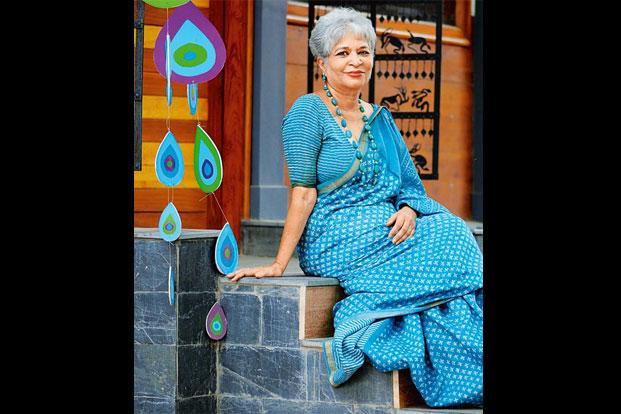

For 30 years, the face of Dastkar has worked with craftspeople, documenting their art and preparing them for an urban clientele

Freedom to use skills | Laila Tyabji In 1949, a two-year-old girl came to Bombay from Belgium, where her father had served as India’s first ambassador. She was pale-skinned, cute, funny and only spoke French. “I was such a joke in India,” recalls Laila Tyabji. She promised herself that she would never be laughed at again, lost her French and became the Indian child she was. Tyabji was born a few months before the metaphorical midnight into a Sulaimani Bohra Muslim family of Delhi in 1947.

In 2012, Tyabji was honoured with the Padma Shri Award for her long and inspiring contribution to India’s crafts sector as a co-founder, and now the chairperson, of Dastkar—a society for crafts and craftspeople. Her only regret receiving it was that it was given by Pratibha Patil, who Tyabji felt was an inappropriate choice as president. “Especially as the attempt was to tell us that her appointment was a triumph for women,” she adds.

Clarity of thought and commitment to larger goals in life distinguish her from the six purposeful women who founded Dastkar in 1981. The other five founding members moved on with goals of their own, while Tyabji stayed on and became the face of Dastkar and its Nature Bazaars held all over India. Despite a large, well-delegated team, people only want to speak to Tyabji when they call the office. Even if it is just to ask for directions to Kisan Haat, now the permanent venue for the bazaars in Delhi. Tyabji spent years trying to get a permanent venue.

As a young student at the Welham Girls’ School in Dehradun who would later study art in Vadodara and go on to work with Japanese artist Toshi Yoshida in Tokyo, her perseverance has never deserted her. Spirited and outspoken, Tyabji rode motorcycles in the 1970s before feminism gained momentum in India. Tyabji remembers feminist activist Kamla Bhasin telling her many years ago that it was because she painted her toenails that she saw her as a social butterfly. That was till Bhasin saw her working assiduously in the villages of Bihar and yet fitting in perfectly in south Delhi’s drawing rooms.

In the late 1970s, Tyabji got a three-month assignment from the Gujarat State Handloom & Handicrafts Development Corporation Ltd’s Gurjari outlet, to go to Kutch as a visiting designer. Her belongings in a steel trunk, she drove through villages, documenting the work of craftspeople, finding things for Gurjari, preparing them for an urban clientele. “Three months became six. I would sit with the women to do the embroideries and the patchwork. The only way to teach is with personal intervention, that’s how you can hone skill,” she says.

Kutch became the hotbed of work and inspiration for her, its crafts evoking a lifelong quest; its craftspeople, her friends and protégés. “Beyond her image as a sophisticated and stylish woman, Laila could make and hold a bridge with craftspeople. She has been there for them through calamity and crisis; from teaching them how to price their products to valuing themselves. The respect and affection they have for her is rare,” says Archana Shah, founder of the chain of Bandhej stores and author of Shifting Sands, Kutch: Textiles, Traditions, Transformations, launched by Tyabji in New Delhi earlier this year.

___________________________________________________________________________

“I would sit with the women to do the embroideries and the patchwork. The only way to teach is with personal intervention, that’s how you can hone skill.”

___________________________________________________________________________

After returning from Kutch, Tyabji, whose personal style then was about motorbike helmets and textiles, worked as a buyer and merchandiser for Taj Khazana, the store known for finely curated Indian arts and crafts, at New Delhi’s Taj Hotel on Man Singh Road. “A small logistics issue about the Assam state emporium not being able to supply handmade cane baskets to the city-based Taj Khazana propelled the Dastkar idea. That rural craftspeople needed new and commercially viable markets and a bridge to meet their customers and sell directly to them,” she says. The first Dastkar crafts bazaar was held at the Triveni Kala Sangam in New Delhi in 1981.

Mapping the personal and creative direction for craftspeople, forming a link between them and their city buyers, and doggedly working on design issues, pricing, sizing and policy changes for the evolution of the crafts sector as a business model could sum up Tyabji’s work at Dastkar. “They are skilled professionals and should not be treated as downtrodden or as relics as they often are,” insists Tyabji, who has also been associated with Sewa (the Self Employed Women’s Association) of Lucknow. Designer Aneeth Arora of péro, who has been following Tyabji’s work for the last 10 years, says this assimilation of crafts and textiles at Nature Bazaars helps her tremendously as a designer keen on textile exploration and use. The bazaars, feels Arora, are research centres to understand innovation and locate weavers to work with from different regions.

Tyabji’s path, though, is not always well-paved. Craftspeople are deeply conservative, averse to experimentation, nervous about newness. They don’t understand fast colours, form or financial management, she explains. “When you begin you are cocky and romantic, but craftspeople can also start misbehaving. Sometimes you put in so much work but what comes out is a mouse.”

That’s why she has always been a hands-on mentor. Till Tyabji turned 50 and decided to cut her hair short and only wear saris, thus creating the lasting image we have of her, she only wore clothes she had hand-stitched and hand-embroidered. In her closet hangs a fine collection of pherans, anarkalis and a variety of long kurtas with Lambani, Kutchi and Chikankari embroidery done by Tyabji—each piece stunning.

She still paints her toenails. And still hand-embroiders in her free time. She stopped wearing a watch 25 years ago, when she realized that being chronically punctual while working in rural India, where time was a flexible concept, was stressful. She is more nonchalantly stylish than ever before. Short, salted hair, handloom saris, Kolhapuri chappals, kohl-lined eyes, jewellery that is distinctive but never too craftsy, Tyabji cuts a tall figure on India’s “most stylish” lists.

“Laila is knowledge-oriented, decisive and endlessly patient without using her personal influence to change the tide of things,” says Shelly Jain, personnel and programme head at Dastkar and Tyabji’s colleague of 17 years. Her home mirrors her; it is modern Indian without ethnic monstrosities for artefacts. And as its mistress, the only daughter among four siblings, she cooks, bakes, knits and sews enviably.

She admits she came close to getting married a few times but “shrank back” because she was never sure how she would feel 15 years down the line. She shrugs in her characteristic way even as her god-daughter Urvashi Kumari Singh comes up to hug her amma. “She is a fair, cool and sometimes irritable mom,” says Singh.

Is there a retirement age when the trajectory of Dastkar and its chairperson might move in different directions? “I have been trying to retire for the last five years, but haven’t been successful so far,” says Tyabji. That’s when a little emotion wells up—who on earth wants her to retire anyway.

“You can’t imagine Dastkar without Laila,” as Jain says.

source: http://www.livemint.com / Live Mint & The Wall Street Journal / Home> Lounge> Business of Life> Indulge / Home – Leisure / by Shefalee Vasudev / Saturday – Augut 09th, 2014