Srinagar, JAMMU & KASHMIR :

“Afsoos duniya, kaen’si ma loug samsaar seethi, Patau lakaan wuchte kum kum mazaar weati.”

“Alas, this world was never a companion to anyone; look at the people, the graveyards they have finally landed in.”

These lines from the poetry of Sufi poet, Rajab Hamid, are immortalised in Kashmir’s memory through the famous song Afsoos Dunya, sung in the powerful voice of the famous Ghulam Hassan Sofi. The rendition was recorded under the label, Music Tape Industry (MTI), back in the 1990s when audio cassettes were in vogue.

A small music label, the MTI has produced several songs that have made a mark in Kashmir. Allah Ti Hoo Hoo and Vaadh Sariyo by Gulzar Ahmad Ganie, Madan Waras Bah Pyaras by Abdul Rashid Hafiz, were among the songs that became an instant hit in the Valley.

As folk and sufi music became accessible–Kashmiris no longer needed to wait for these songs to be played on the radio–the demand for these records increased and MTI’s reach spread to several households across the Valley, that was simultaneously in the throes of a deadly conflict.

By the 2000s, the MTI diversified to produce music videos, updating their music styles and changing their formats to cater to the public’s taste and demands. Decades later, its journey has forayed into the online media but MTI doesn’t fail to ring in nostalgia of a bygone Kashmir.

Immortalising Kashmiri music

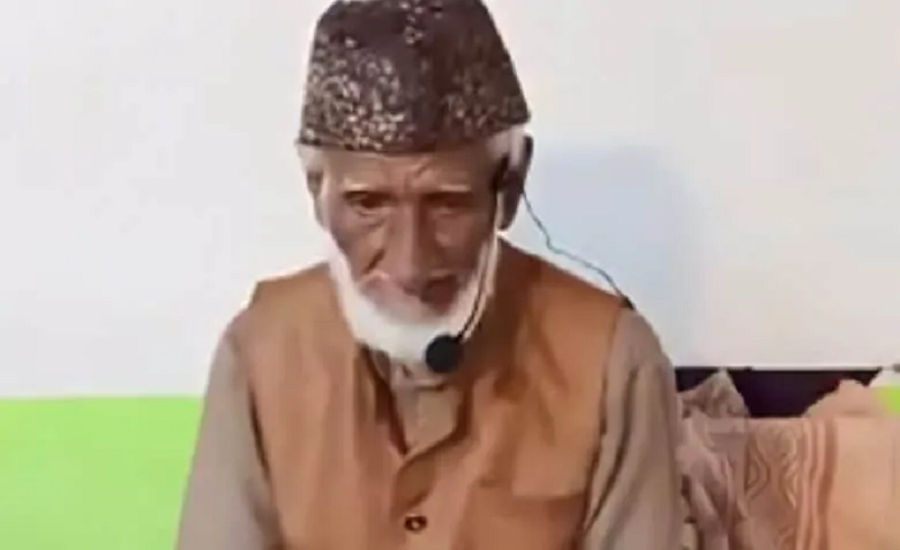

Zahoor Ahmad Shah started the MTI in 1988, when he was 33-years-old, after a song by sufi singer Abdul Gaffar Kanihami, recorded on a small tape recorder, became a huge success. The MTI, gauging the public response, focussed on the Sufi genre.

Their collection included traditional music forms like chakri, folklore sung by a singer with a hoarse voice and supported by a chorus, and wanvun that is traditionally sung by women at festive occasions like marriages. Over the years, the MTI added more genres and forms.

Among MTI’s songs that were popular with the older generation of Kashmiris were an album based on the poetry of Habba Khatoon, the original soundtrack for a movie of the same name, sung by Jameela Khan and songs like Lala Zula Zaliyo sung by Manzoor Shah–now part of weddings, sung by women performing folk dance for the bride or the groom. The song was also appropriated in a 2018 Bollywood movie set in Kashmir, Laila Majnu.

Over the years, MTI roped in most of Kashmir’s famous artists of the time—such as Ghulam Hassan Sofi, Rashid Hafiz, Manzoor Shah, Wahid Jeelani, Deepali Wattal, among others. “We used to work with the artists of Kashmir as well as with Jammu and Pahadi artists. “We even went to border and hilly areas to find the artists,” said Mr. Shah.

