Awadh, UTTAR PRADESH / Kolkata, WEST BENGAL :

Following up on The New York Times article on the imposters who called themselves the descendants of Wajid Ali Shah, we trace the last prince of Awadh and the story of a family that settled in Kolkata after decades on the move.

________________________

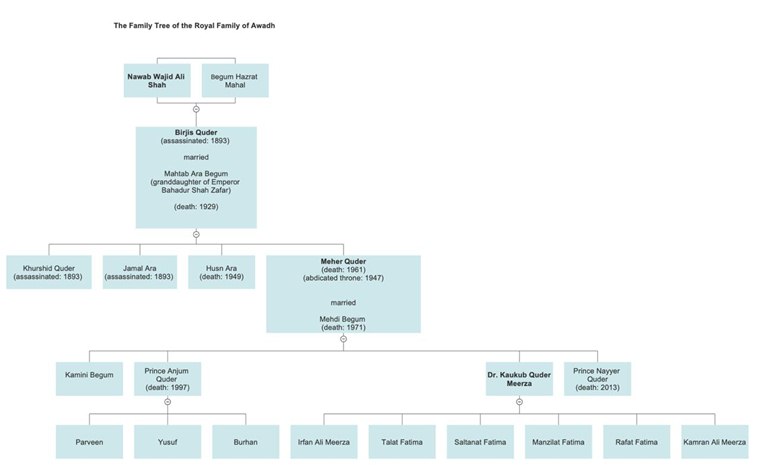

Dr Kaukab Quder Meerza, 86, doesn’t keep well these days. Long conversations are challenging for him and his children and grandchildren have to help him walk short distances inside the house. His home, deep inside a bylane in the heart of Kolkata, an old, unassuming, one-storey building, is easy to miss if one isn’t paying attention. The modest interiors of his residence give no indication of who Meerza is or his family’s legacy. They are the last remaining descendants from the ruling line of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, the last ruler of the kingdom of Awadh in India.

In November, The New York Times article titled “The Jungle Prince of Delhi ‘, brought focus back on the descendants of the Nawab after the story revealed that a family living in the ruins of a 14th-century hunting lodge in New Delhi for decades, claiming to be the descendants of the Awadh rulers, were actually imposters.

An ‘absurd’ story

Meerza and his family in Kolkata are familiar with the story of Wilayat Mahal, as are most people who have been associated with the former princely state of Awadh in various capacities or have spent time researching on Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. Wilayat, the woman at the centre of the deception, along with her son Ali Raza, also known as Cyrus, and her daughter Sakina, entertained journalists, mostly those from overseas, with her claims of ancestry, and the journalists, in turn, dedicated hours of time and spools of newsprint in telling their dramatic story.

