KERALA :

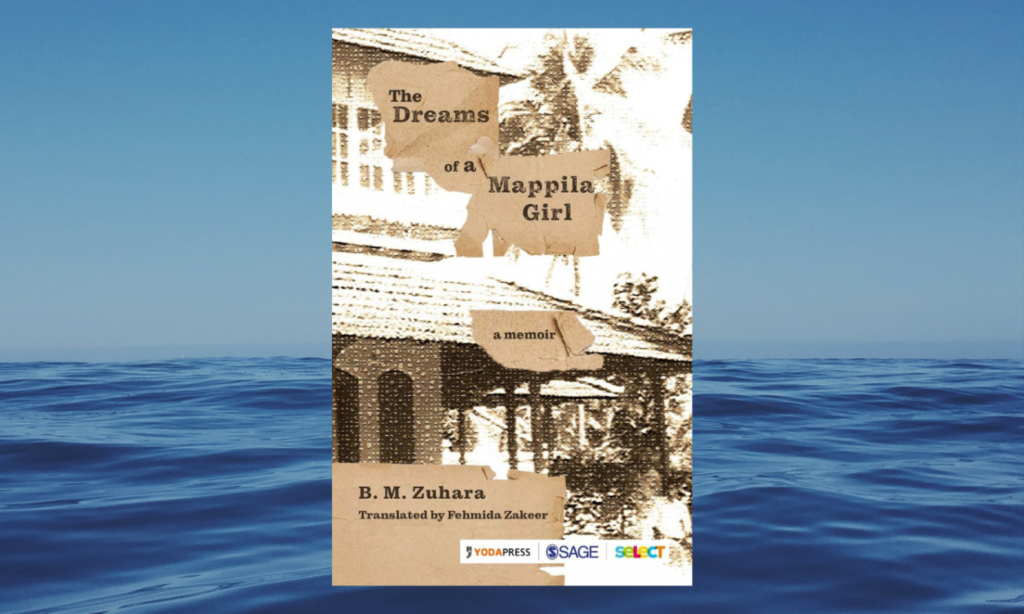

In the preface to her memoir, the author B. M. Zuhara writes, “I grew up at a time when Muslim girls did not even have the freedom to dream.” The Dreams of a Mappila Girl is set at the time when independent India was embracing its new identity as a free nation. It offers a rare portrait of women in Muslim households in North Kerala through the lens of a woman writer. Zuhara showcases how women, bound as they were by the rules of society, still managed to hold key positions in their family and had an important voice in the discussions concerning their lives, contrary to popular perception.

The following piece is an excerpt from Fehmida Zakeer’s translation of the book, soon to be out from Yoda Press.

****

During the holidays, the hall upstairs turned into a playground for the children, who were allowed to play outdoors only in the evenings. Lined by long windows without grills, and furnished only with Uppa’s charukasera and writing table, the hall was an expansive place for us to jump and run and skip and play. Below the glass windows was a cement slab broad enough to be used as a seat, running the length of the hall. If you sat on it and looked out of the window, you could see paddy fields and coconut groves and people out on the road in front of the house.

One evening, I was playing with Achu, the elder brother nearest me in age. Though his name was Assoo, I called him Achu. We were racing cars, or rather matchboxes converted by our imaginations into pretend cars. Since both Achu and I were recovering from a fever, we did not have permission to go out and play with the others, and so we were playing in the hall upstairs. Suddenly I heard the sound of Umma’s medhiyadi on the staircase leading from the women’s section of the house.

In those days, people used wooden footwear indoors. Climbing stairs in a medhiyadi, gripping the peg in the middle with the big toe and the second toe, was a feat in itself. Valippa’s medhiyadi, which he wore when he went out, had leather straps. Uppa preferred to wear shoes when he stepped out of the house. Once a year, Chandu Aashari, the family carpenter, made medhiyadi for the whole family. Achu once broke the small medhiyadi made for me by Chandu Aashari, and how I wept!

