INDIA :

Events singling out the Muslim community have led to young women asserting their identity through modest fashion—the hijab, abaya and burkha—driving up sales and provoking new fashion trends and questions about Muslim womanhood in India.

On a warm February afternoon, fresh roses and orchids adorn the entrance of Mushkiya, a newly opened Mumbai store which retails hijabs and abayas. Inside, there is a sparkling chandelier and a changing room with remote-controlled pink curtains—a stark contrast to the musty tailor shops and chai stalls on the noisy and narrow road in Santacruz. Groups of women in burkhas, mostly black, come in to look at the neat display of more than 500 garments. There is excited chatter about what’s pretty and pocket-friendly.

This is Mushkiya’s fourth store in the city. Later this month, they are set to open the fifth, in south Mumbai. “Then we will move to tier 2 cities in Maharashtra, like Nashik, Jalgaon and Aurangabad,” says Arif Panjwani. He owns the franchisee venture, West Trading Company, which brought the Delhi-based brand to Mumbai. Mushkiya’s founder, Zeeshan Arfeen, says he started as an online retailer selling hijabs and abayas in 2016, and quickly went on to establish nine stores in Delhi and four in Mumbai.

Hijabs, abayas and burkhas have never been as ubiquitous in the national consciousness as they have been in the last three months, with images of Muslim women in Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh splashed across various media. Mushkiya, in fact, has a Shaheen Bagh connection. Its first store in the heart of Shaheen Bagh has remained shut for 14 weeks now, ever since the area transformed into the epicentre of the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) protests in the Capital, inspiring similar protests in Mumbai, Bengaluru and Kolkata. From Shaheen Bagh to the viral videos of young hijab-clad students of Jamia Millia Islamia standing up to the police, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that the hijab has emerged as a symbol of dissent. It’s a far cry from the muscle-flexing, bandana-wearing Rosie the Riveter, an American pop culture icon created during World War II to implore women to take up jobs and help make arms and ammunition for the war. The hijab-clad woman is a tour de force who creates spaces to fight for equal rights. And most importantly, she is real.

THE BURKHA BUSINESS

As a symbol of religious personal identity, the hijab and burkha have gone through highs and lows. However, in the past few years, young Muslim women have embraced and adapted the garments in innovative ways, ensuring the hijab’s entry into the world of runway and Instagram fashion.

In February 2019, fashion designer Muneeba Nadeem, 23, then a third-year student at the International Institute of Fashion Design, Kanpur, debuted at the Lakmé Fashion Week’s INIFD Launchpad, with a collection that focused on hijabs for working women. It was the first time the hijab appeared on the runway of a “mainstream” fashion event in India. Kanpur-based Nadeem says over the phone that she wanted to drive home a point—modest clothing can translate into power dressing too and is deserving of greater recognition.

Modest fashion is an umbrella term that comprises full-length garments, from long-sleeved blouses and floor-sweeping dresses to outerwear, and refers to modes of dressing that conceal the wearer’s body shape and limit skin exposure. Nadeem wants to establish her business in Kanpur before venturing into a bigger city, though she does sell on Instagram. The budding designer owes her success to her father, who encouraged her to establish her business before thinking of marriage. Now, she plans to work on her spring/summer 2021 collection to participate in the Lotus India Fashion Week and the Dubai Fashion Week.

In India, despite a slowing economy, the modest fashion industry is witnessing a revolution of sorts. Instagram is teeming with independent apparel brands and hijab-centric labels, such as Little Black Hijab (@shoplbh; 81,700 followers), Hazel Hijabs (@hazelhijabs; 18,000 followers) and That Adorbs Hijab (@that.adorbs.hijab; 17,400 followers).

When Little Black Hijab (LBH) launched, co-owners Farheen Naqi and Fatima Mohammed maintained higher price points, around ₹750 for everyday options, because there was no competition, but they had to reduce rates to around ₹499, as new brands proliferated. “Now, at least 10 new Instagram shops crop up every day,” says Naqi. LBH opened shop on Instagram in 2016 because Naqi couldn’t find quality hijabs in India.

Brands like Delhi’s Mushkiya, Mumbai’s LBH, Chennai’s Islamic Shop and London-based Islamic Design House (IDH)—all opened for business in India around the same time, in 2015-16. Their target audience includes women across a wide spectrum of preferences and age groups—from die-hard Kartik Aaryan fans to those who spend weekends watching reruns of Fleabag on Amazon Prime.

