Chennai, TAMIL NADU / Madison (WI) , U.S. A. :

In ‘The Lucky Ones’, Zara Chowdhary, who survived the 2002 Gujarat riots, recasts her memories into a bold assertion of identity beyond trauma.

the 2002 riots. | Photo Credit: JANAK PATEL

Most of us suck at telling the truth. We would rather dress up facts into stories, tie them up with a neat disclaimer: this is a work of fiction. A memoirist is a person so caught in the nuclear fallout of overpowering, unspeakable facts that she must set aside the pretense of fiction and simply assert, this happened. Saying “I lived through this” becomes a way to unpin the self from the yoke of a toxic and restrictive past. Calling things by their name frees the soul.

But writing a memoir is a tricky terrain to navigate. Why should the world be concerned with what happened to someone? How is anyone to know if the person is telling the truth? They may simply be begging for cheap pity by recounting some traumatic truth. Even when a memoir is truthful, trauma tends to constitute a totalising identity, says the literary critic Parul Sehgal of The New Yorker, by making a singular event the whole story, the definitive story. From this point of view, the very claim of truth a trauma narrative makes is suspect.

Most of us suck at telling the truth. We would rather dress up facts into stories, tie them up with a neat disclaimer: this is a work of fiction. A memoirist is a person so caught in the nuclear fallout of overpowering, unspeakable facts that she must set aside the pretense of fiction and simply assert, this happened. Saying “I lived through this” becomes a way to unpin the self from the yoke of a toxic and restrictive past. Calling things by their name frees the soul.

But writing a memoir is a tricky terrain to navigate. Why should the world be concerned with what happened to someone? How is anyone to know if the person is telling the truth? They may simply be begging for cheap pity by recounting some traumatic truth. Even when a memoir is truthful, trauma tends to constitute a totalising identity, says the literary critic Parul Sehgal of The New Yorker, by making a singular event the whole story, the definitive story. From this point of view, the very claim of truth a trauma narrative makes is suspect.

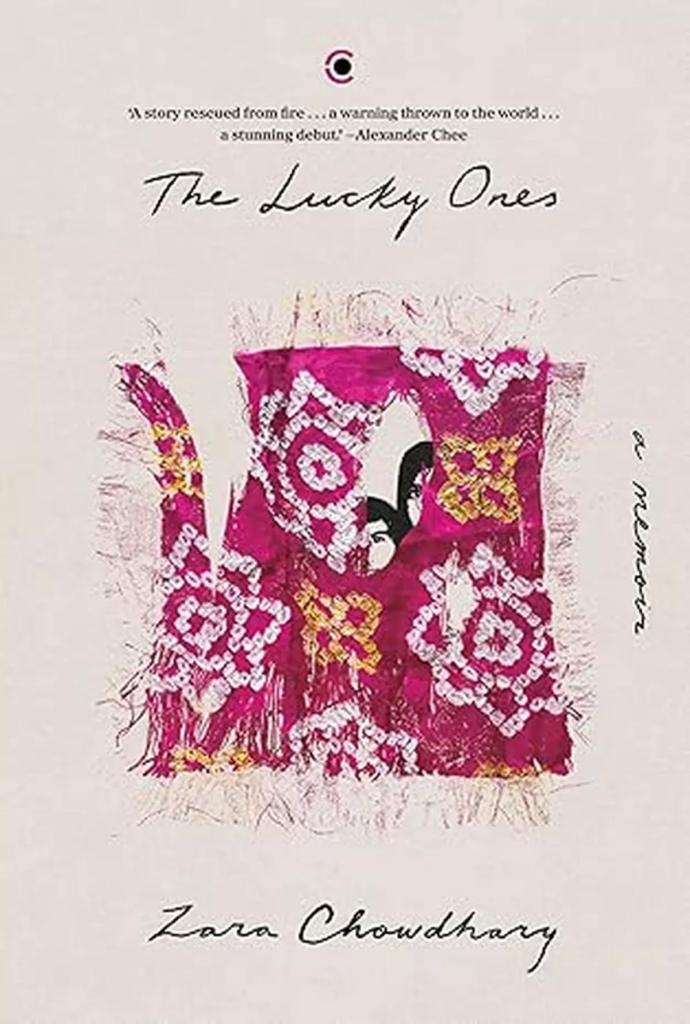

The Lucky Ones: A Memoir / By Zara Chowdhary

Context / Pages: 342 / Price: Rs.699

Zara Chowdhary’s memoir of coming of age in 2002 Ahmedabad incinerates all such reservations in the first few pages. The title sets the tone by making the point that it was her family’s great fortune to have survived “those days” physically unscathed. The narrative begins with the terrible feeling of being a marked people, of living holed up in a flat “waiting for the mob to find us” in a city where laws and rules have ceased to exist, closeted with a dysfunctional family. Around them, headlines spew hate, rumours fly, and black smoke fills up the sky and the television screen. The narrative moves inward and holds to light multiple threads of identity that bind her people in one family, her family to the city and its society, and the citizens to a nation. This brings a deep awareness of how violence within the family or outside unravels the most essential, joyful aspects of any identity whether one is a victim or the perpetrator.

The facts around which the narrative unfolds have been so extensively documented, written about, probed by courts, parliaments, tribunals, and fact-finding missions that they constitute the nation’s subterranean truth. The author intersperses reportage with lived experience, weaves Gujarat’s history with her own family’s past, to provide context to her endeavour of processing the anger at what she experienced and helplessness with her father’s denial and minimising of it, which was the only way he knew to cope.

