Mysuru, KARNATAKA :

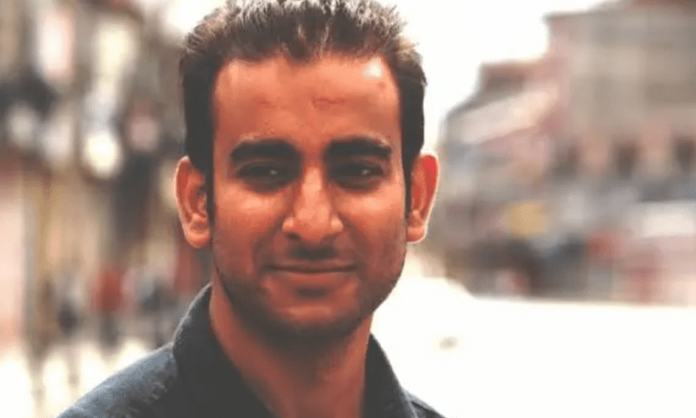

Mysuru-based Director Islahuddin believes in movie-making beyond the ordinary

The Kannada film industry, popularly known as Sandalwood, has recently witnessed a surge in films across diverse genres, breaking away from the conventional commercial ‘masala’ formula. Films like Achar & Co, Daredevil Mustafa, Hostel Hudugaru Bekagiddare, Tagaru Palya and Orchestra Mysuru have been warmly embraced by audiences, proving that the industry is in safe hands with the new generation of filmmakers stepping up to the challenge.

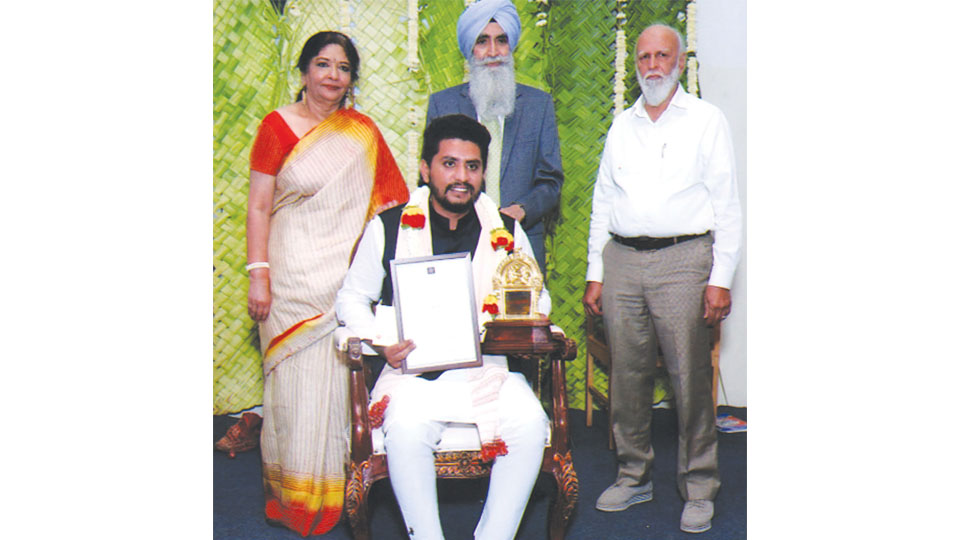

Joining this fresh wave of talent is N.S. Islahuddin from Mysuru, the director of the Kannada film Anna. Despite hardships, Islahuddin successfully directed a few films, including Nodi Swamy Ivanu Irode Heege, starring Rishi.

Known for inspiring many aspiring actors and technicians, Islahuddin is now back with his latest venture Anna, which tells the story of eight-year-old Mahadeva. Set in the 1980s, the film portrays the struggles of a poor family that cannot afford even rice (Anna in Kannada).

Islahuddin also pioneered Kannada’s first-ever crowd-funded film, Jaagadoreyuthade (Spaces for Rent), an adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s play The Lower Depths.

Star of Mysore caught up with the talented moviemaker Islahuddin during his recent visit to Mysuru for a brief chat. Excerpts…

Star of Mysore (SOM): How do you feel about ‘Anna,’ a non-commercial movie, being accepted by all sections of the audience?

Islahuddin: I am elated. Being embraced by all sections of society feels like a blessing. Our movie doesn’t take sides — except for the side of the hungry. ‘Anna’ is merely a metaphor. While rice, as a staple food for billions, holds deep significance, our story is set in the 1980s when rice was a luxury beyond the reach of the common man. Today, ‘Anna’ could symbolise any unfulfilled desire of the underprivileged.

SOM: What inspired you to choose a subject like ‘Anna?’

Islahuddin: The story found me. It is based on a Kannada Sahitya Akademi award-winning short story by Hanur Chennappa, who had previously served as Assistant Director, Department of Kannada and Culture in Mysuru. The team was already in place, and I joined towards the end. I am deeply grateful to the entire ‘Anna’ team for making this an unforgettable experience.

SOM: For a film like ‘Anna,’ it’s often difficult to secure producers and theatres for release. How did you manage both?

Islahuddin: ‘Anna’ symbolises desire. It highlights the gap between ragi and rice and the divide between the haves and have-nots. Basavaraju, our film’s producer, who faced hardships in his youth, was approached by our music director and executive producer Nagesh Kandegala and he instantly agreed to produce the film. The film has turned out exceptionally well and the overwhelming response during screenings gave us the confidence that we have a winner. Even though Basavaraju is a first-time producer, we chose to take this leap of faith on our own.

SOM: With four gold medals in journalism and mass communication, a master’s from the University of Sunderland and having cleared the National Eligibility Test (NET) from the University Grants Commission (UGC), you could have easily settled as a Professor in a reputed university. Why did you choose theatre and films?

Islahuddin: I’ve always liked theatre and cinema and so did my friends. I’ve always valued my friendships and most of my friends are here in my city Mysuru. We are a close-knit group here in Mysuru, bonded by our shared passion for the arts. Our journey began in theatre, but we quickly set our sights on filmmaking.

I took the next step by pursuing my master’s in filmmaking in the UK, then returned to Mysuru to reconnect with my friends. Our primary goal has always been to build a thriving ecosystem for filmmakers right here in our city.

SOM: What are your upcoming projects?

Islahuddin: I’ve been in talks with a few actors, who also happen to be good friends, about directing some scripts I’ve written. Additionally, there are exciting offers from producers interested in bringing my stories to life with me as the director. There’s also an international project in the works, but I’ll reveal more when the time is right. Only time will tell. — VNS

Excelled academically

A graduate in Business Management from D. Banumaiah College, Islahuddin went on to pursue a Post Graduate degree in Mass Communication and Journalism at Manasagangothri, where he excelled academically, bagging four gold medals, including the prestigious Star of Mysore Silver Jubilee Endowment Gold Medal in 2006.

His passion for filmmaking led him to secure a scholarship at the University of Sunderland, where he earned a Master’s in Media Production in 2008. Upon returning to Mysuru, Islahuddin embarked on a challenging 15-year journey to fulfil his dream of directing films.

source: http://www.starofmysore.com / Star of Mysore / Home> Feature Articles / September 12th, 2024