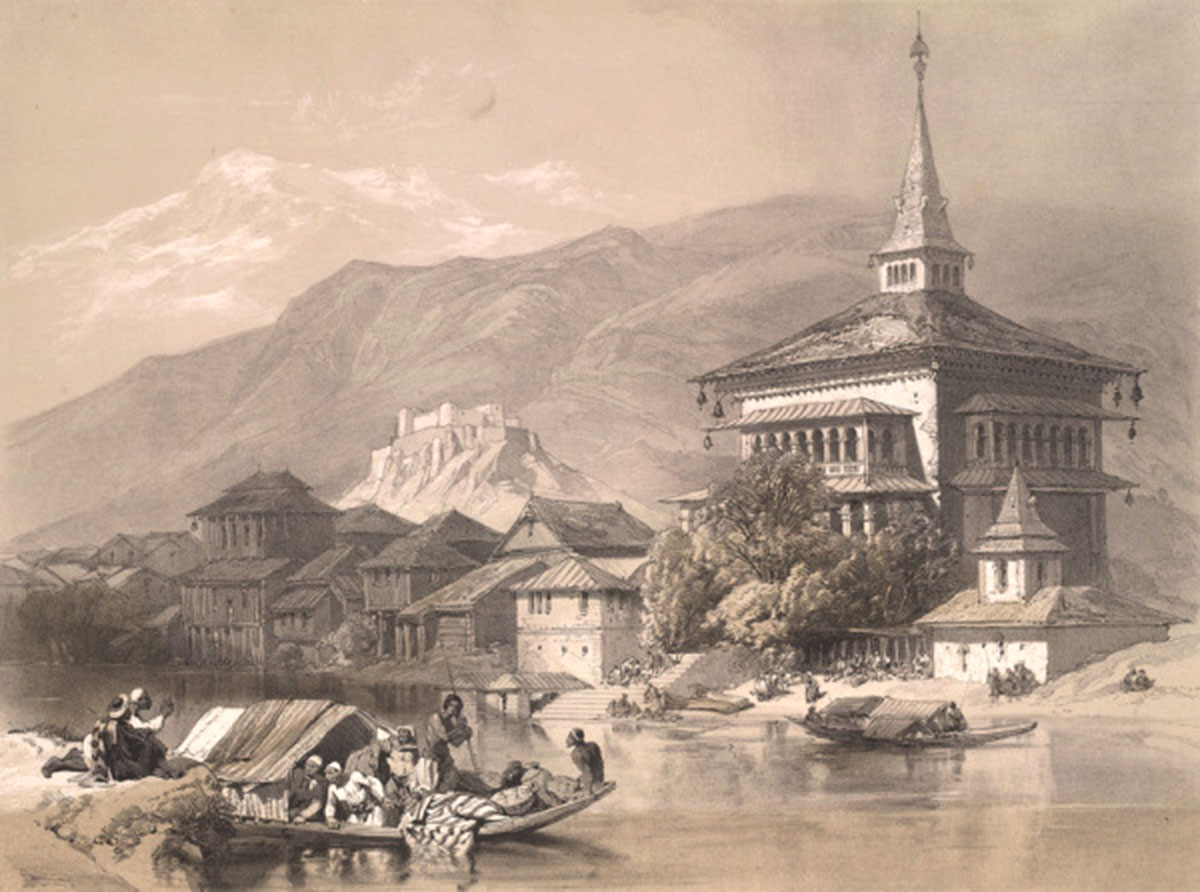

This period falls in the first phase of Kashmir Sultanate that Shahmir built in 1339 over the ruins of a Hindu empire. The Sultanate lasted around 191 years till 1530. Muslim rule was actually established by Ladakhi prince Rinchan, who effortlessly took over a headless, mourning Kashmir in 1320 after Dulchu wrecked the Vale. Three years later, a Hindu king succeeded him for five years but the administration was controlled by Shahmir family, who eventually founded the Sultanate.