Curfewed terror

Early on, Zara came to the realisation that no strongman could save them.

“…The madness in our home, like in the rest of this country lay in our search for a strongman. In our home no man is strong enough. Dada is haunted by how he failed. Papa withers under the burden of his own mistakes. The women become dictators….”

In the city that is the only home she knows, Zara is preparing for her board exams in the cramped and dark family home while “history is happening on the streets”. For the next three months as the city burns, the eighth-floor family home, C-8 Jasmine, in a 40-year-old building in a Muslim area, will be their prison. Zara approaches the task of reliving those days by opening the door on the othering and suffocation experienced within the four walls of her own home. Her Gujarati-speaking Dadi considers her south Indian mother an outsider. Proud of her anglicised antecedents, her college-educated Dadi—who came of age in the pre-Independence years when her elite family were people of consequence in the city—holds sway over the household. She grew up playing badminton and dancing at the club and even now wears chiffons and pearls.

Disgruntled with the gradual lowering of their status and circumstances, Dadi kept her Punjabi Muslim “peasant” husband on a tight leash until he passed away and hates her dusky south Indian daughter-in-law. Both her granddaughters are terrified of her. Zara’s father, a pampered, educated-in-the-US son, is now a mid-level employee in the electricity board who faces daily humiliation in the office because he is a Muslim. Unable to either assert himself or to take the microaggressions in his stride, he copes by drinking heavily and bullying his wife, often encouraged in this by his mother. In view of the deteriorating situation, her father’s younger sister phupo, an imperious college professor and a divorcee who lives on “the other (Hindu) side of the city”, also moves into their flat with her daughter, who is a superior and disdainful apa to Zara and Misba.

Struggling to make sense of her family is a part of her struggle to process the curfewed terror of those three months. Why was her father so easily bullied by the world? Why was he so willing to undermine his wife all the time? Why did her intelligent, honey-eyed mother submit so willingly? Zara’s prose carries the weight of every question and reveals that belonging and unbelonging are not givens but manufactured prejudices “that offer security but in return [for] your unquestioning loyalty”. Whether in families or in nations.

Everyone in her family has a past made of things that make them less hateful. Dadi—who loves to spread disinformation about her daughter-in-law, which Zara’s father is only too ready to believe—is at her best when dancing the garba. The only time she is proud of her twinkle-toed granddaughters is when they are doing the bhangra or the garba. Just as flying kites during Uttarayan is her father’s secret superpower.

Denial, diminishment, erasure

To understand why her family is the way they are, Zara gently probes the past of each family member—which is also her past. Thus, she can look at what they do without losing the gifts that her diverse heritage brings. Examining the fault lines within her own house enables her to ask the question of home and belongingness at multiple levels. This question that simmers inside chants and slogans hurled from across the dry riverbed also lurks in the animosities in her own house. The denial, diminishment, erasure practised within the family as on the streets is a game of numbers and power. The excavation of family politics lends great moral clarity to Zara’s examination of other alienations inflicted upon them, and gratitude for the things that sustain them. What sustains the girls is their mother’s love, the hope inspired by the kindnesses of their Hindu friends, and above all their ability to dance to Bollywood numbers even in terrible times, because what is the alternative?

When the curfew is partially let up, it is time for Zara to write the now meaningless examinations in centres located (deliberately) in Hindu localities. Some even inside temples. Her rattled family steps out for the first time, and more than the exams her focus is on trying to look like a non-Muslim. She thanks her mother’s wisdom in giving her a neutral sounding name. Once the exams end, her rich Hindu classmates, who never once called up to check on her all through the terrible months of March and April, blithely propose an outing. Zara declines, citing the situation. Her friend counters by scoffing: “What rubbish yaar, there’s been no curfew for months.”

This heart-wrenching moment stays with the reader. In this moment, the young Zara registers the difference between herself and “them”—whose cushy lives never stopped in the tracks because of unremitting violence. Who never experienced the terror that reduced her family, her building, her Muslim neighbourhood to a bundle of nerves.

“Our loss doesn’t exist. Our pain isn’t real, it never happened. Their malls still brim, their restaurants fill with chatter… while we live hunkered in our own homes…. We live in two different Ahmedabads, two different Gujarats, two different Indias.”

All these experiences sharpen her ability “to distinguish between the oppressed and the oppressor” and bring in her “a refusal to live life as either”. This clarity enables her to wrest back the agency denied to her by her city. Her need to be not defined by trauma shines throughout the book. She has taken her lessons but also come to the realisation that her faith and belongingness as an Indian Muslim are not what others get to define. Her unique identity comes to her through the Punjabi, Gujarati, south Indian Islamic strands of her family, and no one else’s definitions can wrest this away from her. A text of such radical empathy can emerge only when the author has unflinchingly held the sharp blade of memory, of times unspeakable and times happy, in her bare hands and stayed with them until out of the silence emerges her truth, her belongingness story, her way out of the dungeon of erasure.

Varsha Tiwary is a Delhi-based writer and translator. She recently published 1990, Aramganj, a translation of the bestselling Hindi novel Rambhakt Rangbaz.

source: http://www.frontline.thehindu.com / Frontline / Home> Books> Book Review / by Varsha Tiwary / January 14th, 2025