KERALA :

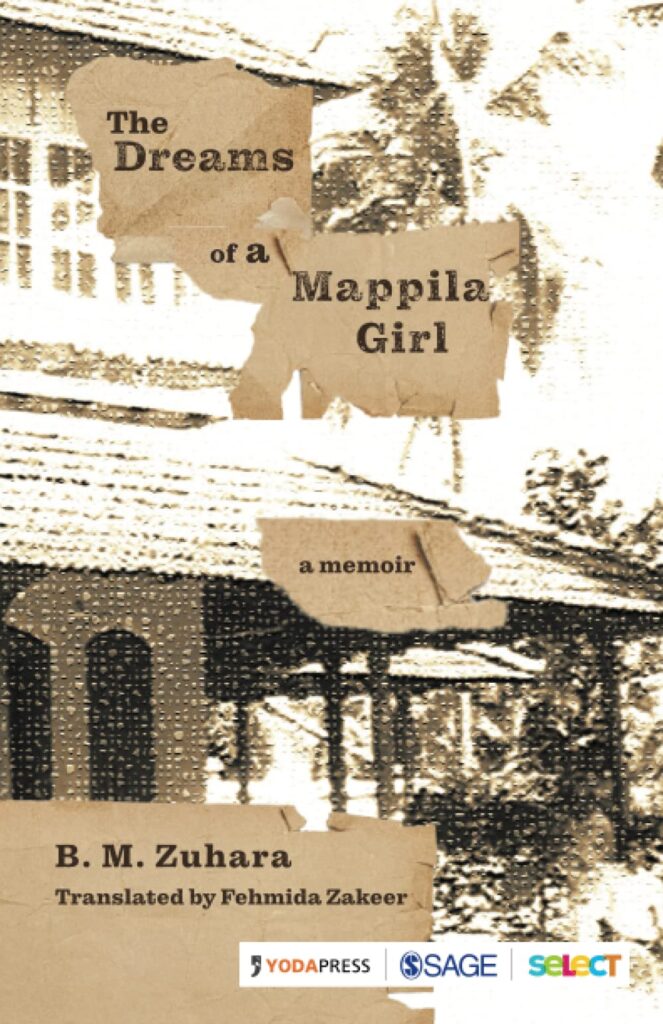

B.M. Zuhara is a writer and columnist from Kerala, a Sahitya Akademi awardee who writes in Malayalam. Her book The Dreams of a Mappila Girl: A Memoir, which was recently translated and published in English, traces the childhood years of the writer, growing up in the village of Tikkodi in rural Kerala as a young Mappila girl from the Muslim community in post-Independence India.

In the Preface, the author wonders if her work is a “story, or a novel, or a memoir”. The only conclusion that one can perhaps draw as one reads on is that it could be any one of them, and it could be all of them. It is a truth universally known but often unacknowledged that classification of works – fiction and non-fiction, into various genres, is done primarily for the sake of convenience. So while the autobiographical narrative is hard to miss, the memoir also reads like a novel, almost like a bildungsroman – a novel that traces the journey of a protagonist from childhood to adulthood; though in this case, the memoir ends with young Soora moving away from her home in Tikkodi to the city of Kozhikode.

Lifewritings

A memoir can be understood as a narrative written from the perspective of the author, focusing on a certain period of his or her life. Unlike an autobiography, it does not cover the entire life span of the author. In fact, increasingly so, the term lifewritings is being preferred over autobiography when the writing revolves around the life of a woman. While autobiographies are seen as concerned with the journey through which one attains a sense of identity or autonomy of the self; lifewritings looks at identity as relational. It is a significant difference because women in a patriarchal society tend to define themselves in terms of their relationships and therefore the impact of relationships on how women see themselves, define themselves, is to a great extent different from the journey undertaken by men to arrive at a notion of the self.

As the memoir unfolds, we meet Soora, as the writer is referred to by all, surrounded by a large, relatively affluent family with complex dynamics. From the beginning we see Soora as a sensitive child, one who is prone to bursting into tears at the slightest provocation, something she is often teased about. The real and perceived slights that Soora is subjected to, are primarily targeted at her physical appearance, specifically her dark complexion and her tendency to cling to her mother.

But paradoxically for a seemingly timid child, Soora’s propensity to constantly question what is established as normative behaviour for a girl earns her the nickname of “Tarkakozhi” – one who argues. What these contradictory impulses perhaps reveal is a girl who is overwhelmed by the big and small battles she has to constantly fight, a life burdened by gendered expectations, yet a girl whose deepest desire is to be like Unniarcha, a mythological woman celebrated for her fearlessness whose ballads Soora grows up listening to.

It’s a woman’s life

Certain details, such as that of Soora’s grandmother passing away at the age of 30, when Soora’s mother was 15; or that two of Soora’s sisters were married even before she was born; reveal the dark reality of women’s lives in those times. The young girl also constantly faces taunts about being an unwanted child, and while the mother reassures her of that being a falsehood, a sense of being traumatised by the possibility of that fact continues to linger over Soora’s life. Yet, as the memoir unfolds, one senses that Soora’s life is still a privileged one where owing to her class position, she is surrounded by simple comforts of a home where along with her basic needs being well taken care of, her ability to attend school is facilitated by the presence of helps who accompany her to school – a luxury many of Soora’s friends are not entitled to, resulting in their dropping out of school and getting married at a very young age.

But the intersectionality of issues that impinge gender issues is well brought out when one discovers that the advantages of class offer no protection from the various kinds of repression that Soora is made to face on account of her religion. Even after she gets admitted into a prestigious school at Kozhikode, uncertainty looms large over Soora’s life as her mother stays adamant about not allowing her daughter to wear a skirt as a uniform as mandated by the school. There is also always the constant presence of violence, or the threat of violence that this young girl is made to confront, seemingly innocuous but leaving a lasting impact.

Writing without a room

So is this a good memoir? Should one read it? Well, the answer to this question is a little long-winded but it is an emphatic yes. When we look at writing by women, we need to look at it beyond its aesthetic merits as literature. The very act of writing is an act of resistance for women living in a patriarchal society that creates many hurdles that stand in their way of getting an education, their having a room of their own, or a time that they could demand as their own to devote to writing. Also, a memoir such as The Dreams of a Mappila Girl goes beyond giving us a glimpse into one young girl’s life, and offers us an intimate view of a society, a community, and the lives of women who lived in these suffocating conditions, mostly capitulating to their circumstances but sometimes daring to chart a new way of life.

Finally, a word about the translation by Fehmida Zakeer, which is so well done that the memoir reads really smoothly. That is no mean task for a memoir which not only evokes a way of life that maybe culturally unfamiliar to many, but is also situated in a past whose ways are difficult for us to always make sense of.

Shibani Phukan teaches English at a Delhi University college.

Featured image: Deepak H Nath / Unsplash

source: http://www.livewire.thewire.in / Live Wire / Home> Books / by Shibani Phukan / September 01st, 2022