Umma did not normally come upstairs in the evenings. I looked enquiringly at Achu when we heard the sound of her footsteps.

‘Umma is going to Kozhikode tomorrow morning. She knows that you will cry and insist on going with her. That’s why she didn’t tell you.’

Even though I knew Achu was trying to provoke me, my eyes started filling with tears. I was five years old at that time, and in class one at school. I missed school frequently because I used to accompany my mother wherever she went. This continued in class two. At the end of each year, Uppa would visit the school and meet the teacher, and I would be promoted to the next class. This was the usual practice.

I closed my brimming eyes and stood there thinking.

Achu spoke again. ‘Umma must have come upstairs to pack her clothes for the trip. You’d better go quickly.’

‘Don’t take my matchboxes. I’ll be right back,’ I called out as I ran to Umma’s room.

‘I told you about Umma’s trip, so now the matchboxes are mine,’ I heard Achu shouting after me, but I decided to ignore his words for now.

When I entered the room I saw the doors of the meshalmarah opened wide. The scent of kaithapoo filled the room. How it lingers, the fragrance of screwpine! The meshalmarah doubled as a table and a cupboard, and was actually a long table with drawers on both sides with space to store things below. Umma called the meshalmarah her clothes cupboard. Umma stored her clothes on one side and the children’s on the other side. In those times, children usually had only one or two sets of clothes, made from lengths of cotton. Trousers and shirts for the boys and chelakuppayam, or frocks, for me.

‘You are packing to go to Kozhikode without me?’ I whimpered.

Umma turned to look at me. ‘The crybaby has arrived!’ she said.

At that, I wailed even more loudly.

I had three nicknames as a child. Karachapetti, Tarkakozhi and Ummakutty. Karachapetti because I cried a lot; I did not know the meaning of Tarkakozhi but when someone called me that, I would put on a sullen look; I actually liked my third nickname of Ummakutty, ‘mother’s darling’. When someone called me by that name, a shy smile would tug at my lips. I liked to sing the lullaby Umma often sang to me. ‘Umma’s little girl Soorakutty, darling little daughter of mine.’

But at that moment, I was not thinking about the nicknames or Umma’s special song for me.

‘If you go without taking me with you, by God, by the Prophet, I will not go to school till you come back.’

‘Moideen will tie your hands and legs and take you to school,’ Umma said as she placed her clothes in a cloth bag fitted with wooden handles.

Moideen was the caretaker of our house, and all the children were scared of him. But even though he put on a stern face when any of us misbehaved, he really liked us. Whenever I cried and created a fuss, he would arrive and take me to the pond at the back of our house. He would get into the pond and pluck a lotus for me or teach me how to make toys with lotus leaves.

‘If I complain about a stomach ache, Ummama will not send me to school,’ I said, pouting.

‘This is too much. Don’t you want to learn to read and write? If you follow me around all the time, how will you learn your lessons?’

‘I don’t want to,’ I said resolutely.

‘Don’t imagine I’ll take you this time, Soora. If you hide inside the car, I will drag you out.’

Usually when it became clear that Umma would not take me with her on a trip, I would hide between the seats in the car without even having changed into an appropriate outfit. It did not occur to me that my grandfather, seated in the charukasera on the verandah, the driver, and the servants busy in their tasks would all notice my presence. I thought I was fooling Umma by hiding in the car. When Umma came out of the house and went up to the car, Valippa would jokingly call out, ‘Mariya, be careful, there is a cockroach in the car.’

Umma would understand immediately. She would get into the car and pinch my ear and say, ‘Don’t get smart with me. Get out of the car.’

I would hug the seat and wail loudly.

Valippa would say then, ‘Take her with you. She’s a baby after all.’

‘Baby indeed, she’s over five years old. You are all spoiling her.’

And I would get to accompany Umma to Kozhikode once again. Umma’s younger sister lived in Kozhikode and, to us children, her house was a source of wonder. Umma had to see the doctor in Kozhikode every three months and she would drop in at her sister’s house when she made the trip.

