Dharwad District, KARNATAKA :

Abdul Khadar of Karnataka was awarded by the National Innovation Foundation for developing the device.

Villages in rural India are not just about farming and growing crops. They house some brilliant scientists and innovators who might not have the required technical qualification but through personal experience have learnt the art of developing a device or machine that can help them overcome their manual drudgery.

In fact, there are several such innovators housed in some remote corners of this county’s villages that the scientific fraternity has failed to recognise.

This could perhaps be because, technically, they are not qualified or the findings do not fall within their circumference of activities. Nevertheless, rural India’s brilliant minds continue to develop and find answers in its own way rather than depending on others for an answer.

The credit for recognising these rural innovators and helping them showcase their findings should go to the National Innovation Foundation (NIF) in Ahmedabad, which under the able leadership of professor Anil Gupta and his team, has been maintaining a database of thousands of such findings, new discoveries and lost ancient practices, bringing them into the limelight.

Every year, the government of India hosts a function at Rashtrapati Bhavan for these people through the foundation to encourage and throw more light on their inventions so that the common man can understand rural India better.

Awards are conferred on many of these rural innovators, with the president of India himself attends the function and gives the awards.

In fact, NIF has gone a long way in changing society’s perception of rural India. They have managed to change the perception of rural India as only about and for farmers to one of innovation.

Take the case of Abdul Khadar from Karnataka’s Dharwad district, whose innovation was recognised by the NIF.

Khadar is from an agrarian family. Last year, his lands were dry throughout the year.

Since he was dependent on the annual monsoon, which was playing truant, he decided to plant fruit trees like mango, sapota and jujube, intercropping chilli in between so that he could get income in a short time. But owing to the acute scarcity of water, the idea failed.

In search of a crop that could grow in dry areas without needing much attention, he learnt that tamarind trees fit the criteria well. Huge tamarind trees planted on highways, uncared for yet with lush green canopies caught his eye.

Since the mid 1980s, he has planted nearly 2,000 tamarind trees on his land. Not only have the plants survived, they have also grown well. The success of growing tamarind with scarce water was an innovation in itself.

Khadar also sunk 11 bore wells to try to get some water but only two of them worked. He spent nearly Rs 2 lakh in the process.

In an attempt to make his land more fertile, he dug six small ponds to harvest rainwater. “After monsoon, water from the bore well was used to pump into the ponds. The water was then used for flood irrigating the plants,” said Vipin Kumar, the chief innovation officer at NIF.

Khadar constructed underground tanks to preserve the tamarind pulp. According to him, pulp preserved in such a manner had a long shelf life and could retain the original quality and flavour for a longer period.

Until now, value addition in tamarind is rare, but Khadar wanted to try something new. He began by manufacturing pickles and jam, which is marketed as far as Hyderabad.

He also thought of another new experiment when he faced problem in making pickles. The process of making pickle was labour intensive and tedious as one had to first harvest tamarind from the trees and then separate the fruit from the pods manually (similarly to groundnut). He conceived a unique technique for harvesting tamarind from the trees but did not go ahead due to the high cost involved.

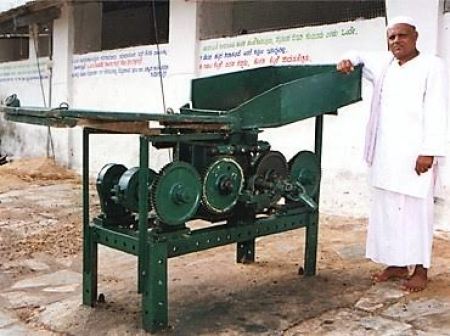

“After spending about Rs 3 lakh and six months of hard and intensive labour I finally developed a machine to separate the tamarind seeds. It had a system wherein the seed gets thrown out of the tamarind pod,” he said.

The next step in pickle making was to cut the unripened tamarind into small pieces. For this also he developed a machine for slicing tamarind fruit into tiny pieces. “The machine serves multiple purposes and can do the job more efficiently and effectively,” he explained.

Through the support of the Karnataka government, many of his products are available to farmers at subsidised rates. Khadar’s innovation has been documented by the NIF, Ahmedabad.

Vipin Kumar, chief innovation officer, National Innovation Foundation, Ahmedabad: vipin@nifindia.org, 9825316994.

source: http://www.thewire.in / The Wire / Home> Agriculture / by M. J. Prabu / April 06th, 2017

what is the cost of tamarind seed separation mechine and please send the list other machine available may be informed to following mail.id