Rampur, UTTAR PRADESH:

Was the adrak halwa truly created for an ailing Nawab? Determined to find the origins of the halwa, food researcher Tarana Khan looks for clues in Rampur’s libraries, kitchens and at a local halwa festival.

We needed to cook adrak halwa urgently before publishing it in our series on forgotten foods for Scroll.in. Pakistani writer Muneeza Shamsie had inherited the sweetmeat recipe from her parents’ cooking diary, and added it to an article on her family’s gastronomic journey from Rampur to Karachi. The recipe required three straight hours of cooking. But since there was a shortage of gas supply in her country, I—as the curator of the series—gallantly stepped in. My old cook Akhtar bhai and I could take turns to stir and sauté the halwa. I was curious about the roots of adrak halwa,a specialty of my hometown Rampur.

Muneeza’s mother, Jahanara Habibullah, was the sister-in-law of Nawab Raza Ali Khan (ruled 1930-1949), and had experienced the best culinary traditions of the famed Rampur royal dastarkhwan. She had written in detail about the cuisine in her memoir, Remembrance of Days Past: Glimpses of a Princely State During the Raj. Their household in Karachi had two Rampur khansamas (male chefs), Sabir and Amjad, who had transported Rampur’s culinary traditions to Pakistan. The recipe for adrak halwa was adapted by Muneeza’s gourmand father, Isha’at Habibullah, from the cooking techniques of the two khansamas.

But adrak halwa no longer appears at our dining table during winter. The image of adrak halwa being cooked for my grandfather and set in a silver bowl from which Nana Abba took a spoonful on cold winter mornings is probably a family memory that predates my childhood. In fact, I don’t remember ever eating it as a child.

Culinary wisdom—which I must have accessed through collective memory—dictated that October, the month of tender ginger shoots, was the best time to cook the halwa. Muneeza’s recipe called for an elaborate list of ingredients, and a painstaking procedure which began with soaking the shoots overnight, and grinding it thrice on the sil-batta with some milk.

I conserved manpower, aka Akhtar bhai, for sauteing while I used the mixer grinder. The ginger paste needed to first be put through a sieve to remove the fibres, and then cooked in milk, ghee, and cream till it was thick enough to drop from a spoon. The real work began when we added sugar, and sautéd it to a deep golden hue. It took an hour of vigorous stirring for the ghee to separate from the halwa, and form a thick glistening layer. I unscrupulously drained it by half.

I tested the halwa on my unsuspecting cousin and his non-Rampuri wife. The wife curled her lips, and said she’d never had a more obnoxious sweet dish. My cousin asked for a second helping. I loved the halwa, but it had a sharp, spicy and gingery aftertaste that clung to the back of my throat. My husband said it tasted like hakim’s majoun (medical concoction), and that I should have sautéed it more; he remembered a darker adrak halwa being cooked in his ancestral home. I gritted my teeth, smiled, and told him to join us in sauteing the next time we prepared the halwa.

Muneeza’s recipe called for an elaborate list of ingredients, and a painstaking procedure which began with soaking the shoots overnight, and grinding it thrice on the sil-batta with some milk.

His comment also amused me, though. Citing a blanket oral history, several articles and food blogs mention that the halwa was devised by the Rampur khansamas when a Nawab was advised by his hakim to eat ginger for knee pain. The Nawab, who hated ginger, was surreptitiously fed the halwa, and grew fond of it. Always a curious food researcher, I decided to dig deeper.

