INDIA :

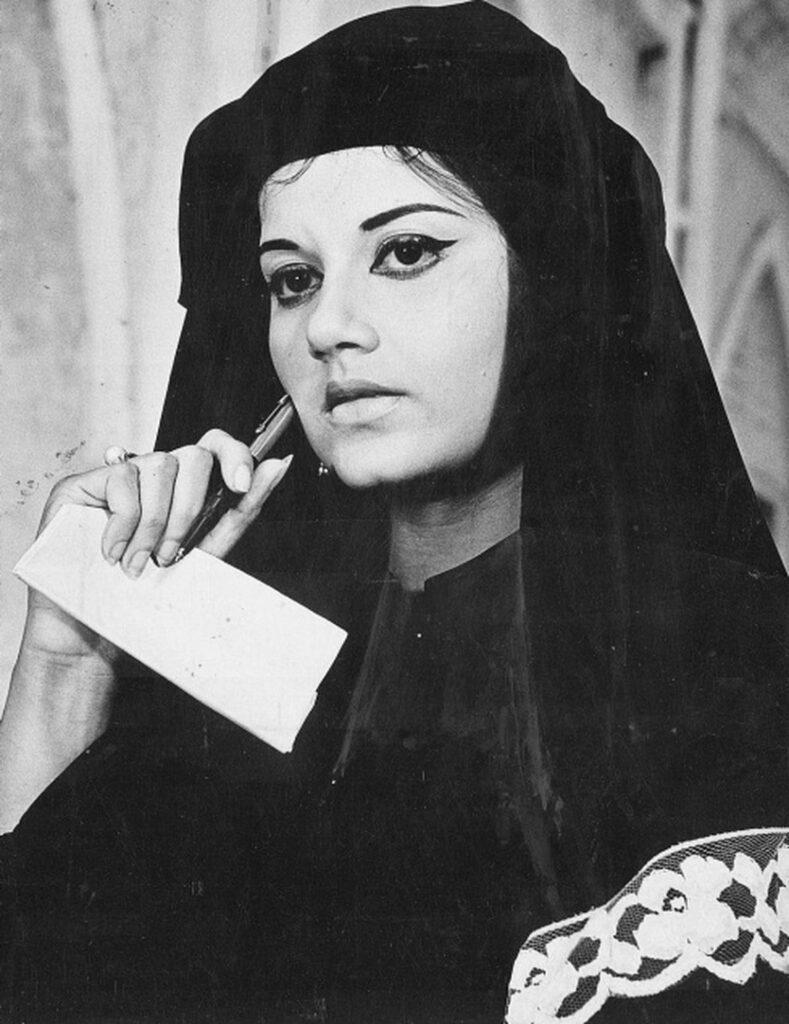

Nazima in Dayar-e-Madina

Till about 30 years ago we used to have a flourishing devotional movie culture in the country. These films were usually made on a shoe string budget with non-stars. Despite their amateurish direction, hackneyed plots and tacky sets, the films did well at the box office largely because of a couple of hummable devotional songs which every film packed in, and a segment of the oft unlettered audience that accepted every thing in the name of faith. If in the ‘60s, we had a film like “Jahan Sati Wahan Bhagwan”, it was followed a few years later by “Ganga Sagar” and “Har Har Mahadev”. The biggest though was “Jai Santoshi Maa” which surprised everybody with its record run at the box office. Many in the audience crossed the line between reel and real by bowing in front of the film’s hoardings, bringing along pooja thalis to cinema halls and the like. The devout lived the film.