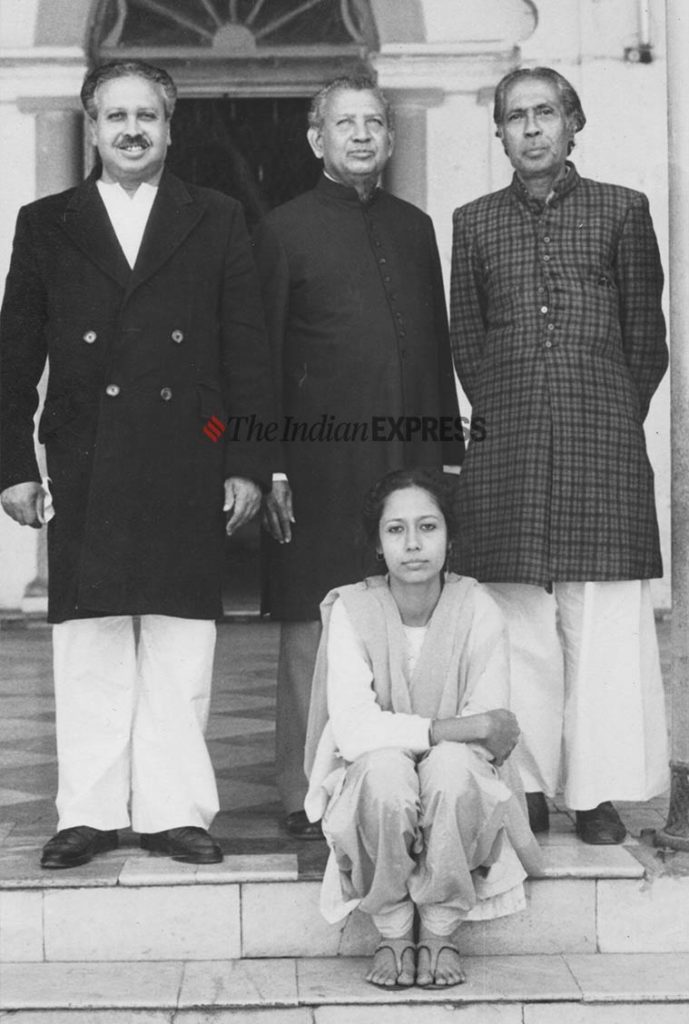

“It was absurd,” says Meerza, recalling his meeting with Wilayat Mahal in the 1970s-80s. When Wilayat made her first appearance at the New Delhi railway station, Meerza and his brothers Anjum Quder and Nayyer Quder agreed that it was necessary to meet her to learn more about the basis of her claims. The family decided that Meerza would travel to Delhi for that purpose, having studied the family history most extensively. He doesn’t remember his first meeting with her very well—some four decades have passed since—but the second visit is more vivid in his memory.

_________________________

Sometime after his first meeting with Wilayat, Meerza took another trip to Delhi and met her at the Maurya Hotel, now called ITC Maurya. “She said many things about herself,” recalls Meerza. “With great difficulty, she met me because the place (the room they met in) was reserved for VIPs. The lady talked about nothing in particular.” It isn’t immediately clear why it was a challenge to meet Wilayat because Meerza’s age and health have impacted his speech.

A few of Meerza’s children and grandchildren who still live in Kolkata are gathered around him and his younger daughter Manzilat Fatima, 52, and son Kamran Ali Meerza, 46, express surprise at the revelation. Although Wilayat’s story is familiar to the family, this is the first time they have heard about their father’s second meeting with her. As he begins his tale, his voice becomes louder, emphatically denouncing the stories Wilayat and her children had spun over the years.

“It was a dark place and the meeting was absurd,” Meerza continues. Wilayat wore a sharara, he recalls, just like women did centuries ago in Lucknow, in the royal courts, not a sari, perhaps to add more credence to the character she had been attempting to play. “She wasn’t wearing jewellery. It was absurd. She spoke to us in Urdu and sometimes in English.” During their conversation, not once did Wilayat disagree that Meerza’s family members were descendants of Wajid Ali Shah. “We were interested in knowing the background of the lady. Of course, we told her about us. She never denied that we were from Wajid Ali Shah’s family, but she presented herself as a representative of the family. I told her that she was not a representative and that she was talking (about) absurd things.”

Meerza remembers that Wilayat showed some newspaper cuttings, not legal documents, to lend credibility to her claims. “Whenever I said anything about the branch of Birjis Quder’s family, she never (responded). I said that whatever she was talking about the background of the family was absurd. That she was not talking correctly about the family.” In this meeting, Meerza says, there was no sign of Wilayat’s daughter Sakina. “Only her son was there. A little older than Kamran now,” says Meerza, gesturing towards his son. “I’m sorry that I met her.”

_________________________

After The New York Times story was published, Manzilat told her father that the world now knew what the family had been trying to tell people about Wilayat Mahal for decades. “What is there to say about that?” asks Meerza about the story. To Meerza and his family, and to many others who met Wilayat over the years, the revelation came as no surprise.

The Nawab’s 300 wives

“There is a saying that if you throw a stone in Lucknow, it will fall on a Nawab’s kothi (house). All fake. Most of them are fake,” says Manzilat. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was a documented hedonist, who found joy and solace in music, women and extravagance and had some 300 wives, many of whom he divorced when the period of his decline started, presumably in an attempt to lessen his financial burden and responsibility. It is difficult to state the exact number of his descendants, but the figure would be somewhat in proportion to the number of Wajid Ali Shah’s consorts, in addition to his official spouses and the children he had with them.

