Its red sandstone boundary walls are defaced with posters and betel juice marks. Shopkeepers hang cases full of clothes and jewellery on them. Inside the walls the dry fountains gather dust and filth. This is the state of the maosoleum of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, independent India’s first education minister, whose 125th birth anniversary will be observed Monday.

Situated in the heart of the bustling Meena Bazar, the garden-tomb of India’s prominent independence leader and close associate of Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister, the mausoleum is surrounded by numerous shops selling food, mobiles, CDs, clothes and other knick-knacks. Open sewers and a dump yard nearby tell a tale of unbelievable civic and governmental neglect.

Apart from the apathy of the authorities in maintaining the site, what stands out is that even most residents are not even aware about the mausoleum of a leader who is credited with establishing a national education system and modern institutes of higher education, including the Indian Institutes of Technology. His birth anniversary is also observed as National Education Day.

Walking down the winding by-lanes in search of the mausoleum, one is startled to learn that most of the locals are oblivious of his name, leave alone the location of the memorial. It’s indeed ironic how the man who persuaded thousands of Muslims during partition to stay back in India is now a forgotten man.

The boundary walls of his mausoleum have become billboards for local politicians, quacks and restaurants, while the temporary stalls adjacent to these walls have further damaged it by hammering nails and creating deep holes in places.

The gate has a lock, but it might as well not have one.

As you enter the small black iron-gate, a short staircase leads to a garden where people, mostly shopkeepers, are having lunch or a siesta. It is perhaps the only place offering peace and tranquillity in the midst of a maddening market and has thus become the resting place for many. That is another reason why the mausoleum is at least still maintained, though empty packets and wrappers of eatables and plastic bottles are scattered around the boundary walls.

In one corner is the mausoleum made of white marble with a patch of green grass on top. A canopy and a short boundary wall, both made of white marble, cover it from rain and sun – and more importantly, bird droppings. The fountains and pools, on the front and on the sides of the mausoleum, are empty and full of dust and filth, while the garden has patches of grass. Lichen covers the trunks of many trees.

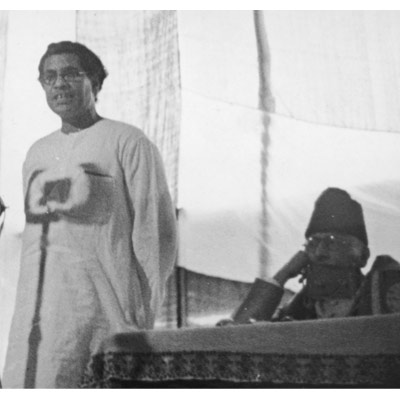

The famous Urdu Park in front of the mausoleum, where Azad along with Sardar Patel, independent India’s first home minister and now much in the news, and C. Rajagopalachari, India’s first governor-general, delivered the historic 1942 Quit India address, is a playground for amateur cricketers during daytime and a haven for drug addicts and drunkards at night.

Sadly, it seems no one cares. For the locals, the mausoleum was just what it was – a mausoleum. “I know it’s a mazar (mausoleum) but I don’t know whose it is,” Abdul, a shopkeeper selling blankets near the boundary wall of the memorial, told IANS.

Similarly, tourists who come in droves to visit the nearby Jama Masjid and Meena Bazar, famous for affordable women’s apparel and accessories, give the memorial a miss as they are oblivious of its existence and importance.

Azad’s grandnephew Firoz Bakht Ahmed is not surprised at the neglect. “Since independence, he (Azad) never got the importance that he deserved. The government as well as the people have forgotten him. It’s a tragedy,” Ahmed told IANS. He said leaders like Azad, Patel and many more deserved much more recognition and respect. “There should be chapters in schools where students are taught about them and not just a handful of freedom fighters,” he said.

Talking about the poor maintenance of the memorial, Ahmed said that squatters should be removed from near the site and proper security arrangements put in place. “He was a freedom fighter and a nationalist leader known for his secular thoughts and was one of the few Muslim leaders who strongly opposed the partition of India. But sadly, he is not remembered now,” he added.

source: http://www.dnaindia.com / D NA / Home> India> Report / Agency: IANS / Sunday – November 10th, 2013