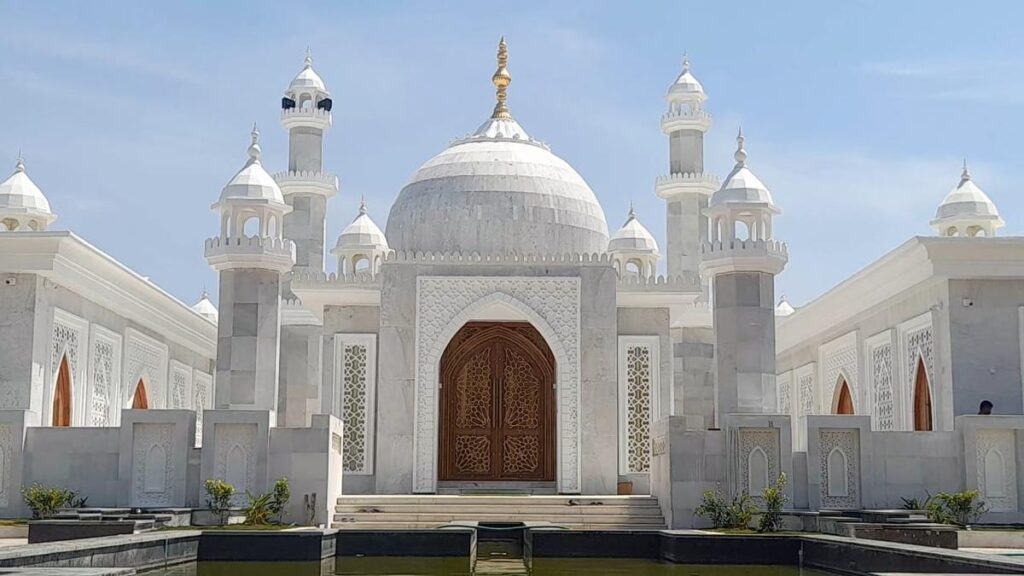

Parallel to this Hindu devotional stream was a sub stream of Muslim devotionals. If Hindu devotionals were usually released in those parts of the cities where immigrant blue collar workers resided, Muslim devotionals, almost entirely predictably, played at show houses near places of Muslim predominance.

This relation between cinema and demography was unique, and lasted till the time a film packed in enough masala or message to transcend boundaries of class or religion. Something which Hindu devotional “Jai Santoshi Maa” did with felicity. “Mere Gharib Nawaz”, “Niaz aur Namaz” and “Dayar-e-Madina” too reaped a rich harvest at the box office.

Incidentally, keeping in mind that a big chunk of the audience – Muslims – stayed away from cinemas in the month of Ramadan, big banners avoided releasing their films during the time of fasting, waiting for the more celebratory mood around Eid. The Muslim devotionals though ran during this time, the assumption being that these films, like the Hindu mythologicals, were not regarded as entertainment but an extension of faith.

The success of “Dayar-e-Madina” was particularly impressive with the Urdu language film even managing a run at a cinema hall like Chanakya, otherwise renowned for playing the best of Hollywood in Delhi’s super elite zone.

Then, in a fine advertisement for the nation’s secular culture, the film often showed at a cinema a week after it had shown “Jai Santoshi Maa”. At Old Delhi’s Jagat cinema too it had a fine run. The cinema was located close to the historic Jama Masjid with a couple of other masjids in the vicinity.

Director A. Shamsheer’s film had a limited run. However, the local clerics sent in an application to the management of Jagat requesting for an extension to the film. They saw the film, not as a ruse of Satan to lead the faithful astray, but as a vehicle for inner satisfaction.

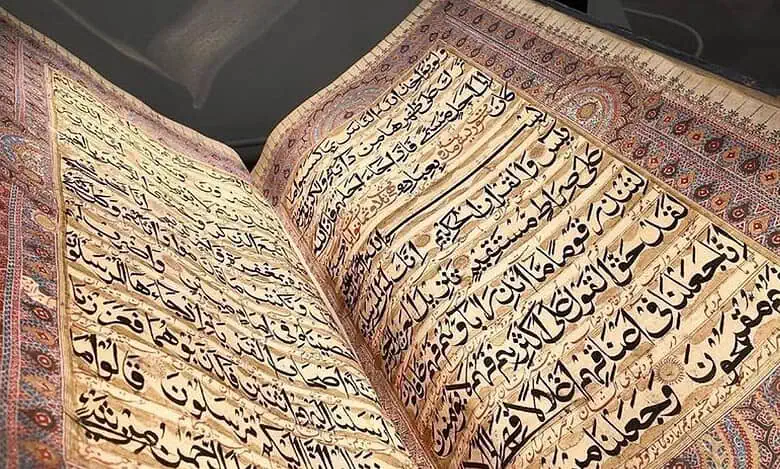

Why not, the film begins with Qari Mohammed Mewati’s complete azan followed by a little lecture on the five principles of Islam. “The life of Huzur (Prophet) is like the Quran. He practised what he preached and preached what he practised. Zakat is the poor due. Pay zakat, it cleans your wealth,” says the school master in customary fashion before being dragged away by other demands of life.