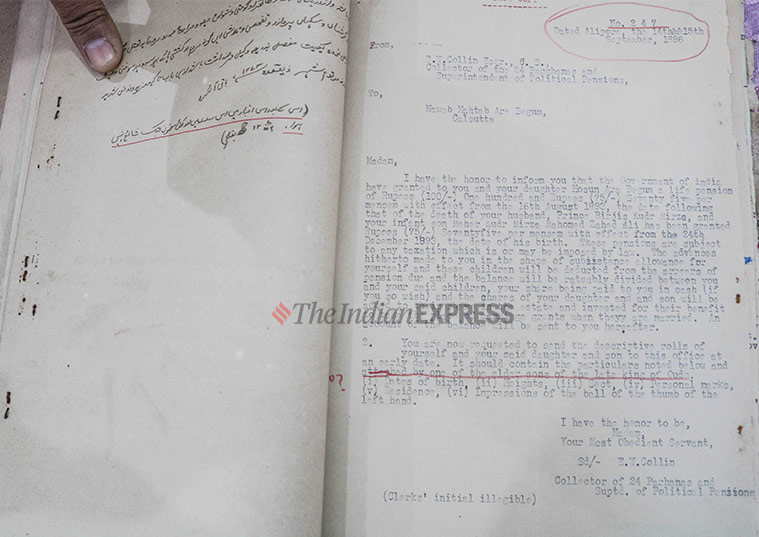

The British officials who deposed and drove Wajid Ali Shah out of Awadh and imprisoned him in Calcutta in 1857, recorded the names of 185 officially recognised wives of the Nawab and his children. This list was published in the Awadh Pension Book of 1897 after the death of Wajid Ali Shah’s son and successor, Birjis Quder, the last official ruler of Awadh.

___________________________

The descendants mentioned in the Awadh Pension Book of 1897 were allotted political pensions, first given by the British government in India, a responsibility that later transferred to the government of independent India in 1947. The central government made no alterations to the names of the descendants mentioned in the Awadh Pension Book of 1897 and has continued paying the required monthly pension ever since. The Awadh Pension Book, however, hasn’t prevented pretenders in Lucknow and elsewhere from sprouting, claiming ancestry to the family, because few bother to check official documents to verify such claims.

