SOUTHERN INDIA / SOUTH AFRICA :

By Nikhil Mandalaparthy. Nikhil is a journalist, community activist, and consultant focused on religious pluralism and social justice in South Asia and North America. He is the curator of Voices of Bhakti, a digital archive that showcases translations of South Asian poetry and art on religion, caste, and gender. He recently served as Deputy Executive Director of Hindus for Human Rights and is currently conducting research as a 2024-25 Luce Scholar.

Editor’s Note: This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

___________________________________

kitne pyare hai yeh badshah jis pe hum marte hain

yeh haqeeqat hai tasawwur mein unka deedar karte hain

unka roza hai beshaq maqaam-e-madad

hum ghareeb ki taqdeer ko acche mein badal dete hain

How loving is this Badsha whom we “die” for

The truth is: in our imagination, it’s him we see

Without a doubt, his tomb is the destination for help;

He changes our unfortunate destinies to good.

– Iqbal Sarrang (2002)

(Translated by Goolam Vahed, with edits

_______________________________

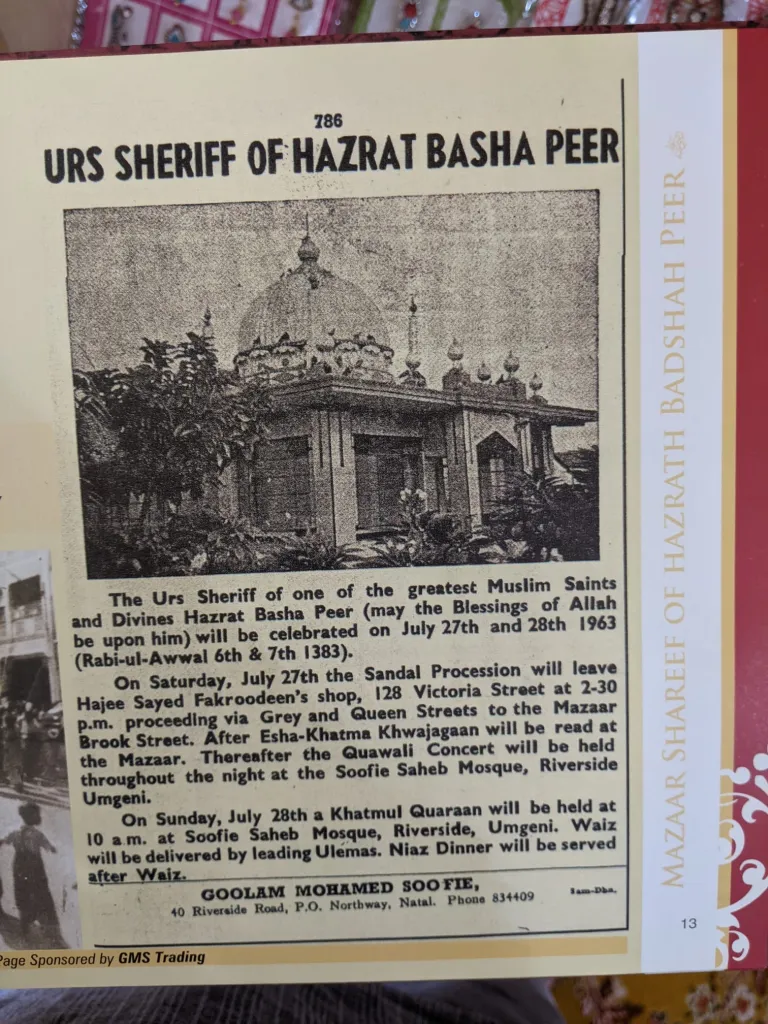

Mazaar of Badsha Peer, Durban, South Africa / Source: Author

In the historic Brook Street cemetery in Durban, South Africa, a gleaming white and gold structure towers over dozens of tombstones. This is the mazaar (tomb) of Sufi saint Badsha Peer. Thousands of miles from his birthplace in southern India, he is said to have found his final resting place here in 1894.

Inside the shrine, an inscription declares that this is “The MAQAAM (Resting Place) Of The King Of Africa – HAZRATH SHAYKH AHMED BADSHA PEER (RA)”.

Visiting Badsha Peer’s shrine challenged much of what I was told about South African Indian identity and history. In my conversations with South African Indians, I was told that most Muslims in the community were Gujarati or Konkani, and that most South Indians were Hindu or Christian. But here I was, at the shrine of a Muslim saint who was also South Indian. I was intrigued—and confused.