Soon though the film, with commentary by Kamal Amrohi, changes tracks developing into the timeless tale of “twins separated at birth”. Here, two girls go their own ways after having lost their mother at the time of birth. One is adopted by her aunt, the other stays home. One develops into a believer, the other, in a perfect cliché, is all about fashion, tennis, guys and the like. Yet they manage to meet as lovers, as adults, giving a typical twist to the tale. In between Shamsheer remembers that the film is about belief. So, every now and then, he takes recourse to faith; a verse from the Quran here, a reference to a hadith there.

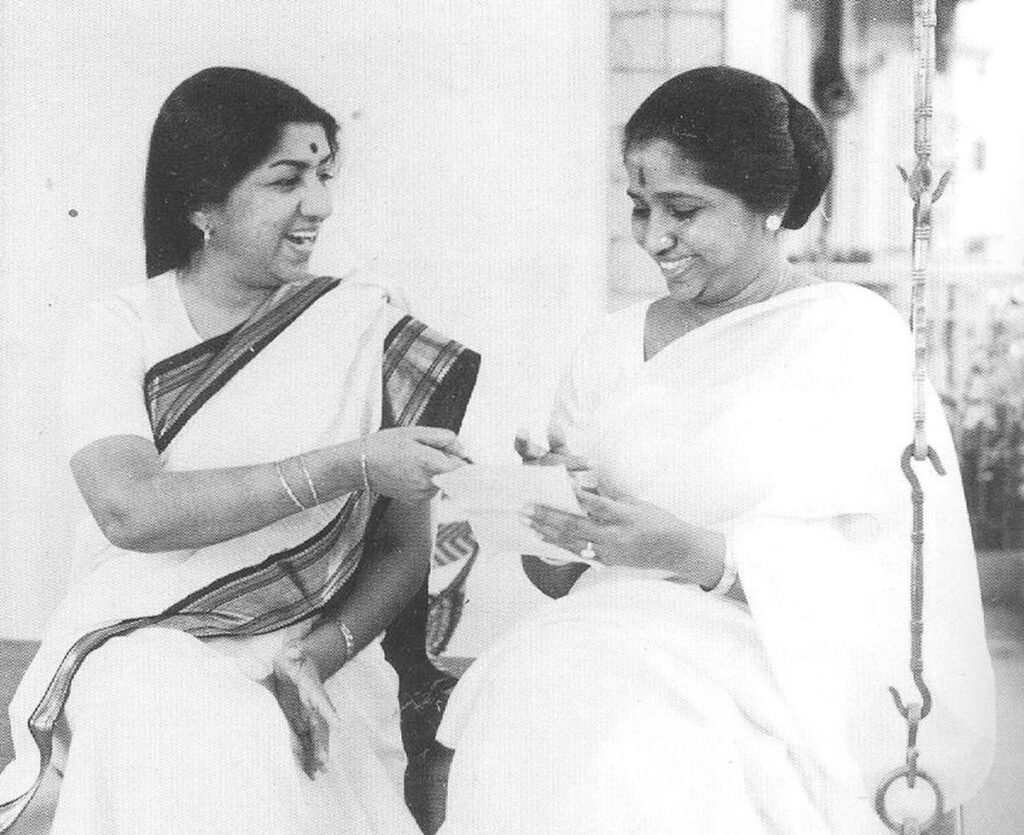

Not to forget the likeable song “Madad Kijiye Taajdar-e-Madina”. Incidentally, the film’s music by Mohammed Shafi stayed on in the memory of cinegoers long after the film’s bow office showing was over. A couple of cassette-sellers in the neighbourhood of cinema chose to play “Madad Kijiye Tajdaar e Madina” in the voice of Mohammed Rafi to attract the faithful. Interestingly, the female version of the song, by Asha Bhonsle, perfectly melodious, met with a lukewarm reception on the streets of Old Delhi.

The film had enough clichés to last half a dozen such ventures: ghararas, burqas, mushairas, sherwanis, paan-chewing men, age-old havelis with lattice work, etc. That it still worked at the box office says as much about the director’s ability to carry a moth-eaten tale as the viewers’ eagerness to watch a Muslim devotional. Not just “Dayar-e-Madina”, many men and women around Jagat waited for the 1973 film “Alam Ara” to grace the hall. No such luck. They learnt their lesson. So in 1977 when “Niaz aur Namaz” was shown at any hall in the vicinity, they trooped along. A devotional could not be missed.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> Friday Review> Blast from the Past / by Ziya Us Salam / July 09th, 2015