What makes this period distinct is that faith started interrupting the power politics at a time when Kashmir was still a Hindu majority state with Muslim chunks in army and administration. Mir Syed Ali Hamadani and his son Mir Mohammad Hamadani were the two major players behind these interventions. This was perhaps because Shah-e-Hamadan, the most respected Islamic scholar of his time, came from Hamadan’s ruling family. His father was the city governor.

Even though the number of visits Amir-e-Kabir made to Kashmir has divided historians, it is generally believed that he came for four months in September 1372 and then left for Mecca. He then returned in 1379 to stay for almost two and a half years. His last visit to Kashmir was in 1383 and he stayed for almost a year.

“The most credible sources of the particular era talk of only one visit of the Amir,” Prof M Ashraf Wani, the author of Islam in Kashmir. “There is, however, a dispute over the duration of the visit between 80 days and six months.”

Historians perceive his last visit as the most consequential one since he led 700 people from Hamadan to Kashmir who eventually began working as missionaries and preachers, after settling in the valley. More than faith, they spearheaded a socio-cultural transformation of Kashmir.

Amir’s Migration

Amir-e-Kabir belonged to Alawi Sayyids who were facing problems due to Timur’s Iran takeover. Timur disliked the Sayyids who knew that circumstances may force them to migrate. In anticipation of his visit, Amir sent his cousins to Kashmir to explore if it was hospitable for missionary work, and possibly migration. The first cousin was Sayyid Tajuddin, who came in the reign of Sultan Shahabuddin (1354-73). The king built a Khanqah for him in Shahabuddin Pora in Srinagar and, according to historians, assigned revenues from Nagam village for the hospice’s maintenance. The Sultan visited him frequently. On his insistence, Tajuddin opened a few Darsgahs where Hadith and Fiqah were taught.

Later, Tajuddin invited his brother, Syed Hussain Simnani, who had already migrated to Delhi, to Kashmir along with his family and they settled in Kulgam. On his hand, Salat Sanz, Sheikh Noooruddin Noorani’s father converted to Islam. Syed Tajuddin is buried in Awantipore.

Amir followed his cousins to Kashmir. It was September 1372 and Shihabuddin was ruling Kashmir. But the Sultan was out, probably on an expedition against king of Ohind (now Attock Khurd), and Qutubuddin, in-charge ruler, writes Muhib-ul Hasan in his Kashmir Under the Sultans, went out with his chief officials and received the Amir with great warmth and respect, and brought him and his followers to the city. He started living in Alauddin Pora where a Suffa, a raised floor, was built for his prayers, which the Sultan would usually attend.

After staying in Kashmir for four months, the Amir left, and, according to G M D Sufi, the author of Kashir – Being a History of Kashmir, he visited the battleground and brought reconciliation between the two Muslim rulers.

It was his next visit in 1379 when Sultan Qutubuddin personally received him. Amir stayed for two and a half years, the longest of his three sojourns in Kashmir.

Then, kings were Muslims but the majority of the subjects were Hindus. Beliefs had changed but the customs and the traditions of the neo-converts were rooted in Hindu culture. Qutubuddin would wear the typical Hindu elite dress; perform a yagna to avert a famine, go to the Alaudin Pora temple every morning along with Muslims and had two sisters in his harem. Amir intervened. The Sultan divorced the older of the two sisters he had married, remarried the younger one in Islamic tradition, and started using the Muslim nobles dress.

Limited Intervention

A great scholar, Amir-e-Kabir would write in Persian and Arabic on a variety of subjects. He has authored nearly 170 books in his life. The manuscripts of around 20 of his Rasails are preserved in Oriental Research Department, Srinagar, according to Mohammad Hayat, who has extensively worked on Hamadani’s religious thought as part of his doctorate.

Historians have specially mentioned his Zakhirat-ul-Malook, a collection of his thoughts about routine life, politics, governance and the statecraft. Amir’s idea of Muslim rulers was that they should not be pleasing-all, dishonest, haughty rulers who would appoint cruel tax collectors or draw peoples’ attention by force and ignore ulema. He wanted them to be just and benevolent rulers who would address the needs of the Muslims before offering prayers, follow the Caliphs in dress and food, are polite with subjects, have a strong sense of good and bad, keep promises, and respect elders.

