Heritage

Karnataka owes much of its position as one of the top-ranking horticultural states in the country to the initiatives taken by Tipu Sultan, who sent missions abroad to collect seeds of flowering plants, vegetables and fruits including the famed Ganjam fig and the Devanahalli pomelo, writes S Tahsin Ahmed.

On December 10, 1985, when I accompanied the CBI team as the official witness in a raid conducted at Mysore during which a sword belonging to Tipu Sultan was seized, I visualised Tipu as a brave and valiant king who died fighting the British invaders. Later, I realised that Tipu Sultan was a much celebrated ruler in the history of South India not just for his military exploits, but also for his contributions in the fields of sericulture, rocketry, animal husbandary, social reforms, handicrafts, trade and commerce, etc. There is another major achievement of Tipu Sultan that has not been highlighted enough: his contribution to the field of horticulture.

In fact, Karnataka owes much of its position as one of the top ranking horticultural states in the country to the various initiatives taken by Tipu Sultan in his 18-year rule (1782-1799). Today, horticultural crops are raised on 18.99 lakh hectares of land in Karnataka, accounting for about 15.07 per cent of the total cultivable area.

What do historical records reveal?

In 1799, immediately after the defeat of Tipu Sultan, the British asked Francis Buchanan to survey South India which resulted in the publication of the historical work, ‘A journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar (1807)’. This book gives an interesting account of horticultural fields which were called tota, as existing during Tipu’s regime. “In the ashta gramas, there are four kinds of tota or cultivated garden lands, tarkari tota or kitchen gardens; tayngana tota (read tengina) or coconut gardens; but many other kinds of fruit-trees are planted in them; yele tota or betel-leaf gardens; huvina tota or flower gardens.” Buchanan also lists 48 vegetables grown in the areas ruled by Tipu Sultan.

Francis Buchanan took notes at lectures at the Botanical Garden, Edinburg in 1780 (before he came to Mysore) which got misplaced. Through another traveller, it accidentally reached Srirangapatna and came to the possession of Tipu Sultan. Tipu got this manuscript bound in tooled leather and added it to his big library, a reflection of his interest in botany and passion for horticulture. His library included many books on management of fruit trees.

Tipu kept up a sustained campaign against feudal chiefs called palegars who usurped land belonging to farmers. Land seized from palegars was handed over to farmers, tenants and bonded labourers. Tipu, it seems, was one of the earliest champions of the land reforms movement. Farmers were encouraged to expand the area of horticultural cultivation. Waste lands were exempted from rent in the first year of cultivation which was followed by tax concessions in the succeeding years. Incidentally, area expansion is one of the major schemes of the National Horticultural Mission today.

Tipu had a huge army and military police, to whom he gave cultivable land in addition to regular pay. Low-level workers like nirgunties were also allotted land to boost cultivation. He is the only king in the history of Karnataka who did not grant a single jahgir. These anti-feudal reforms had a far-reaching impact on the growth of agriculture and horticulture.

Missions abroad

An 80-member mission headed by Mohammed Darwesh Khan was sent by Tipu to France. The mission reached Paris on July 16, 1788, and met the French emperor and handed over a memorandum given by Tipu.

Among other things, the memorandum demanded seeds of flowering plants, vegetables, European fruit plants and trees. The mission was successful in procuring spice plants and camphor seedlings from Molucca.

A huge trade mission was sent by Tipu Sultan to Turkey which met Sultan Hameed in Constantinopole on November 5, 1787. It carried large quantities of black pepper, cardamom, sandal wood etc and succeeded in identifying an overseas market for this produce.

The mission brought back seeds of many flowers, vegetables and fruits. The famous Ganjam variety of fig was brought from Turkey.

Tipu Sultan wrote letters to the darogha at Muscat and instructed him to buy saffron seeds and date palms. The darogha was also asked to obtain silk worms from Qishm island and send them to Srirangapatna alongwith a few men knowledgeable about sericulture.

Farmers were encouraged to cultivate mulberry in their lands. In several diplomatic and trade missions sent by Tipu Sultan to countries like Muscat, Oman, Jordan, Iraq, Iran and Penang, export and import of horticultural produce was a major component.

Role of Thigalars

Tipu noticed that a class of people called Thigalars near Salem had expertise in cultivation of vegetables.