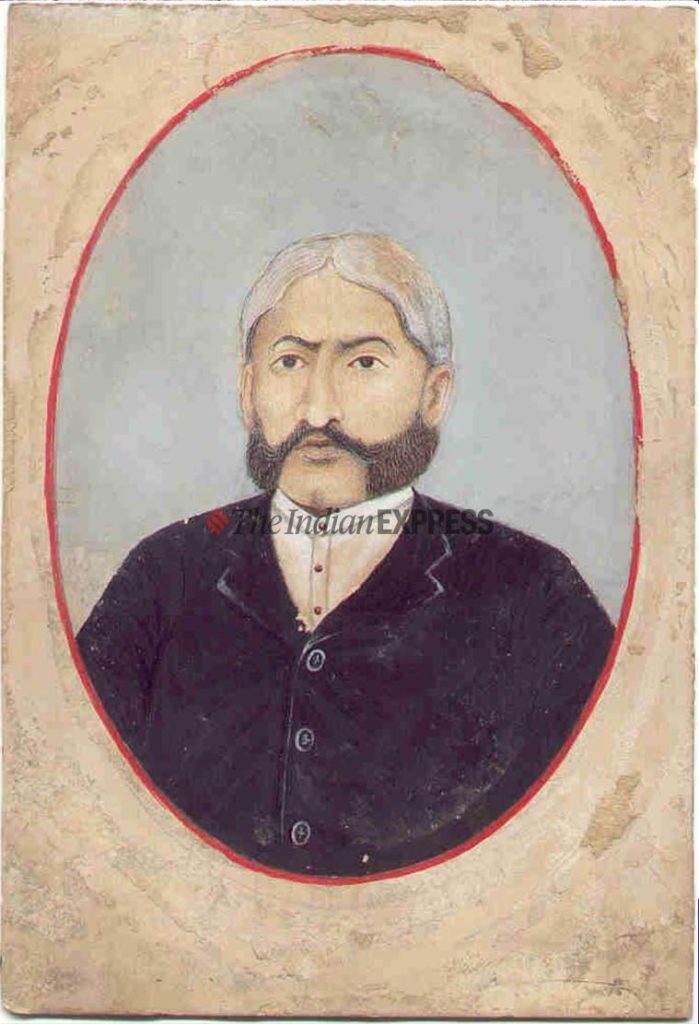

Meerza’s family are direct descendants of Birjis Quder, the son of Wajid Ali Shah and his wife Begum Hazrat Mahal, a courtesan who became the second official wife of the Nawab. But it would be doing Hazrat Mahal a disservice if she were to be dismissed as a mere court dancer whose fortunes changed when she captured the Nawab’s fascination and favour.

________________________

“She was a warrior and she was a purdah nasheen,” says Manzilat of her ancestor, who lived wearing a customary veil that she removed to launch into war with the British. When Wajid Ali Shah was dismissed and dispatched from Awadh, Begum Hazrat Mahal actively engaged in opposing the British during the Rebellion of 1857 on her own accord, without having been given any special political appointments by the deposed Nawab.

Her resistance against the British proved to be futile and she was compelled to flee Awadh. Taking her son Birjis Quder, she sought asylum in Nepal under the protection of King Jung Bahadur Kunwar Rana who demanded hefty financial compensation in return. The mother and son spent close to two decades in Nepal, but not much is known about their circumstances or where they found the finances to live in the country. Hazrat Mahal died away from her homeland, in a nameless grave in Kathmandu, forgotten till only recently.

The last Nawab of Awadh

Sometime in 1893, according to her father’s research, says Manzilat, Birjis Quder, now the ruler of Awadh in exile, was coaxed by the other wives and children of Wajid Ali Shah who had followed the Nawab to Calcutta, to join them in the city. “It was a conspiracy,” says Meerza, a statement he repeats several times during the interview with indianexpress.com. “It was a conspiracy among the other families of Wajid Ali Shah and the British because Birjis Quder was the last legal heir. The conspiracy was hatched and he was invited by deceit. They told him that he was the head of the family now and Birjis Quder was taken in by the sweet talk. So of all the places, he came to Calcutta. He could have also gone to Lucknow,” says Manzilat.

______________________

According to the story passed down in the family, Birjis Quder and his eldest sons Khurshid Quder and Jamal Ara were invited for dinner by the other families of Wajid Ali Shah on the night of August 14, 1893. All three died the next day, having been poisoned. When news reached of their murders, Birjis Quder’s wife, Mahtab Ara Begum, who was the granddaughter of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal Emperor of India, fled Metiabruz, the neighbourhood in Calcutta where they had been staying, while she was pregnant with Mehr Quder, along with her remaining daughter, Husn Ara and reached central Calcutta in search of a safe house.

“When news of the death arrived, she ran from Metiabruz, along with her precious potli of jewels. These things I don’t know (much about), but my father will know,” says Manzilat. The house where the family now live in is not only unique because of its residents, but the building itself is of little-known historical importance.

“Perhaps she didn’t buy this house that very night itself. But she put up in another place somewhere close by in some small room, while she was trying to find some protection. From that time onwards, we are here and it’s my father’s wish that as long as he is around, we cannot construct anything here,” says Manzilat, looking around the living room of their home. Mahtab Ara Begum’s son Mehr Quder had three sons and one daughter, including Manzilat’s father Kaukab Quder Meerza.

___________________

“The last pension holder is Dr. Kaukab Quder Meerza, the last living member of that generation,” says Sudipta Mitra, author of the book ‘Pearl by the River: Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s Kingdom in Exile’, who has conducted research on the Nawab for more than a decade. The various provisions of this pension mean that Meerza is the last remaining recipient of this monthly pension that will not be transferred to Manzilat or her five siblings, Irfan Ali Meerza, Talat Fatima, Saltanat Fatima, Rafat Fatima and Kamran Ali Meerza. Prince Anjum Quder died in 1997, years after the death of his daughter Parveen. His two sons, Yusuf and Burhan live elsewhere in the country with their families and don’t spend much time in Kolkata these days. Prince Nayyer Quder never married. Unlike his brothers, Kaukab Quder Meerza never used the title of ‘Prince’ before his name, preferring to use the title of ‘Doctor’ to signify the Ph.D that he earned, explains Manzilat.

