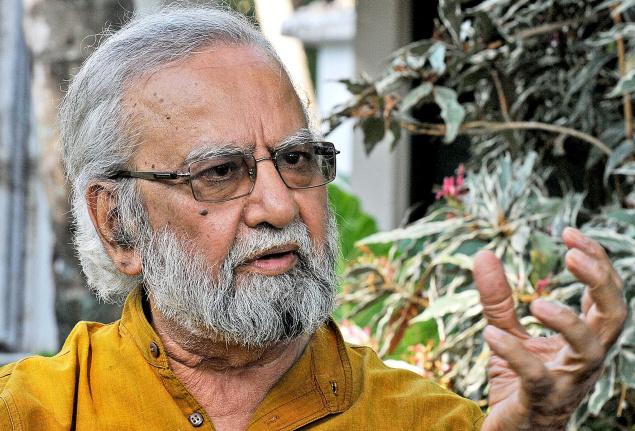

Gulam Mohammed Sheikh creates images of mystics alongside demons

The idea of the Ram Janmabhumi came to artist Gulam Mohammed Sheikh from a mural in Mattancherry Palace depicting three mothers: Kausalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra giving birth — a majestic portrayal of motherhood, as he describes it.

The dapper artist, who defies labels, borrowed the image and incorporated it alongside a picture of the Babri Masjid demolition in one of his ‘Shrine’ series of works, shaped like a Rajasthani ‘Kavad’, a portable miniature box-shrine, in the aftermath of the darkest day of Post-independence India.

He was in Kochi on Monday to take part in the ‘Let’s talk’ programme organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation. In a conversation with The Hindu at Fort Kochi, Mr. Sheikh said the ills that gnawed at Indian society today boiled down to beliefs. Hence you also see demons in his shrine besides great mystic poets like Kabir Das, as if in contrast. “Our great poets have rarely been painted, you know,” points out the art historian, poet and teacher, who exerted a profound influence on the Indian art scene by mentoring several generations of artists who studied Fine Arts at the University of Baroda.

In the early 1960s, when Ratan Parimoo went on an academic sabbatical, then dean N.S. Bendre suggested Mr. Sheikh, still doing his post-graduation, teach in junior classes. He went on to teach art history, which he continued even after his return from the Royal College of Art in London. “Though trained as a painter, I was dabbling in art history as a member of the faculty. I was teaching the ‘story of art’, which was compulsory for students in all fine art disciplines. In a smaller institution, you have instruction at a personal level. It was a great learning experience for me, too, as they were all from different background and faced different types of problems…For a practising painter, the greater challenge was to keep yourself apart and enter into the mind of another artist all the same! But I found the challenge rather fulfilling. I also learnt to articulate myself,” he says.

Beat generation

It was the era of the Beat generation and language was being radicalised. It all came to a point where it hit the wall, appoint of no return. In our case, we were looking up to cinema, film-makers like Fellini, Godard and Bunuel for inspiration and were eager to discover a new idiom for creative expression, he says.

On return to India after hitchhiking across Europe, he saw his old pals doing different things. He went around the country and was struck by the tradition of Indian narrative painting. “I felt that the most traditional art is regional and personal. When you are personal you become confessional.”

Along with Bhupen Khakhar, he stumbled upon the idea of evolving an idiom to contextualise their times. While Khakhar turned to popular art of India to develop his language, Mr. Sheikh fashioned an idiom for ‘wanderlust’.

On an off, Mr. Sheikh dabbed in Guajarati poetry and prose as well. “Poetry and painting can coexist. Some things can only be written while some others can only be painted,” he says, insisting that he is open to all genres. “What is important in a work is how you articulate it.”

Even before magical realism and fragmented narrative found examples in Indian English writings, Khakhar’s and Sheikh’s works explored those.

‘Going Home’, a series on home just happened after his return from England. Based on the notion of home (originally, Surendranagar in Kathiawar where he spent the first 18 years of his life), he realised that ‘home’ was an idea he kept returning to, as it changed continuously. “There are homes; there are homes that you yearn for and those that don’t let you go,” he says.

In modern times, when art became a commodity post-liberalisation and communalism became endemic to society, he offered resistance by way of his works. “You got to retain your sanity, acutely aware as you are that we as a society are capable of destroying ourselves. But it’s a collective battle. In fact, it is a fantastic challenge when all spheres are appropriated by fanatical forces. You don’t do activism. But every artist worth his grain will sympathise with the victim and you gain strength from inside. There’s always a way out,” he says.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> Cities> Kochi / by S. Anandan / Kochi – March 18th, 2014