Now Umma ignored my wails and placed the bag filled with her clothes on the table. Then she went downstairs. Sobbing loudly, I followed her.

‘Why is the baby crying?’ Ummama called out from below the stairs.

‘If she complains of a stomach ache tomorrow morning, don’t allow her to take the day off from school, Elama.’

When Umma was fifteen years old, her thirty-year-old mother, nine months pregnant, died. Later, Valippa married again. Our present Ummama was his second wife. I understood all this only later. Even though my mother and her siblings called their stepmother Elama, Ummama treated them as if they were her own children.

Ummama intervened on my behalf now. ‘Take her with you, Mariyu. If you leave her here, she will raise the roof with her crying.’

By then we had climbed down the stairs.

Umma ignored me and asked Ummama, ‘Is Uppa sitting on the verandah?’

‘He was asking for you. He just sent Assan to look for you.’ Assan, the handyman, was Moidyaka’s son.

Every evening Umma and Ummama went to the verandah to keep Valippa company. This was the only time they were allowed on the verandah.

‘Aren’t you coming?’ Umma asked as she made her way outside.

‘You go on. I’ll come soon,’ Ummama said, walking towards the eastern side of the house where the bathrooms were located.

As Umma made her way to the front of the house, I followed close behind, sniffling and crying.

‘Soora, don’t irritate me. If you don’t stop I’ll lock you up in the kunhiara. I’m warning you.’

Kunhiara. As soon as I heard that word, my wails dwindled to a whimper. Kunhiara was the small room where the sparingly used big and heavy copper and brass utensils were stored. The room was dark even during the daytime and was a haven for cockroaches, moths and rats. I was not really scared of the cockroaches, the moths, the rats. What terrified me was the tomcat installed in our house to catch the rats. Its glowing eyes struck terror in my heart. To me, spending time there was like being in hell, and once locked inside I would remain there until the servants came to rescue me. I was still sobbing when we reached the verandah.

‘Chu, why are you laughing?’ asked Valippa.

My grandfather called me Chu.

‘Your darling Chu cries all the time,’ Umma said crossly.

‘Don’t say that, Mariya. Look at her smiling now. She looks so beautiful.’

On hearing this, in spite of the tears streaming from my eyes, I attempted a smile.

‘That’s my brave girl. Come here.’ Valippa beckoned to me. ‘If you massage my legs, I’ll give you a mukkal.’

Forgetting about the trip to Kozhikode, I walked towards the charukasera where my grandfather sat with his legs hoisted over its elongated armrests. I massaged his legs one by one with my small hands.

‘I want the coin with the hole.’

In those times, one pice coins came with a hole and without. I preferred the ones with the hole. I dropped all the coins I got from Valippa into a powder tin which had its top cut open with a knife.

By then, Ummama had reached the verandah. Ummama would sit on the bench and Umma would stand by the door as they talked about the events of the day with my grandfather. I listened to them talking as I pressed Valippa’s feet, directing smug looks at my mother and feeling like the valiant Unniarcha.* Absorbed in conversation, Umma too seemed to have forgotten the whole episode.

***

* Unniarcha is a mythological warrior woman celebrated for her fearlessness, immortalised in the vadakkan paatu, the ballads of the region.

Translator’s Bio

Fehmida Zakeer is an Independent writer with bylines in several publications including, The Bangalore Review, The Hindu, Al Jazeera, Reader’s Digest, National Geographic, Whetstone Magazine, NPR. Her fiction has appeared in publications such as The Indian Quarterly, Out of Print Magazine, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, Asian Cha, among others. A story of hers was placed first in the Himal South-Asian short story competition 2013, and another was chosen by the National Library Board of Singapore for the 2013 edition of their annual READ Singapore anthology.