Mitra says this list and its provisions, left by the British, documenting the descendants of Wajid Ali Shah, not only provide a monthly pension to listed descendants, but it also serves to provide recognition to the descendants because it is the most authentic documentation available of the Awadh royal family tree. It also helps weed out pretenders like Wilayat Mahal and her children, who find no mention in either the Awadh Pension Book of 1897 or in other historical documentation and research on Awadh.

Asked about Wilayat Mahal, Mitra dismisses her entirely. “I did not find their names in the records and was hence not interested in them. They did it for publicity,” says Mitra.

Fake nawabs of Lucknow

The controversy surrounding claimants who say they are descendants of the Nawab or of the larger Awadh royal family is nothing new, but according to Mitra, there is very clear historical documentation that helps sift out fraudulent claims for those bothering to do the research. “When Wajid Ali Shah lived in Lucknow, there were many taluqdars who lived like kings themselves. So their descendants call themselves ‘royal’,” says Mitra of some such claimants. Mitra believes that although the Awadh Pension Book of 1897 is not the full and final record of all of the Nawab’s wives and children, it is the most authentic record available.

______________________

So why then did the Uttar Pradesh government or the Indian government not do anything to weed out the imposters? “The belief is that the imposters are harmless. They aren’t taking anything. They aren’t asking for anything,” says Manzilat. She points to some individuals who live in Lucknow and have made the make-believe their business where they attempt to cash in by claiming to recreate the Awadh of the Nawabs and Awadhi cuisine, purportedly representing food as it was cooked in royal kitchens, especially for foreign tourists. “It is difficult to deny Dr. Kaukab Quder Meerza’s ancestry,” says Mitra. “The government has recognised the family and that is why they get the pension.”

There is little doubt that Wilayat Mahal and her family were a nuisance for the Indian government. She was attracting crowds and journalists and was occupying the VIP room at the railway station, filled with her children, fripperies, dogs and carpets. During their second meeting at the Maurya Hotel in Delhi, Meerza remembers that there were talks going on between the Indian government and Wilayat that were perhaps not heading in the direction in which she would have liked. Although the government eventually gave Wilayat consent to live with her children and dogs in Malcha Mahal, the dilapidated 14th century hunting lodge in the middle of Delhi, Meerza says in no way should it be considered official recognition of her claims.

“She did not get any recognition from the government. Forcibly living in the (railway) station was not the right thing (to do),” says Meerza. Two years ago, after the death of Wilayat’s son Cyrus, when he was able to speak more clearly, Meerza told his family that the Indian government gave Malcha Mahal to Wilayat not to give recognition to them, but because they were creating nuisance in public. “In order to keep them quiet, the government gave them ruins and she accepted it. No royal would accept something like this,” says Manzilat. “She was also offered some flats in Lucknow but she refused to accept it.”

Battling historical inaccuracy

The family continues to battle misinformation about their ancestors, particularly Wajid Ali Shah, especially concerning the time the Nawab spent in Calcutta. Government apathy towards correcting historically inaccurate information frustrates the family, but they say there is little they can do. Nobody has conducted as much research on Nawab Wajid Ali Shah and his wife Begum Hazrat Mahal, the line from which the Kolkata family descend, as Dr Kaukab Quder Meerza, but few are listening.

A few years ago, says Manzilat, heritage walking tours in the city held in conjunction with the city government began claiming that the Bengal Nagpur Railway (BNR) House in Kolkata, a large mansion in the Garden Reach neighbourhood of the city, was where Wajid Ali Shah once stayed in during his time in the city. A plaque was also installed in the premises of the mansion stating that this fact had been verified by her father. Local newspapers and blogs began repeating those claims and the myth took a life of its own, including a mention on Wikipedia. “My father’s name has been used to claim that the BNR property was a place where Wajid Ali Shah stayed. But my father is the sole authority (on the family history), and there is no evidence that (the BNR building) was associated with Wajid Ali Shah,” says Manzilat.

