Nawab Safdarjang’s tomb used to be a place of halt for the Tazia procession from the Walled City before it ended at the Karbala in present-day Jorbagh

Many have admired Safdarjang Tomb as the last flickering lamp of Mughal architecture but it was left to Dulcie Hamilton, a passing-by travel writer from Melbourne, to remark that it was like “an inverted lotus, just the opposite of the latter-day Baha’i Lotus Temple” (in an age when the Lotus symbol is politically abloom). Both the structures incidentally have an Iranian link as the founders of the Baha’i faith, the “Bab” and Bahaullah belonged to Iran while Nawab Safdarjang also had Iranian antecedents. For this reason, his last resting place occupied pride of place in Jorbagh, the Shia cemetery that extended up to it at one time and was second in importance only to the (Hazrat Ali) Qadam Sharif shrine set up by Qudsia Begum, the wife of Mohammad Shah in the 18th Century. Safdarjang was the Vazir at her husband’s court and later that of her son. It should be no surprise, therefore, that the tomb took pride of place during the Moharrum mourning for Imam Hussain.

The tazia processions that came from the Walled City made their first halt at the palace of Mahabat Khan, behind his contemporary Abdun Nabi’s masjid in the present ITO area and the next one at Safdarjang’s Tomb before finally ending at the Karbala. Mahabat Khan’s mahal does not exist now but his grave is there in Jorbagh.

Another interesting fact that few know about is that Safdarjang’s first Urs or death anniversary saw many Shia divines arriving in Delhi from Oudh and surprisingly enough, a qawwali was also held at the behest of his son and successor, Nawab Shujauddaulah who was reputed to have the longest moustaches in the Mughal empire. He aided Ahmed Shah Abdali in the third Battle of Panipat in which the Maratha confederacy led by the imperious Sadashiv Rao “Bhau” lost. After that Shujauddaulah’s clout in the Mughal durbar increased with the arrival in Delhi from Allahabad of Shah Alam (designated emperor by Abdali).

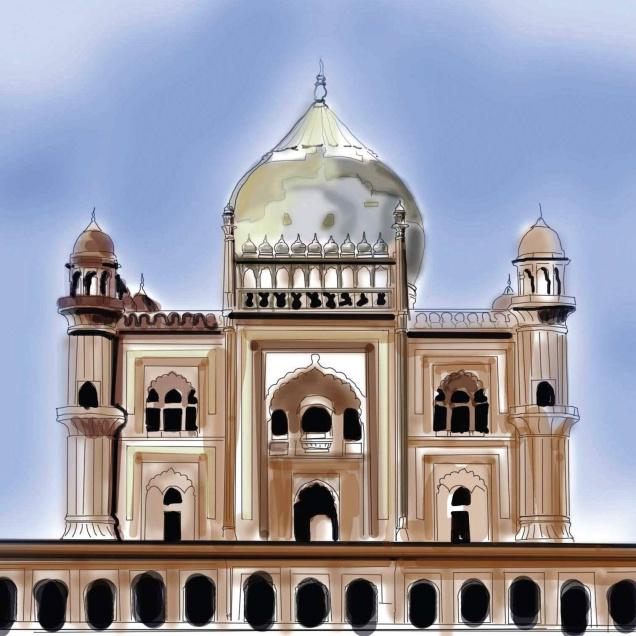

Safdarjang’s mausoleum, designed on the pattern of Humayun’s Tomb, is a poor imitation. The three-storey tomb in fawn-coloured stone also bears a faint resemblance to Akbar’s mausoleum at Sikandra, but lacks the magnificence of the latter. Even so it is an interesting monument, situated amidst a garden of 300 square yards, and enclosed by a wall at the corners of which stand octagonal towers and a central dome, rising above a 16-sided drum.

Arcaded pavilions, named Moti Mahal, Badshah Prasad and Jangli Mahal, have been, constructed on the northern, southern and eastern sides, like the pavilions in the outer quadrangle of the Taj. It is believed that these were meant for the accommodation of nobles who visited the mausoleum. The tomb has a carved cenotaph in the central chamber within which is another chamber containing two unmarked graves, both with earthen mounds above them. In it lie buried Mirza Muquin, Abul Mansoor Khan Safdarjang, and his wife Banu Begum. The monument was built by Shujauddaulah at a cost of Rs.3 lakhs with a lot of marble and other material being pinched from the mausoleum of the Khan-e-Khanan and other Mughal buildings.

Safdarjang was the head of the Shia Irani Party at the court of Ahmed Shah (1748-1754). His opponents were the leaders of the Sunni Turani party headed by Imtiaz-uddaulah and Imadad-ul-Mulk. Safdarjang, who had succeeded Burhan-ul-Mulk as Nawab of Oudh, died at Faizabad in 1754 and his body was brought to Delhi, for though he had to leave the Mughal court in disgrace after trying to play kingmaker, he nevertheless pined for his days of grandeur in the Capital and desired to be laid to rest there. His mausoleum has a mix of Mughal, Rajput, Iranian and Egyptian architectural patterns jostling for space.

Even so, it attracts a lot of tourists but these days, the water channels – a notable feature – are dry which is a turn-off. The renovation work has been done only on some portions with others are still badly in need of repairs. When one visited the tomb recently under overcast skies, one wondered if yesteryear music ‘mehfils’ could be revived and tazia processions made to converge on it either at Moharrum or Chhelum for the halim dish break that used to replenish the fatigued ‘Akharas’ or sword and lathi-wielding squads in the past. One thing that Safdarjang couldn’t have dreamt about is that 261 years after death his memory would be enshrined not only in the Maqbara but also in the airport, road, hospital and enclave named after him by a generous posterity which only has a nodding acquaintanceship with him.

The author is a veteran chronicler of Delhi.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by R.V. Smith / March 15th, 2015