According to Salaam Gateway, a Dubai-based media platform that tracks the global Islamic economy, “India’s 170 million Muslims spent an estimated $11 billion (around ₹80,860 crore) on clothing in 2015 and this is expected to grow at a CAGR of 13% to reach $20 billion by 2020.” It has identified factors such as population increase, urbanization, and a younger, more brand-conscious demographic, for the growth of modest fashion in India. Style inspiration powered by social media platforms has also contributed to this. Junayd Miah, co-founder of IDH, is most optimistic about retail opportunities in tier 2 cities. “Globally, the modest fashion industry is set to expand,” claims Miah over the phone from London. “In India, it is ready to explode now.”

THE GLOBAL RISE OF MODEST FASHION

“When a community is put in the spotlight and its people feel marginalized, they turn inwards to explore their identity,” Miah says. In the 9/11 aftermath, which saw ordinary Muslims the world over targeted for their identity, the younger generation, across Europe and the US, began to grapple with questions of religious identity and ask themselves what it meant to be Muslim. But this was also an experimental, fashion-forward generation that wanted to explore new trends and styles while remaining within the tenets of modest dressing laid down by their faith.

Modest fashion is conservative, but it doesn’t have to be boring. The diversity available in the market is astounding—from asymmetrical hemlines and animal prints to sequinned tops and Billie Eilish-approved electric green. There are denim abayas in different washes and ones with sportswear-inspired accents like stripes and pockets. Burkhas are no longer shapeless and baggy: A-line cuts are common, rhinestone detailing has become popular, and colourful headscarves accessorize the garment. Our favourite in the course of researching this feature, is a Mondrian-inspired pattern by Mushkiya.

Modest fashion also encompasses other faiths, such as orthodox Jews and Christians. A 2019 article in The New York Times, headlined “The Co-opting Of Modest Fashion”, expanded its definition, pointing to “the cultural shifts that followed the #MeToo movement, as many women rejected the male gaze”. It put the spotlight on personal choice independent of religious beliefs and highlighted the fact that modest fashion has transformed into an alternative mode of dressing. Case in point, the hooded, full-sleeved, A-line silk lamé Ralph Lauren gown studded with 168,000 Swarovski crystals worn by American singer and rapper Janelle Monáe on the Oscars red carpet this year. Last month, Deepika Padukone attended the Mirchi Awards in Mumbai in a black bodysuit by Balmain with black sky-high stilettos and black blazer. The hood had soft drapes like a hijab scarf. What was it if not a nod to “an alternate mode of dressing”?

MY HIJAB, MY CHOICE

The question of choice was brought into the limelight most recently during a social media altercation between Khatija Rahman, singer and daughter of music director A.R. Rahman, and Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasreen. On 11 February, the latter tweeted that she feels “suffocated” by Khatija’s burkha. Khatija took to Instagram to assert her choice, saying, “I’m proud and empowered for what I stand for.” Rahman’s argument was that a woman is free to wear what she wants.

Hijabs and burkhas tend to evoke extreme reactions: While the Taliban regime in Afghanistan would whip women without burkha, on the other end of the spectrum, Denmark last year banned this garment in certain public spaces.