After graduating from St. Xavier’s College in Kolkata with a Bachelors in Economics, Meerza went on to do a double Masters in Political Science and Urdu from Aligarh Muslim University. When he started a Ph.D at Aligarh, his advisor told him to consider conducting research on his own family’s history, on Wajid Ali Shah. The family believes the thesis written in Urdu is the most comprehensive documentation of Wajid Ali Shah and his wife Begum Hazrat Mahal, and Manzilat’s elder sister Talat Fatima, 62, is in the process of translating it to English.

Helping Satyajit Ray write ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’

In October 1976, when Satyajit Ray began writing his screenplay for the film ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’, set in the backdrop of Awadh during the First War of Independence of 1857, the filmmaker made a trip to the Imambara Sibtainabad in Calcutta to learn more about the subject. Wajid Ali Shah’s descendants in Kolkata are trustees of the Imambara and Anjum Qudr directed Ray to his younger brother Meerza, who was at that time teaching Urdu as a lecturer at Aligarh Muslim University and simultaneously researching on Nawabi Lucknow and specifically, Wajid Ali Shah.

_____________________

That was how Satyajit Ray came to engage with Meerza in a long-term correspondence through letters, to better understand the character of Wajid Ali Shah for his screenplay. Over the course of weeks, Ray and Meerza discussed less well-known aspects of the Nawab’s life and Nawabi Lucknow, and conducted in-person meetings where the director made trips to Aligarh where Meerza had been occupied with his teaching and research.

“In my screenplay, I show (Wajid Ali Shah) as a tragic figure who realises that he should not have sat on the throne but should have pursued an artistic career. Do you agree with this viewpoint?” asks Ray in one of his first few letters to Meerza. The purpose of the correspondence, Ray says in his letter, was to fill in gaps of information that the filmmaker had found in his own research on Wajid Ali Shah.

Meerza doesn’t bring up his correspondence with Ray during the interview. His son Kamran shares this information, remembering at least one visit that the filmmaker made to their Kolkata home when Kamran was still a young boy, and opens up a folder containing letters exchanged between his father and the filmmaker. ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’ would have probably still been made even if Ray had never corresponded with Meerza, but would it have been the masterpiece that it is without Meerza’s contributions? It is difficult to speculate but perhaps for this very reason, Ray invested time and funds pursuing Meerza’s insight and knowledge of his ancestor, and travelled around the country while Meerza was dividing his time between Kolkata and Aligarh.

_____________________

Last remaining royal artefacts

The family doesn’t have many belongings of historical significance, in part due to the circumstances in which their ancestors fled for their lives. But two royal seals, carefully wrapped in a large square piece of red velvet fabric, are exceptions. One is a small rectangular metal seal with etchings of daggers and an inscription in Urdu that reads: ‘Nawab Hazrat Mahal Sahiba’. The etchings on Hazrat Mahal’s seal are unique because they feature daggers instead of floral motifs, signifying her role as a warrior queen who defended her kingdom against the foreign invasion of the British, explains Manzilat.

The second seal is slightly larger, featuring the royal coat of arms of Awadh, with elaborate etchings of floral motifs and an inscription in Arabic and Urdu. The calligraphy is elaborate and the family struggles to translate it; they’ve never done it before. Due to his age, Meerza finds it difficult to read the finely etched calligraphy of the seal. The family turns to Kamran’s wife Nuzhat Zahra, a 36-year-old lecturer in Urdu and a research scholar in the city, for help. Her Urdu language skills are better than those of her husband and his siblings.

______________________

Not much is known about the circumstances that Birjis Quder found himself in, in a foreign land, far away from his home and inheritance, or even his thoughts at watching the British loot and strip his father of everything that he ever had. But perhaps the sentiments of the last Nawab of Awadh can be found in the elaborate calligraphy of the inscription denoting an Arabic phrase, followed by his royal titles, alqaab, on his seal:

“NarsuminnAllah Fatun Qareeb”; Help from Allah and a near victory.

“Sikander Iqbal Shah, Khudullah Mulkohu Mirza Birjis Quder Mohammad Ramzan Ali”; His Highness keeper of Allah’s heaven-like nation. Mirza Birjis Quder Mohammad Ramzan Ali.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / Indian Express / Home> Research / by Neha Banka / Kolkata – January 04th, 2020