___________________________________________

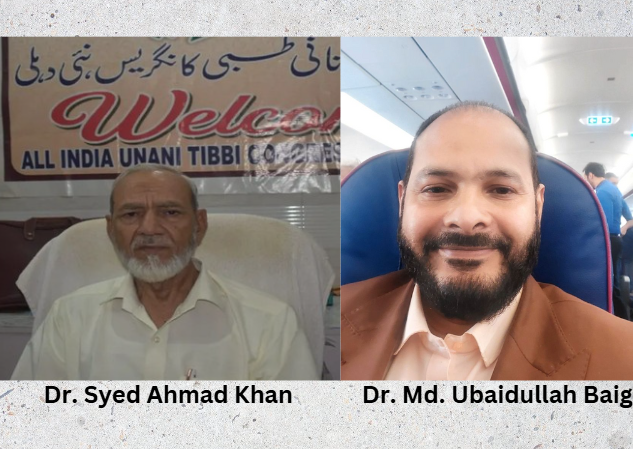

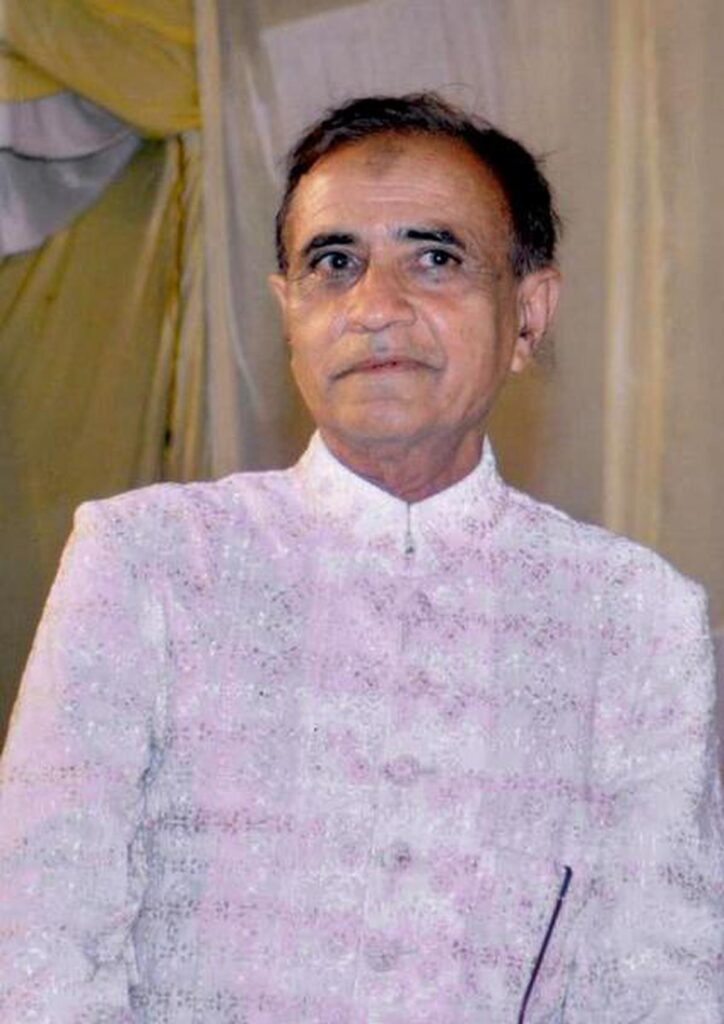

B. M. Zuhara

BM Zuhara has written novels and short stories and is the first Muslim woman writer from Kerala. She won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award for her contribution to Malayalam literature in 2008 and has received awards such as Lalithambika Antharjanam Memorial Special Award, Unnimoy Memorial Award and the K. Balakrishnan Smaraka Award. Her novels, Iruttu (Darkness), Nilavu (Moonlight) and Mozhi (Divorce), have been translated into Arabic while the English translation of Nilavu was published by the Oxford University Press in an anthology titled, Five Novellas. She translated Tayeb Salih’s Wedding of Zein and Naguib Mahfouz’s Palace Walk into Malayalam.

______________________

source: http://www.bangalorereview.com / The Bangalore Reviews / Home> Non-Fiction / by B M Zuhera / July 2022