The motive was commercial but to also preserve the traditional music and language of Kashmir though its music. “When people used to listen to songs in different languages, I wanted them to listen to the songs in their own language as well,” said Mr. Shah.

Being the first music label in Kashmir, MTI filled a void and gave the artists of Kashmir a platform to record their own songs and reach a larger audience, making their songs available on-demand for the public and reducing the artist’s dependence on radio.

The devotional music MTI recorded also made Mr. Shah feel closer to divinity. “I miss the vibe of being closer to God while recording the sufi music. The vibe was magical. Also, when we started shooting the videos, we used to live in mountains and woods for days,” said Mr. Zahoor Shah.

Their audience comprised all age groups. “I would buy cassettes and listen to it on a device which would play cassettes,” said Aabid Rah, who was ten-years-old when he started listening to the plethora of MTI songs. “I still love listening to Gulzar Ganie, Rashid Hafiz, Hassan Sofi etcetera on their YouTube channel.”

Gradual downfall

With the emergence of newer technologies, MTI switched to CDs in the late 2000s. However, the emergence of flash drives also meant the label’s gradual downfall. “When we started the label, the market was audio then we had to upgrade according to trend and market demand,” said Shah Umer, son of Mr. Shah, who handles the business now.

Piracy became a global concern and the MTI was no exception. Now, it has become easier for music lovers to access music without paying for it, resulting in losses for MTI. “Our business was doing well but with new formats, it faced a sudden fall and then we decided to change our business,” said Mr. Umer Shah.

The father-son duo still remember the older times and miss the vibe of their studio. “I remember singers coming to our studios for one to two weeks and doing rehearsals for recording the audio. I have really good memories of that studio,” he said, adding that he has seen his father recording music in the studio all his childhood.

Mr. Umer Shah was always fond of music and loved being in the MTI’s studio, then located in Srinagar’s Bemina area, as a child. He started working in the studio when he was sixteen-years-old. “I used to spend all the time in the studio and go there from my school. I wanted to handle MTI so I left studies after passing class 12,” he said.

Slowly, guitar and rabab came together and created a different sound and feel but MTI, said Mr. Zahoor Shah, made music according to the taste of Kashmiris. “We never added spices to it but kept it as real as we could,” he said. “Our business was successful as people loved our content.”

However, for some long time listeners, the MTI had also begun losing its essence. According to Mr. Rah, earlier content was meaningful and “the lyrics went down the drain and MTI started producing anything and everything around 2007-2010. There were no more cassettes and the mixing and mastering was eventually replaced by auto-tune”.

Keeping the name alive

The MTI has reduced its footprint in the market and its outlet is now used to sell electronics. It also lost most of its original recordings in the devastating floods of 2014, the few that were not washed away with the water remain stacked in a corner of the electronics store. “I started a YouTube channel last year to keep the name of MTI alive,” said Mr. Umer Shah.

Besides, the MTI has also tied up with prominent music label T-Series and MTI’s collection till 2010 is available on another YouTube channel, T-series Kashmiri Music, said Mr. Umer Shah.

Their YouTube channel, called MTI Studios, has more than fifteen thousand subscribers, and continues to give Kashmiri artists a label and a platform, featuring new artists like Waseem Shafi, Kaiser Hussain, Zuhaib Bhat, Sanam Basit, and the famous Reshma among others.

On 27 May 2020, amid the lockdown prompted by the coronavirus pandemic, the MTI released, a duet by popular wedding singers Ms. Reshma and Mr. Basit, who shot to popularity after his Kashmiri rendition of Champion, “dedicated to the people depressed due to Covid-19”.

The song is a mashup of Ms. Reshma’s popular wedding song, Hay Hay Wesiyee, and other popular Kashmiri songs. The video’s aesthetic cinematography focuses on Ms. Reshma grooving to the music.

It has been more than three decades and MTI is still trying to keep their name and Kashmiri music alive. “We used to get good responses back then and the responses are still the same but I miss the old times,” said Mr. Shah Umer.

source: http://www.thekashmirwalla.com / The Kashmir Walla / Home> Culture> Music / by Gafira Qadir / July 07th, 2020