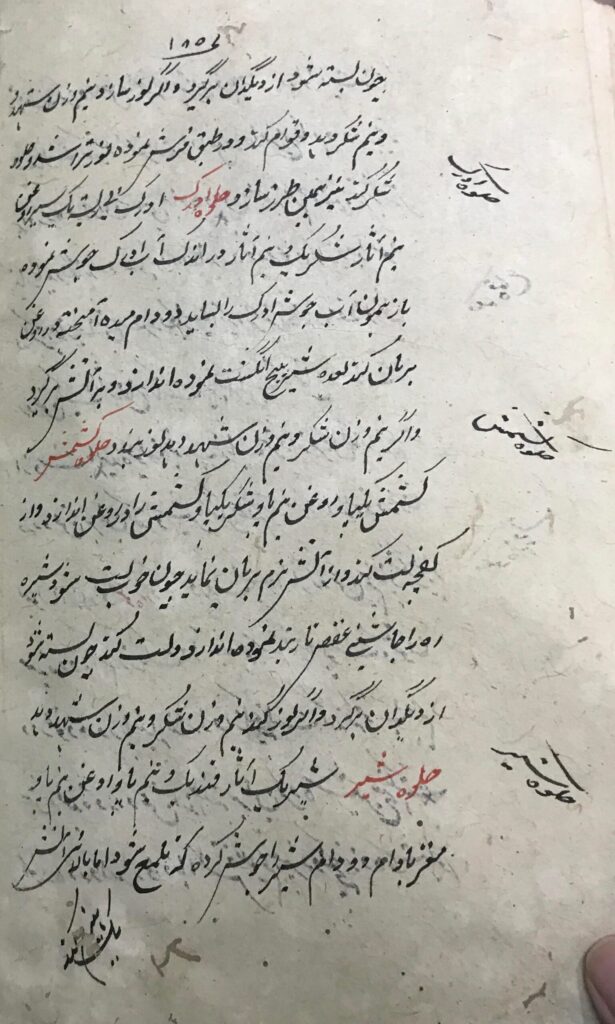

Was it created for an ailing Nawab in the huge Rampur kitchens, or was it an organic amalgamation of multiple cuisines of that period? Culinary exchanges were the norm of the time, and the Rampur cuisine had acquired several dishes and modified their Pathan cuisine under the influence of the Mughal and Awadhi cuisines. Working on a research project centred around culinary memory and lost heritage varieties, I had been translating nineteenth century cookbook manuscripts preserved in the Rampur Raza Library. I turned to these to find the origins of the halwa.

Digging in libraries and kitchens

Known to be culinary connoisseurs, Rampur Nawabs used their elaborate dining tables as a facet of diplomacy. Persian cookbook manuscripts were collected and commissioned by the Nawabs as we collect recipe books—a frame of reference and a guide for culinary transformation. Some of the Persian cookbook manuscripts at the Raza Library are copies of original Mughal or Awadhi cookbooks; a few were commissioned by the Nawabs as reference books of sorts.

One slim volume, Nuskha hai ta’am (Food Recipes), identifies Nawab Kalbe Ali Khan (ruled 1865-1887) as its author. It begins rather unconventionally, with recipes of 11 halwas, most of them variations of the iconic sohan halwa. Adrak halwa doesn’t find a mention in this manual of Rampur cuisine. Another cookbook, Risala dar tarkeeb ta’am (Compilation of Recipes), written under the patronage of Khansaheb Muhammad Shah Khan of Nankar—possibly a nobleman from Rampur tehsil of Nankar—was collected in 1816. This also doesn’t mention the adrak halwa in its repertoire of Mughal and Awadh-inspired dishes. These two volumes are the only ones written under the patronage of Rampur aristocracy.

However, two other volumes—the Risala dar tarkeeb ta’am and Khwaan e Neymat (The Receptacle of Divine Bounty)—contain recipes similar to adrak halwa. It calls for just three ingredients: ginger, sugar and ghee. No milk, cream, spices, and aromatics are prescribed. Published in 1876, Alwaan e Neymat (The Highest Divine Bounty), an Urdu cookbook by Munshi Bulaqi Das Dehlvi, has a similar recipe too.

Interestingly, all the three recipes call for blanching adrak before it is ground to reduce the spicy aftertaste. Adrak halwa was therefore definitely cooked in the nineteenth century in Mughal cuisine. Haft Khwan Shaukat, the oldest surviving cookbook printed in Rampur which ran three editions (1873,1881 and 1883), also doesn’t include the adrak halwa.

I next looked through Shahi Dastarkhwaan—a Rampur cuisine cookbook written by a Rampuri khansama and published in 1957—with several dishes from Rampur cuisine of that time. Latafat Ali Khan Rampuri, the author of Shahi Dastarkhwaan (Royal Dining), describes an elaborate adrak halwa recipe with the list of ingredients corresponding to Muneeza’s heirloom recipe—milk, cream, spices and aromatics along with the basic three ingredients. As in Muneeza’s recipe, no blanching is involved. Rather, the ground ginger is to be boiled in milk. Ali Khan ends with the important line: “Ye halwa Rampur ki tarz par banane ki tarkeeb hai, ummeed hai ki pasand farmaya jayega.” (This halwa is prepared by the special Rampur recipe, I hope you like it.)