Digging deeper, I found that the story of this “King of Africa,” Badsha Peer, is a tale of multiple migrations, across the Deccan, South India, and beyond. His story involves Konkani Muslims and Hyderabadi Sufi teachers traveling to colonial Bombay, and Tamil and Telugu indentured workers making the long and treacherous journey from Madras to South Africa.

Tracing the story of Badsha Peer—and Soofie Saheb, the man who popularized his memory—shines light on how Indian religious, linguistic, and regional identities were transformed in the Deccan and South Africa, during the colonial period and through indenture and migration.

Locating Badsha Peer in History

Pinning down the historical Badsha Peer is difficult. Goolam Vahed, a scholar of South African Indian and Muslim history, describes the saint as having a “sketchy biographical profile and unclear genealogy”.

Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed write of a Sheikh Ahmed who arrived from Chittoor (modern-day Andhra Pradesh) or Arni in North Arcot district (modern-day Tamil Nadu) on the first ship from India, the SS Truro, which arrived on November 16, 1860. On the other hand, Nile Green, a historian of Indian Ocean Muslim networks, points to a Sheik Ahmed from Machilipatnam (modern-day Andhra Pradesh) who arrived a month later, in December 1860, on the Lord George Bentinc.

Either way, according to oral tradition and popular anecdotes, Badsha Peer is remembered as arriving with the first indentured laborers from India. A man of great spiritual power, he is popular for the miracles he performed on the colonial sugarcane plantations, such as accomplishing his tasks in the fields while simultaneously meditating all day.

According to Nile Green, South African oral traditions declare that he was “released early from his indenture due to ‘insanity’”, which was later given a Sufi interpretation as “spiritual rapture (jazb).” Following his release, he is said to have lived the rest of his life as a faqir (mendicant) around the Grey Street mosque until his death in 1894.

Muslims like Badsha Peer made up about 10 percent of the approximately 152,000 Indians who were brought to South Africa as indentured workers; over 80 percent were Hindu. Around 44 percent of indentured Muslims departed from Madras, and among these workers, over 60 percent came from four areas: Arcot (31 percent), Malabar (14 percent), Madras (11 percent), and Mysore (7 percent).

Indentured Muslims, like Hindus, largely came from marginalized castes. In his shrine, Badsha Peer’s caste is simply listed as “Muslim” and “Mohamedan”, which is how around half of indentured Muslims named their caste according to immigration records.

However, Desai and Vahed mention Badsha Peer’s caste as julaha (weaver). He may have been from the Dudekula community , a Telugu-speaking Muslim caste associated with weaving and cotton cleaning.

Soofie Saheb and His “Overpowering Influence”

Shrine of Badsha Peer, Durban, South Africa / Source: Author

The reason that Badsha Peer is remembered today is due to the efforts of a non-indentured Indian migrant. This pivotal figure is Shah Ghulam Muhammad (d. 1911), popularly remembered in South Africa as “Soofie Saheb.”

Soofie Saheb was born into a Konkani Muslim family in the town of Ibrahimpatan in Ratnagiri district. The family held a high social status on account of its claim to descend from Abu Bakr, the first caliph of Islam. After studying in Kalyan, he departed for Bombay. Nile Green situates his move within “a much larger migration of Konkani Muslims to the city that had taken place over the previous decades”.

In the early 1890s, Soofie Saheb became a disciple of Habib ‘Ali Shah (d. 1906), a Sufi teacher of the Chishti order. Habib ‘Ali Shah himself was a migrant from Hyderabad who developed a following primarily among Konkani Muslims in Bombay, particularly workers around the Mazgaon dockyard. In 1895, Soofie Saheb was instructed by his teacher to go to South Africa to spread the message of the Chishti order to the indentured Indian population.

Soon after arriving in Durban in 1895, Soofie Saheb “encountered a situation of close proximity and mixing between Muslims and the large majority of Hindu laborers,” as anthropologist Thomas Blom Hansen writes . Faced with the fact that “Muslims participated widely in Hindu rituals and festivals”, Soofie Saheb began to promote a more “proper” Islamic identity for indentured Muslims. Similar efforts would soon take place among the Hindu community as well, led by Arya Samaj missionaries like Bhai Parmanand and Swami Shankaranand.

One of the first actions of Soofie Saheb in South Africa was to build a shrine over Badsha Peer’s grave, which he is said to have identified through a dream or vision. Shortly afterwards, in April 1896, he purchased a plot of land on the banks of the Umgeni river, upon which he built a complex that included a mosque, khanqah, madrasa, and Muslim cemetery.

Interestingly, the legal documentation for this purchase was prepared by a young Gujarati lawyer who had arrived in South Africa just a few years prior: Mohandas K. Gandhi. Vahed writes that “Between 1898 and his death in 1911 Soofie Saheb built 11 mosques, madrasas and cemeteries all over Natal.”