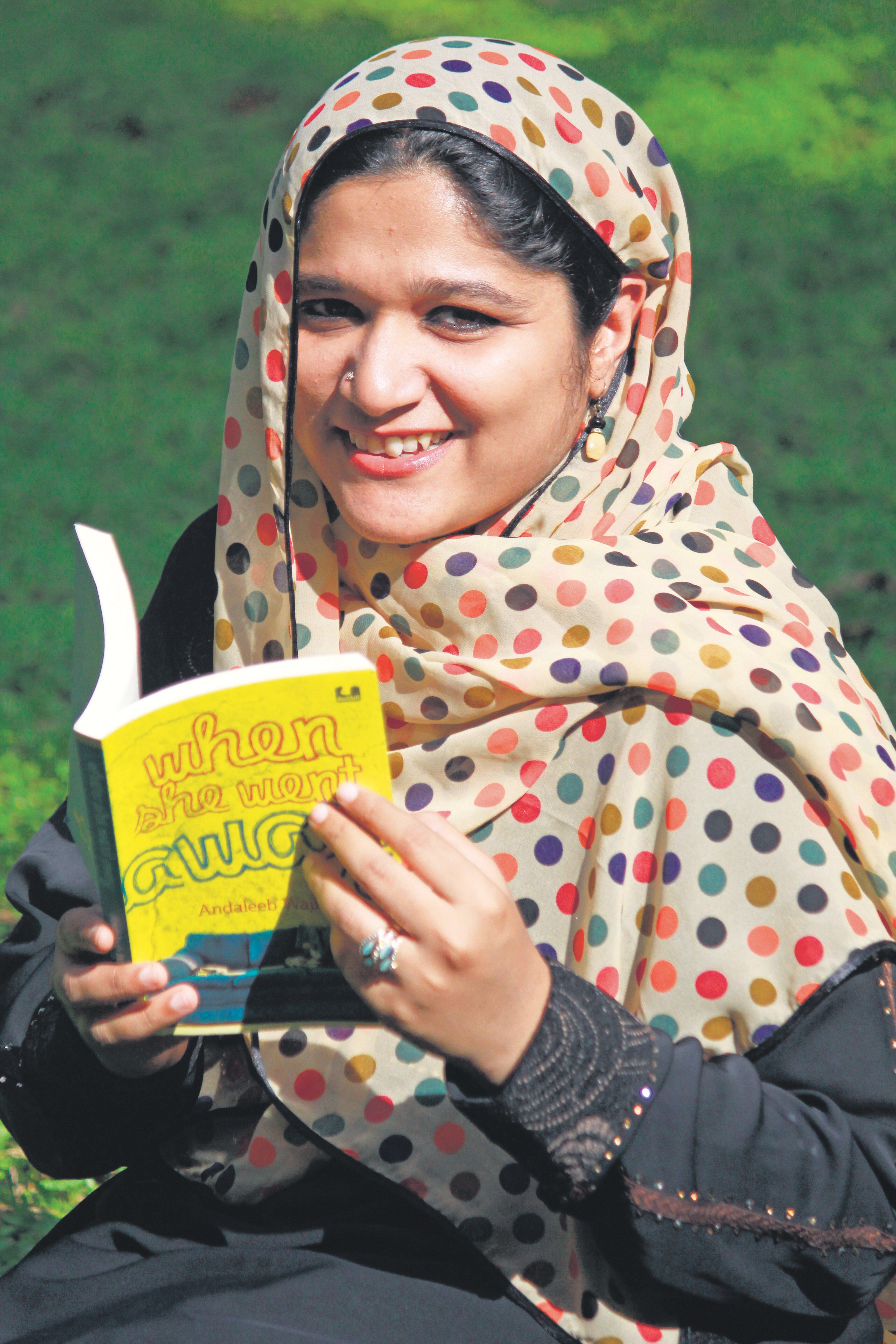

“The stereotype of the burkha being oppressive doesn’t exist for the one wearing it. It is perceived as oppressive by the ‘other’,” says Bengaluru-based novelist Andaleeb Wajid. “When I was younger and attended book launches in five-star hotels, I didn’t want to wear a burkha, because of this notion of ‘what will people think’,” says Wajid, 42, who started wearing it in her teens because most women in her family did. Even now, when Wajid attends literary events, people start a conversation with her in Hindi rather than English—though she is the author of over 24 English language books. “Just because I am wearing a burkha, it doesn’t mean I only speak Urdu,” says Wajid. She likes to pair them in muted colours with printed or coloured hijabs for a “pop of colour”. “I feel I look really nice.”

Clearly, more and more women are experimenting with modest fashion in India. It is no longer a binary: a girl in a black burkha or one without. A spectrum has come into play, and style influencers are adding to it in creative ways.

In Mumbai, Nabeeha Fakih, a 25-year-old dentist, documents her hijab-centric outfits on Instagram for her 53,500 followers. For her wedding, she styled the hijab in a manner that partly showed her hair. She got trolled but she takes it in her stride. “I just feel that what is right for me may not be right for you,” she says.

She says a girl should understand the purpose of wearing a hijab—which is to behave in a modest manner—based on what works for her. “I feel when you wear the hijab, focus on your intentions and understand why you are wearing it,” she explains. On YouTube, she posts hijab tutorials for her 21,000-plus followers. “I can’t style my hair, so I style my hijabs,” she says. She receives messages from girls who took to the hijab after watching the videos.

Twenty-one-year-old Anah Shaikh (featured on the cover), a hijabi influencer (@_hadha.ana_) with a following of 65,800 on Instagram and 63,000 on TikTok, started wearing the hijab in her early teens. When she turned 19, she started her Instagram page to document hijab-centric personal style outfits. Now, she is one of the leading names in the hijab influencer universe in India and has collaborated with global brands such as Daniel Wellington, Beep Global and Sugar Bear Hair.

“I wanted to attract Muslims and especially non-Muslims via Instagram,” says 20-year-old style influencer Sana Sayyad (@sanasayyadx). She has been posting personal style updates on the platform since 2018 and within a year, there were paid collaborations with Indian modest fashion and beauty brands like Modest Essentials, Thread For Your Head and Iba Cosmetics, a Peta-certified halal make-up label.