At some point in Rampur’s culinary history, the adrak halwa evolved—in the hands of the Rampuri khansamas—into an exquisite sweetmeat with a differentiated procedure and sumptuous ingredients. Today, it is rarely cooked in Rampur households, possibly due to the time and effort involved. Most Rampuris buy adrak halwa from Amanat Bhai’s shop, renowned for its halwa sohan. So that’s where my quest took me next: the kitchen workshop above the famous Amanat Bhai ki Laal Dukan.

Amanat Khan set up shop in the 1930s outside the Rampur fort, and became known for supplying halwa sohan, boondi ladoos and other sweets to Nawab Sayed Raza Ali Khan (ruled 1930-1949), his son Nawab Sayed Murataza Ali Khan as well as for other members of the royal family. The shop is now looked after by Amanat bhai’s grandson, Haris Raza, who inherited the business and recipes from his father.

Haris measured out samnak (wheat germ flour) and semolina, mixed it in milk, and cooked it in a large kadhai; he added ginger paste when the mixture became brownish. This was a completely different recipe for adrak halwa. Samnak is the base for Rampuri halwa sohan, and is never used in adrak halwa. Amanat bhai’s adrak halwa—which is fabulous, with only a slight gingery tang—is a variation of halwa sohan adapted for popular taste.

Most Rampuris buy adrak halwa from Amanat Bhai’s shop, renowned for its halwa sohan. So that’s where my quest took me next: the kitchen workshop above the famous Amanat Bhai ki Laal Dukan.

As the stars of my halwa journey aligned, the district administration of Rampur, in collaboration with the Women’s Welfare Department, decided to organise a halwa festival in October 2021. All the khansamas and women chefs of Rampur—who had started home catering during the covid-19 pandemic—were invited to participate in Zaika-e-Rampur, a halwa-tasting festival. The ingenuity of Rampur khansamas was on full display at the festival. There were several weird and fabulous halwas we tasted that day, including neem halwa, meat halwa, turmeric halwa, and dates halwa.

I had already been working with some khansamas to revive the heirloom dishes of the Rampuri cuisine through our project, ‘Forgotten Foods: Culinary memories and Lost Agricultural Varieties in India’ under the lead of University of Sheffield. The series on Scroll.in was a part of this project. As a social impact effort, we sponsored chef Suroor and Bhura khansama—both local chefs of Rampur—in setting up their stall at Zaika-e-Rampur.

Since my halwa of interest was adrak, I watched Bhura bhai closely as he fashioned a rustic wood chulha, set a large degh on it, and prepared the ginger paste. I was in for a surprise when he fried the ginger paste in ghee for a few minutes, and then cooked it in milk. The frying mellows the aftertaste, he told me. There was no blanching, or boiling in milk. Even the dry fruits for garnish were fried, and added to the halwa.

This was the fourth recipe I had come across, indicative of the circuitous transformations that adrak halwa had undergone through the centuries. Interestingly, the other Rampur khansamas like Mehfooz khansama, who owns a popular restaurant in the city, use the same procedure as Bhura bhai. Some others add jaggery and honey instead of sugar.

I have tasted at least seven variations of adrak halwa through my research, and can say with some authority that the oral history of the Nawab with knee pain cannot be corroborated. Adrak halwa in Rampur—at some point at the beginning of the twentieth century—took on an elaborate form quite different from the Mughal-Awadh style. The people of Rampur made it a part of their winter halwas—one they ate with gusto to combat the cold and heal stiff joints—until it seeped into culinary memories and almost-forgotten manuscripts.

————-

Dr. Tarana Husain Khan is a writer and food historian based in Rampur. Her articles on Rampur cuisine, culture and oral history have appeared in Eaten Magazine, Al Jazeera, Scroll, The Wire, Open Magazine and DailyO. Her book on Rampur cuisine, ‘Rampuri Cuisine: Food History, Memories and Recipes’, will be published by Penguin India in 2022. She is currently working on a Global Challenges Research Fund and Arts and Humanities Research Council funded research project, ‘Forgotten Food: Culinary Memory, Local Heritage and Lost Agricultural Varieties in India’. She also curated the Forgotten Foods series of articles on Scroll for the project and is currently co-editing an anthology ‘Forgotten Foods: a Culinary Journey Through Muslim South Asia’.

source: http://www.thelocavore.in / The Locavore / Home> Culture / by Dr Tarana Hussain Khan / July 12th, 2022

%20course%20-%20Google%20Chrome%2015-03-2023%2017_55_03%20(2)_vb_70.png)