Reimagining South Asian Languages and Religions in South Africa

A book published by Soofie Saheb’s madrasa in 1970 includes this quote by a Hindu observer: “there were many Tamil-speaking Muslims who, but for the recitals of the Koran, were by tradition and culture typically South Indian. Soofie Saheb’s mystic personality had an overpowering influence on the Muslim community widely scattered.” (emphasis mine)

This framing positions South Indian and Muslim identities as mutually exclusive, with the suggestion that shifting towards a more explicitly Muslim identity necessitated shifting away from South Indian culture. The framing also implicitly links South Indian and Hindu identities together.

What was the nature of Soofie Saheb’s “overpowering influence” among indentured Muslims in South Africa? As Nile Green has noted, Soofie Saheb promoted the Urdu language as core to Muslim identity, even though few indentured Muslims spoke the language.

Green argues that Soofie Saheb was simply following “specific currents of linguistic change in his own Konkani community in India, in which the use of Urdu spread significantly during the early twentieth century, partly as a result of migration” from the Konkan coast to Bombay. Similar developments had taken place elsewhere in the Deccan, such as the rise of Urdu in Hyderabad State in the 1880s as the prestige language of education and social status.

Soofie Saheb’s efforts made Badsha Peer the most revered Sufi saint in South Africa. At the same time, he promoted a cosmopolitan, Urdu-centric Muslim identity that likely would have been unfamiliar to Badsha Peer himself, as a Telugu- or Tamil-speaking indentured Muslim.

These shifts were perhaps aided by the fact that in decades following Soofie Saheb’s death in 1911, many South Indian associations in South Africa adopted explicitly Hindu orientations.

For example, a year after the Andhra Maha Sabha of South Africa was formed in 1931, the organization became an affiliate of the South African Hindu Maha Sabha. The Andhra Maha Sabha’s logo is a Telugu-script Om, and the organization’s headquarters in the Indian township of Chatsworth includes an elaborate Venkateswara temple, which was built in 1983.

Thus, on one side, Telugu cultural associations in South Africa defined Telugu and Hindu identities as synonymous, while Muslim leaders like Soofie Saheb consolidated an Urdu-oriented Muslim identity.

South Asian Legacies: Shared Devotion at Badsha Peer’s Shrine

Interior of the Shrine for Badsha Peer / Source: Author

Although Badsha Peer is remembered as coming from Andhra Pradesh or Tamil Nadu, Soofie Saheb’s emphasis on an Urdu-centric Muslim identity means there is little to no visible South Indian influence in the rituals and practices associated with his shrine today.

And yet, despite Soofie Saheb’s activities to consolidate a distinct Muslim identity among indentured Indians, Badsha Peer’s shrine became a site for prayer, pilgrimage, and worship for Indians across regional and religious identities. In a way, his shrine provided a conduit for older South Asian practices of multi-religious devotion, such as reverence for Sufi mazaars and dargahs.

From the earliest years of the shrine, non-Muslim devotees played a role—Goolam Vahed notes that in 1917, “A corrugated iron structure was erected by a Hindu, Bhaga, around the dome” of the shrine. In 2002, one of the qawwali groups performing at the saint’s urs (death anniversary) was led by a Hindu singer.

Community archivist Selvan Naidoo, director of the 1860 Heritage Centre, recalls that “In my early childhood days, such was the power of this place that my staunch Tamil mother would often take us there to pray at this great place of indentured reverence.”

This reverence for Badsha Peer continues to this day. Mark Naicker, an interfaith activist in Durban from a Catholic family, shared with me that “sometimes you hear Hindus also go to Badsha Peer … when people have a baby, they would go to that shrine” to seek blessings.

It has been over 160 years since Badsha Peer and the first indentured Indians set foot on South African shores. He is a unique figure in South African Indian history. Unlike most indentured Indians, he was Muslim. Unlike most Indian Muslims in South Africa, he was from southern India. And unlike nearly any other indentured Indian Muslim in South Africa, he is revered as a saint whose power is manifest even to this day.

Badsha Peer’s story, intertwined with that of Soofie Saheb, provides us with a glimpse into how Indian identities were transformed and reconfigured in South Africa. “Muslim” and “South Indian” identities took increasingly divergent paths. And yet, despite these shifts, his memory lives on, drawing devotees from across religious and regional backgrounds who seek the blessings of this “King of Africa.”

source: http://www.maidaanam.com / Maidaanam / Home / by Nikhil Mandalaparthy / June 17th, 2024