IDH has tapped into the burgeoning community of fashion enthusiasts in Kozhikode with events like Modesty Meet-ups and Hijab Styling workshops at its store. Its Instagram page @idh_india has highlights from these events. For Modesty Meet-ups, the brand involves hijab-wearing women from creative professions like photography who share their journey with modest fashion as they explore why they dress the way they do.

LBH offers quick tutorial videos on Instagram for styling the hijab, with hijabi influencers that generate anywhere from 10,000-100,000 views. “It’s almost like a small digital magazine to offer inspiration on how to wear it. It is not like we are pushing girls to buy. It’s more about fun styling,” says Naqi. It involves exploring drapes and experimenting with accessories such as baseball caps, winter beanies, sunglasses and earrings. All the videos are in sync with global hijab trends. They even offer content categories like back-to-college and 9-5. They have yet to receive sourcing requests from a prominent brand “but in the Muslim world we are quite mainstream”, says Naqi.

BREAKING THE SILOS

In recent years, more and more style-conscious Indian Muslim women can be seen sporting the Khaleeji hijab, a style of wearing a headscarf over a large bun that gives the head and neck an elegant silhouette. Originating in Kuwait, the Khaleeji is among the most popular hijab styles across the world today, with hundreds of YouTube tutorials guiding women on how to drape it. Wearing the hijab in a no-fuss manner with fewer pins and drapes is another favoured style.

In LBH’s office, I come across an assortment of hijab accessories: Stretchable caps, cotton blend and lace, which are worn underneath the hijab to tuck in hair and keep the scarf in place, hair volumizers and hijab pins, including no-snag and magnet versions (the latter will even secure a heavy Kanjeevaram sari). Essentially, they are a pair of strong magnets decorated with studs or pearls which are placed on either side of a fabric to keep it in place and double up as a brooch with zero damage. “Magnetic pins are so effective that you can wear the hijab, ride a bike and it will not move an inch,” says Naqi.

At a pop-up exhibition last year, non-Muslim women were quick to buy these too. “Thirty per cent of our buyers are non-Muslims,” says Panjwani of Mushkiya. Two aspects of these products appeal to women who are not their target customers: attractive pricing and variety. LBH, for instance, retails office-appropriate three-piece and two-piece coordinated sets and long jackets. It also offers bridal options with Lucknawi hand embroidery. Georgette-blend long jackets with floral prints can be found at Mushkiya’s online and offline stores too, while IDH sells jumpsuits, long button-down dresses and modest swimsuits with a head cover.

Mushkiya’s store in Santacruz is labelled as “premium”, but the clothes are surprisingly affordable. The hijabs are priced between ₹120-700, while abayas cost ₹990-12,000. The hub for abayas, burkhas and hijabs in Mumbai, however, is Mohammed Ali Road, where they are sold on the street as well as in retail stores. Hijabs here can be bought for ₹120-250. LBH’s quasi-formal coordinated-sets with matching trousers and tops range from ₹1,000-2,000, lower than Amazon’s prices for similar garments. IDH offers spiffy mid-length buttoned dresses with asymmetrical hemlines priced at ₹1,500-2,600. These are marked down during sales—the attractive pricing brings in non-Muslim customers too.

BOLLYWOOD AND THE BURKHA

In recent Bollywood movies such as Secret Superstar and Lipstick Under My Burkha, women are shown to have a complex relationship with the hijab and burkha. While the burkha is often shown as a convenient way to maintain freedom—a sort of urban camouflage—it can also become a symbol of all that is oppressive. In Secret Superstar, the protagonist is forbidden by her father to sing publicly; towards the end of the movie, she removes her face cover. In Lipstick Under My Burkha, one of the two Muslim protagonists uses the burkha to shoplift.

Most girls in hijab that Lounge spoke to believe that the only “real” representation in Bollywood of a young Muslim girl who dresses modestly and wears the hijab is portrayed by Alia Bhatt’s character, Safeena, in Gully Boy. The movie was styled by Poornamrita Singh, who researched for several months to style the feisty Safeena. Her team visited multiple colleges in Mumbai and took photographs of girls in hijabs, with their consent. Singh learnt about the various drapes and accessories to develop a mood board. Then she sourced basic jeans and T-shirts from brands like Uniqlo, kurtis and hijabs from street shops and created Safeena’s look.

“I wanted to ensure that the hijab didn’t stand out,” says the stylist. “… That it was as regular as wearing a pair of jeans.”

source: http://www.livemint.com / Live Mint / Home> Explore / by Jahnabee Borah / March 08th, 2020