The Amir put the subjects into Muslims and Kafirs and gave the Muslim subjects 20 rights. Listed by Darakhshan Abdullah in Religious Policy of the Sultans of Kashmir (1320-1586), the Amir disliked the Muslim ruler listening trivial things against Muslim subjects or unnecessarily peeping into their faults. He wanted the ruler to pardon smaller offenders, avoid entering into Muslim homes without permission, not treat a wicked and civilised at par, encourage the rich to send poor on Haj on their behalf, take care of the poor, set up robber-free roads, lay bridges, build mosques, appoint Imam’s and pay them for their services, and implement lawful and prevent unlawful.

The book included a set of 20 rules about how the Sultan should handle zimins. Invoking an agreement of the Caliph Omar bin Khatab, the Amir wanted the Muslim ruler must disallow non-Muslims construction and repairing of temples, living near Muslims, burying their dead in Muslim graveyards, mourning loudly over a death, imitating Muslim dress, taking Muslim names, riding any house with saddles and bridles, putting swords, arrows and bows, exhibiting their rituals to Muslims, or using signet rings. Hindus, according to this doctrine, required a distinct dress, could not take a Muslim slave, or disrespect Muslims.

Not Delinked From Politics

“One of the significant contributions of Hamadani was, despite being a Sufi, he did not set himself aloof from politics or the government,” Mohammad Iqbal Rather writes in his doctoral thesis A Study of Islamic Political Thought of Mir Syed Ali Hamadani (1314-84). “He, apart from writing on political affairs of state, personally established contacts and wrote letters to the rulers of Kashmir for enlightening them with Islamic teachings and Shariah rulings, particularly regarding state affairs.”

Sultan Qutubuddin would routinely attend his sermons in Srinagar. Still, he received a letter from the Amir, possibly from Pakhli. “If the tempters lead the unbelievers towards evil, it is not surprising. What is surprising is that Muslims are running away from the true path in spite of God’s warning,” the Persian letter translated by A Q Rafiqui in his Letters of Mir Syed Ali Hamadani, reads. “Out of sheer love, I advice you that the worldly glamour is like a fast wind and the worldly favour is like an unfulfilled dream; He alone is wise who neither gets fascinated by dreams, not feels proud of any notion but learns a lesson from the experiences of bygone people, believing firmly in the axiom that ‘one who does not learn the examples of others, himself becomes an example for others’”.

“Hamadani, uniquely opines that a just ruler must be accompanied by a ‘Sufi reformer’ who would keep a check on the rulers,” writes Rather. “He suggests that the Sufi reformer should assist the ruler to keep the society free from injustice and rebellion and should always guide him in implementing the laws of Shariah. At the same time, Hamadani lays stress on the economic autonomy of the Ulama so that they may not work under the influence of the ruler and dictate the laws according to the wishes and whims of the rulers.”

“Anxious not to antagonise his non-Muslim subjects, Qutubuddin did not follow every advice of the Sayyid, but he held him in great reverence, and visited him every day,” Muhibul Hassan writes. “Sayyid Ali gave him a cap, which, out of respect, the Sultan always wore under his crown.” The Amir has not accepted any monetary help or royal gifts and is recorded to have earned his livelihood by making Kullah caps, one of which he had gifted to the king. He had stayed in a Saraie and not the palace. In his Sufism in Kashmir (14th to 16th Century), historian Dr Abdul Qayoom Rifiqui concludes: “Sayyid Ali’s political thought was altogether theoretical and had no bearing upon actual practice.”

Facilitating Faith

Sultans had the power at the core of their priorities. So they disagreed with the preachers on many counts. But they never stopped facilitating the preachers in spreading Islam. Many think that the thousand-odd Sayyids came as a sort of state-supported intervention in the spread of Islam in Kashmir that, till then, was organic. Every single migrant-preacher deployed on ground by the Amir was extended some sort of support by the Sultanate in Srinagar. Various Khanqahs were set-up and revenues from specific villages were assigned to their upkeep.

