INDIA:

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s name is taken with great pride and respect in Maharashtra. Every year on February 19, Shivaji Jayanti is celebrated with great pomp across the state. The coronation day of Shivaji Maharaj is also celebrated on June 6, 1674. About 350 years ago, Shivaji Maharaj was coronated at Raigad Fort in the presence of thousands of people.

There have been many kings but people remember only those who worked for the good of the people. Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj is one of them as he established Swaraj based on the values of equality, brotherhood, and justice. During his rule, he worked for public welfare without any discrimination.

These days, Shivaji Maharaj is portrayed as a Hindu ruler by vested interests like political parties and organizations. Is it fair to see a great personality like Shivaji Maharaj only in the frame of religion? To see Shivaji Maharaj only as a protector of religion amounts to diminishing his stature. Shivaji’s life was spent following high ideals.

He respected Saints, Peer Auliyas, and all religions. For this reason, when he established Swaraj, along with the local Marathas, a large number of Muslims also supported him. At that time the Marathas who were in his army were called Mawle of Shivaji. Thousands of Muslims participated in the battles he fought; his administration also had Mawle. That is why even today Muslims of Kolhapur, Satara take part in Shivaji Jayanti processions with great fanfare.

During the rule of Shivaji Maharaj, public welfare, justice, and brotherhood were given priority. That’s why he and his regime are remembered even today.

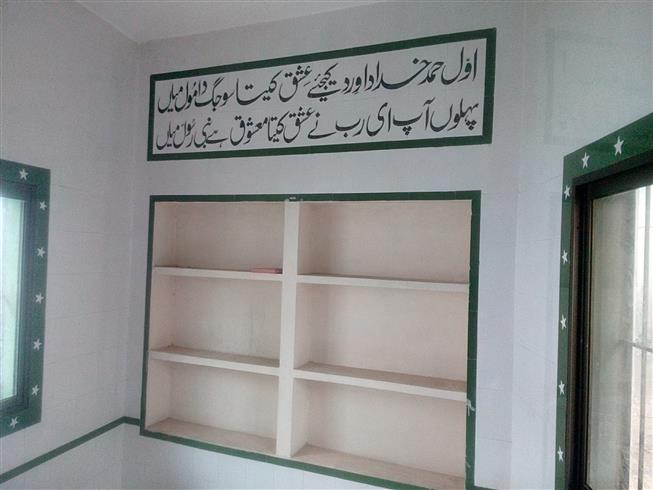

Shivaji Maharaj’s family respected Sufi saints a lot. His grandfather had named his two sons Shahji and Sharifji after the Muslim Pir Baba Shah Sharif. Shivaji Maharaj had great respect for Sufi Saint Baba Yakut. Before leaving for the war front he visited Baba to seek his blessings. He also had oil lamps lit on various dargahs, the resting place of the Sufis.

Women were respected during Shivaji’s reign. Even during the war touching a woman was prohibited. It seems that after the governor of Kalyan was defeated at the hands of Shivaji’s forces, his beautiful daughter-in-law was presented to Shivaji. He was ashamed of his General’s act of using a woman as a booty. He apologized to the Muslim woman and told her she is like his mother and returned her to her homeland with full state honour.

Shivaji Maharaj had unwavering faith in his Muslim soldiers. There were more than 60 thousand Muslim soldiers in his army. He had also established a strong Navy and its command was in the hands of Muslim soldiers. Even the management of sea forts was entrusted to experienced Muslim governors like Darya Sarang, Daulat Khan, Ibrahim Khan, Siddi Mistry. Many Muslim warlords like Rustamozman, Hussain Khan, Qasim Khan left the princely state of Bijapur and joined the army of Shivaji Maharaj along with 700 Pathan soldiers. Siddi Hilal was one of the closest Sardars of Shivaji Maharaj. His acts of bravery in the war are famous.

Most of the cannons used in Shivaji’s army were manned by Muslim soldiers. Ibrahim Khan was the chief gunner; Shama Khan and Ibrahim Khan were the head of the Cavalry squad. Siddi Ibrahim was one of Shivaji’s bodyguards. In the encounter with Afzal Khan, Siddi Ibrahim saved Shivaji Maharaj by risking his life. Later, Shivaji Maharaj appointed him as the head of the Fonda fort. All the facts bear testimony to a close bond between Shivaji and his Muslim associates.

When Shivaji was under arrest in Agra Fort, a Muslim man named Madari Mehtar played the most important role in his escape. While Shivaji escaped from the fort, Mehtar masqueraded as him.

With his secular ways, Shivaji Maharaj won the hearts of his colleagues and they were ever ready to make sacrifices for their king.

Qazi Haider, a scholar of the Persian language was Shivaji’s Chief Law officer. He had a major role in the administration’s correspondence and agreements and secret plans. Once a Hindu Sardar expressed doubts about Qazi Haider and advised Shivaji against trusting him. Shivaji told him rather curtly: “Honesty is not tested by looking at someone’s caste (religion), it depends on that person’s deeds”.

The preparations for the coronation of Shivaji Maharaj had started long back. New buildings including temples were being constructed when Shivaji Maharaj reached Raigad to review the work. On his return to his palace, he asked his Sardars while they have built magnificent temples why no mosque for Muslim subjects has been built. Immediately, a mosque was built right in front of the palace and it stands there even today.

Today the rivalry between Shivaji and Afzal Khan is presented as a story of Hindu-Muslim tension. The truth is after Afzal Khan died, Shivaji Maharaj ordered that his body be buried with Islamic rites. A concrete grave was built for Afzal Khan; his sons were pardoned.

Such behaviour of a ruler against his enemy is rarely found in history.

All these incidents of history prove that the war between Shivaji Maharaj and the Mughals was of mutual conflicts between the kings for political interests and not for religious supremacy.

source: http://www.awazthevoice.in / Awaz, The Voice / Home> Story / by Mukhtar Khan, ATV / posted by Aasha Khosa / February 22nd, 2023