Aurangabad, MAHARASHTRA:

Maulana Abdul Qayyum Nadvi, who has been successfully running his book store ‘Mirza Book world’ in Aurangabad has hit upon another novel plan to quench the thirst of the poor and needy on the roadside.

Every day he buys some cartoons of 300 ml water bottles, refrigerates them overnight and in the morning around 10 am on his way to his book store, when the sun is already hot and shining bright, distributes the water bottles to the road side vendors, beggars and whoever asks for it.

He shared that he began this water distribution activity around 5-6 years back on the occasion of World Water Day. “ At that time, I used to collect empty water bottles from functions, events and gatherings, take them home, sterilise them with hot water, then fill them up, keep them in the fridge and distribute them in the morning to people who were thirsty and could not afford to buy a water bottle”.

“Now, I no longer collect water bottles, I buy them. When my friends saw what I was doing they too joined in and together we pool the money and buy the water bottles. It is much easier,” he explained.

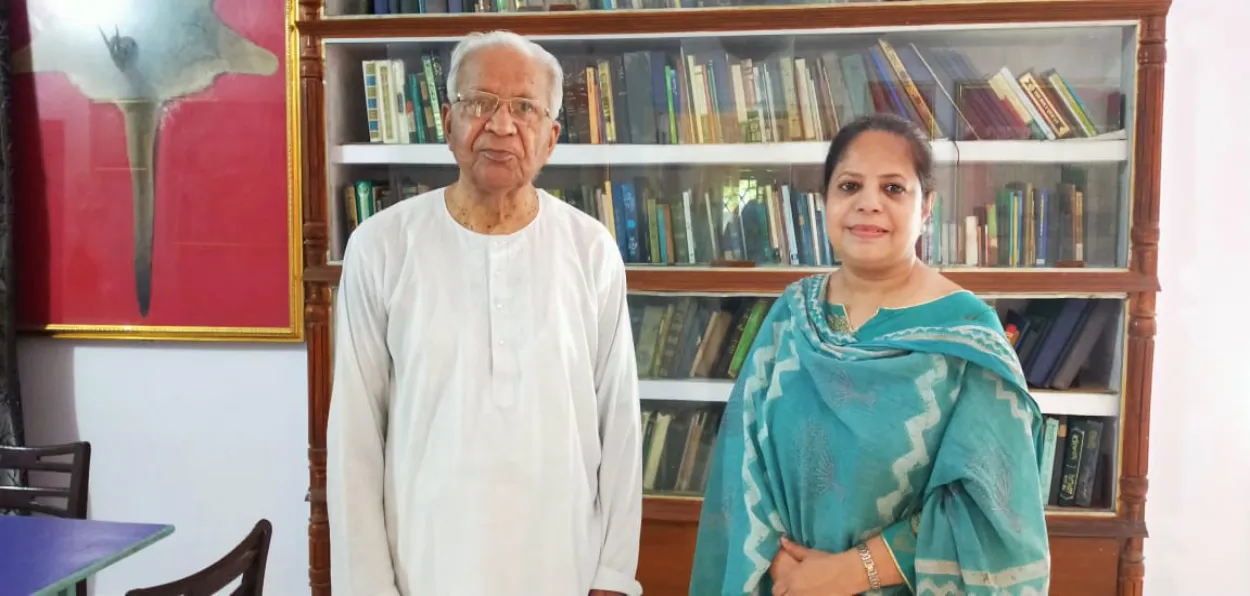

Maulana Abdul Qayyum is not new to social work. He also supports the Mohalla libraries with his daughter Maryam Mirza who is running more than 30 small libraries in the slums of Aurangabad. Many of the books in these mohalla libraries have been donated by the Maulana from his book store.

He runs a foundation called Read and Lead Foundation (RLF) which is mostly about promoting the culture of reading, preserving Urdu language and other social-charity activities with some of his like-minded friends.

“Books have always been my passion”, he said. “ And I chose the career of running a book store so I get to spend my time amidst books. I started the book store in 2002 but before that I used to sell the books on my bicycle cycling around the whole city. It was quite a struggle but it paid off when there were patron demanding books to be supplied in the libraries of schools and colleges,” he added sharing his journey.

Apart from that he has also donated almost 50000 kiddy banks to children in schools in 30 English and Urdu medium schools for the children to save money and buy a book of their choice. His sole aim is to revive the dying culture of reading books.

“ I want children to inculcate the habit of reading a book instead of spending their time playing games on mobile phones. Reading is such a rich hobby, it ignites imagination, helps the children to improve their vocabulary and grasping abilities. But today we see children are no longer interested in reading but after this kiddy bank campaign, I have received positive feedback from the school teachers that students are now reading books in their free time.” he explained with a note of satisfaction in his voice.

His initiative of gifting kiddy banks was picked up by other schools who began gifting the same to their children to get them into the habit of saving money to buy books.

The Maulana then takes time in the afternoon when the sun is at its peak to ride around the vicinity with his bags of water bottles and distribute the cold water to the thirsty people irrespective of their caste, religion, gender, he sees on the roadside. His daughter ordered customised bags with the caption: ‘ Choti si neiki, Pyase ku pani’ which can hold at least 50 bottles.

“ Many passersby give coins to these beggars but when I give them a water bottle, they are happy and utter blessings, their happiness clearly visible on their faces. It gives me satisfaction when I see them drinking the cold water”, he shared beaming with happiness.

He also explains that he is not after recognition or awards. He does these activities because he wants his 5 children to look up to him and learn good values. Good morals and principles to lead a righteous life as per Islamic Values is the legacy I want to leave behind.

But awards have also come his way when he has been covered by the media for his earlier work of mohalla libraries, distribution of kiddy banks, promoting Urdu, water distribution program.

Nadvi’s efforts for preserving Urdu through the foundation have not gone unnoticed. He received the ‘Shaan- e- Aurangabad’ award in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in 2023 by the Aurangabad Jeddah Association. The Maharashtra Urdu Academy and the Telangana Urdu Academy have both awarded him. Many other organisations have felicitated him for his efforts to promote Urdu and reading culture.

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home> Positive Story / by Nikhat Fatima / by Muslim Mirror / April 01st, 2024

:focal(5160x3330:5161x3331)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/d1/0cd129c2-7c42-455e-8e45-6ae7b7da7fce/dec2019_d01_prologue.jpg)