He encouraged them to migrate to Bangalore, Hoskote, Kolar, Devanahalli and Sira, which boosted the cultivation of vegetables in Karnataka. Other measures taken were to exempt farmers growing vegetable crops and cash crops like cashew, cardamom and cinnamon from payment of land revenue. The famous Devanahalli pomelo was also introduced by Tipu.

It was made mandatory for the village patels to plant avenue trees on either sides of the roads throughout his kingdom. But the interesting aspect here is that Tipu ordered planting of mango and tamarind trees among other trees which reveals that preference was given to useful trees over ornamental or just shade-giving trees.

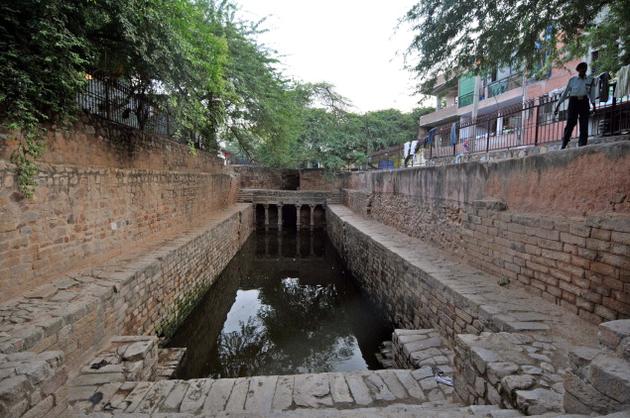

Establishment of gardens

One wonders how Hyder Ali, father of Tipu Sultan, who was in the thick of military campaigns throughout his reign, found time to establish gardens. Hyder who had a taste for gardens (‘Char-bagh’ style), planned Lalbagh on 40 acres of land at Bangalore along the lines of Khan Bagh at Sira, established during the time of Dilawar Khan, the representative of the Moghul emperor in the South.

He imported plants form Delhi, Multan, Lahore and Arcot, apart from laying out a garden at Malvalli and another fruit garden at Srirangapatna, also called Lalbagh.

Tipu expanded Bangalore’s Lalbagh by acquiring more land. The garden was earlier known as cypress garden because the roads from the entrance to the garden and inside the garden were lined with cypress trees.

This is evident from a painting of this garden drawn on the spot by R H Colebrooke and published in 1793 at London. Another painting of the Lalbagh by James Hunter published in 1805 and showing many cypress trees is captioned ‘East view of Bangalore with the Cypress garden.’

Equally magnificent was the Lalbagh at Srirangapatna. The Gardens around the Gumbaz where both Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan are buried were full of fruit trees, flowers and vegetables of every description. This Lalbagh is also believed to have served as a nursery for the kingdom. Fruits like apples, pears, guava and plantains were successfully grown here. Imagine apple trees in a place like Srirangapatna and that too in the 18th century! Also grown were betel nuts, coconuts, sandalwood, sugarcane, indigo, cotton, mulberry, cereals and pulses.

In the Third Mysore War (1792), the cypresses of Lalbagh at Srirangapatna were axed to provide firewood for British troops. After the war, Tipu restored much of the glory. But in the final war of 1799, British troops breached the fort wall and devastated Lalbagh. Nothing remains of this garden except a painting of the entrance to Lalbagh at Srirangapatna by James Hunter (1805).

The fruit orchard at Malavalli also no longer exists. Buchanan who visited this garden after Tipu’s death noticed 2,400 trees with mangoes and oranges in abundance. The garden surrounding the Daria Daulat Bagh at Srirangapatna was more of an ornamental garden, but very well maintained.

Tipu Sultan’s love for horticulture was so great that he linked this with dispensation of justice. For petty offences, convicts had to plant fast growing plants and for major offences, they had to plant trees like jamun, mango and coconut. In 1788, Tipu Sultan issued a circular to all amildars and in 1792 he passed a regulation that the fines of the farmers shall be commuted if the offender plants two trees, waters them and nurtures them till they reach a certain prescribed height.

Can we think of a better environmentalist among kings gone by, long before environment and climate change became fashionable slogans?

(The author is Additional Director of Horticulture (Administration), Lalbagh, Bangalore.)

source: http://www.deccanherald.com / Deccan Herald / Home> Supplements> Spectrum / by S. Tahsin Ahmed / July 04th, 2011