Some of the most prominent of the Amir’s followers were Sayyid Kamaluddin, the preacher whom Sultanate retained for guidance when the Amir decided to leave Kashmir. There was Sayyid Muhammad Kazim, aka Sayyid Qazi, Amir’s librarian (Lethpora), Sayyid Kabir Baihaqi (Srinagar), Sayyid Muhammad Balkhi aka Pir Haji Mohammad Qari, the scholar who would teach the royal family, lived and is buried in the Khanqah that history knows as Langherhat (Srinagar), Sayyid Mohammad Qureshi and Syed Abdullah, who were stationed in Vijayesvara (now Bejbehara), Sayyid Fakhruddin and Sayyid Rukunuddin (Avantipore).

The Sayyids’ entry came at a time when the ground had slipped away from Hinduism, and the situation was ripe for a change. Lal Ded, Kashmir’s most known acetic was Amir’s contemporary. She is recorded to have met his cousin in Kulgam.

“Men were intolerant, depraved and vicious, and women were no better than they could make of them,” Dr R K Parmu writes in A History of Muslim Rule in Kashmir (1320-1819) explaining how Lal Ded’s poetry ripped the society apart. “The people were generally made to believe in occultism, in magic, in stocks and stones, in springs, in rivers, in fact, in all the primitive forms of worship.” Parmu has written that the ascetic openly preached against this kind of worship. “The stone in the temple, she says, is no better than a millstone or the stone in a pavement,” Parmu wrote. “The idol is but a lump of stone and the temple the house of this lump.”

The rebellion within the caste-ridden society opened the doors for Islam.

“She preached harmony between Hindu Vedantism and Sufism,” Fehmida Wani writes in her excellent study The Search for Shared History of Mankind: A Case Study of the Technological and Cultural Transmission from Persia and Central Asia to Kashmir. “It benefited in the process of conversion.”

Sayyid Impact

With the state apparatus supportive and the society willing to change, how the immigrant Sayyids used the situation for Islam’s spread is something that historian may have to find answers for. So far, the narratives that have emerged in the last more than 600 years revolve more around ‘miracles’ and legends of the privileged preachers.

Islam, it needs to be mentioned, existed in Kashmir more than 200 years before the Ladakhi prince converted at the hand of Hazrat Sayyid Sharfuddin Abdur Rahman, the Bulbul Shah, in 1320. However, what was visible was that converts were rooted in the culture they had come from. That is perhaps why Tarikhi Kashmir insists that the Amir “cleaned the mirrors of the hearts of the converts of Kashmir from the rust of darkness by showing them the right path.”

Written by Sayyid Ali in 1579, historians see Tarikh-i Kashmir as the first Persian chronicle that details the migrations of the father and son along with 1000-odd murids who contributed in Islamising Kashmir culture.

Amir’s followers and disciples had come from the cradle of Muslim civilisation. Men of letters, they came with improved crafts and a sense of politics and history. Amir himself was a master Sozan Kar, a poet, an impressive prose writer and thinker. With access to the ruling structure, having some sort of economic tools in hand and logical explanations to the issues of faith, Sayyids obviously had an impact on the ground. They changed the culture forever.

The Aurad

Prof Mohammad Ishaq Khan, however, sees the situation differently. “It seems that Sayyid Ali’s stay in Kashmir was brief, not extending beyond one year. During this period, he remained the royal guest and, as such, his activities remained mainly confined to royal circles. He imparted lessons to the Sultan on God’s commands about the good works and evil,” Khan assesses in his magnum opus Kashmir’s Transition to Islam. “Besides engaging in some missionary activities in Alauddinpura and around the capital, he does not seem to have established any mass contacts. One wonders how, in view of the language barrier, a Sufi scholar like Sayyid Ali, would have made the esoteric as well as the exoteric version of Islam, as given by him in a plethora of works, intelligible to the Kashmiri masses.”

Khan, however, sees Hamadani’s major contribution in the Aurad-i-Fatḥiyyah. A grand mix of prayers, the praises for God, excerpts from the Quran, this Aurad has been an essential morning recitation in mosques for nearly 700 years now. It was Amir’s response to the pleas of neo-converts that the temple rings disrupt their morning prayers and they need something for loud joint recitation, something they had been doing for ages as Hindus. Khan sees it as “local influence” and “assimilation of the local mode of worship in the Islam of Kashmiris”.

“Islam, in no small measure, owes its success to his remarkable role which was distinguished by his tolerance towards the Kashmiris’ penchant for singing hymns aloud in temples,” Khan wrote. “The sight of a small number of people professing faith in Islam and simultaneously going to temples must have caused a great deal of concern to Sayyid Ali. But it goes to his credit that instead of taking a narrow view of the religious situation in Kashmir, he showed an acute discernment and a keen practical sense in grasping the essential elements of popular Kashmiri religious culture and ethos, and gave creative expression to these in enjoining his followers in the Valley to recite Aurad-i Fathiyya aloud in a chorus in mosques”

As the neo-converts chanted the Aurad, even the Hindu court historian Srivara was impressed: “It was here that the yavanas (Muslims) chanted mantras and looked graceful like the thousand lotuses with humming bees.”

But Ashraf insists that Amir’s contribution was in laying the foundations for the institutions of Islam in Kashmir. “Islam was spreading gradually before him and took a long time after him as well,” Ashraf said. “But the institutions of faith in Sufi systems were set up by him and his disciples.”

Departure

“After Sayyid had been for about a year in the Valley, he decided to leave,” Hassan writes about Amir’s eventual departure in 1383. “The sultan tried to persuade him to postpone his departure, but Sayyid refused, and departed with some of his followers, leaving behind Moulana Mohammad Bulkhi commonly called Mir Haji Mohammad, at the request of the sultan, to give him guidance in matters relating to the Sharia.”

Did the Amir leave because he was unhappy with the Sultan, who would still go to the temple and meet the Brahmins. “As chronicler Sayyid Ali (Tarikhi Kashmir) points out “a large majority of his subjects were kafir and most of his officials were polytheists” so for maintaining a cordial relation, he considered it necessary to follow such a policy,” writes Darakhshan. “It was on this ground that Qutubuddin did not follow every advice of Sayyid Ali regarding state matters. Dissatisfied with Sultan’s response to his directives, Sayyid Ali decided to leave Kashmir. He left via Baramulla with the intention of performing the pilgrimage.” Another contemporary history, Baharistan-e-Shahi also points out that Sultan could not oblige the Amir by implementing the Shariah.

Ishaq Khan, however, says that his departure was not the outcome of the alleged conflict with the Sultan. Amir had written favourably to the king, even after his departure. “Notwithstanding Sayyid Ali’s emphasis on following the Sharia, he seems to have allowed practical wisdom and expediency to guide him in his attitude towards the Sultan’s non-Muslim subjects in Kashmir rather than the model he had chosen in his general work for a Muslim Sultan to follow,” writes Khan. He continued writing letters to the Sultan. In one, he praised a devote Brahmin. “In another letter sent to the Sultan from Pakhli, Sayyid Ali urged him to leave no stone unturned in popularizing the Sharia, but only within the possible limits.”

But, at the same time, it was also a fact that Amir’s letter indicated the spread of Islam in Kashmir was still a work in progress. “Our souls can never live in peace and tranquillity even if all (our) ambitions get fulfilled,” the Amir wrote to Muhammad Khawarazim, who he had left in Kashmir. “But it is really surprising that how can one ever live peacefully in the land of infidels or feel contended where the wicked flourish and are provided support!”

(This is first of the three-part series on the socio-economic impact of the immigration of more than 1000 preachers and professionals that Amir-e-Kabir Mir Syed Ali Hamadani led to Kashmir during the initial years of the Kashmir Sultanate.)

source: http://www.kashmirlife.net / Kashmir Life / Home> Cover Story> Faith / by Masood Hussain / May 22nd, 2019