Wasiq Khan, the production designer of ‘Goliyon Ki Rasleela Ram-Leela’, on creating magic and realism

It was Dhankor’s first scene in the movie, and a debate was raging about the curtains.

Should they be ornate like the apparel and jewellery in which the fearsome matriarch of the Saneda clan in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Goliyon Ki Rasleela Ram-Leela is swathed, or should they provide a dash of simplicity?

There were close to 200 samples from which to choose. Production designer Wasiq Khan asked an assistant to put up a roughly textured jute curtain on the wall. Bhansali loved it. The curtain stayed in the scene.

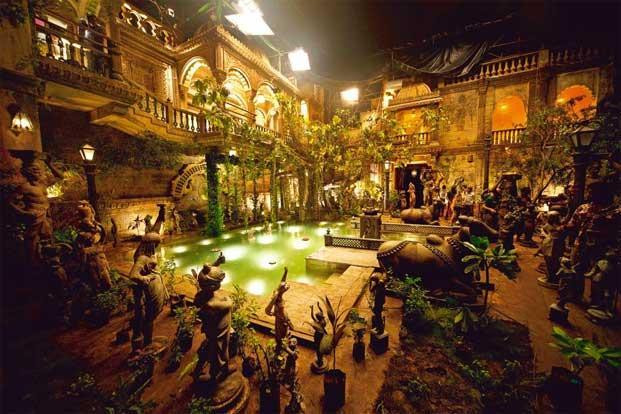

Bhansali’s superbly choreographed treatment of William Shakespeare’s Romeo And Juliet is also his lightest work till date. Here, as in his previous productions, are the epic sets that create a cosmos of impossible beauty, the decorative touches for ordinary objects, the perfectly coiffured men and women. But here is also a grungy underside to the flourishes, playful backdrops, and the co-existence of grandeur and rusticity. Bhansali’s choice of Khan, who has for years created the illusion of reality in modestly budgeted productions, has resulted in a gypsy opera that is more tethered to verisimilitude than previous ventures like Devdas, Black, Saawariya and Guzaarish

Ram-Leela might be a mild departure for Bhansali but it has set Khan firmly on the road to bigger things. An acolyte of renowned production designer Samir Chanda, Khan has worked closely with film-maker Anurag Khashyap as well as designed such films as Dabangg, Rowdy Rathore andBesharam. He is among the people who create Hindi cinema’s newfound love for lived-in texture, and the go-to man for a level of detailing that seems utterly natural despite being utterly manufactured.

“My school is the Samir Chanda school, which is more realistic and rustic,” Khan says. “In the old days, production designers were called art directors but many of them were glorified carpenters. All rooms had that painting of Arjun and Krishna from the Mahabharat and two sunmica tables. The villain’s den had to have a stuffed tiger. Nobody bothered talking to the art director about costumes.” Greater attention is being paid to costumes, sets and locations than ever before, he says. “Audiences do care for realism, and you can’t take them for granted any more.”

Khan cut his teeth on such Kashyap films as Black Friday, set in the middle-class neighbourhoods and slums of Mumbai, That Girl in Yellow Boots, which unfolds in the city’s grungy parts, and Gangs of Wasseypur, shot at over 300 locations in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. “I did my first commercial film because there was gadbad (trouble) in my kitchen,” he says. “Even when I did Dabangg, I maintained a sepia tint and a rustic feel. But on a film like Ram-Leela, you can open your mind and imagine things, let the artist inside you wake up even as you try to maintain the realism.”

Bhansali came calling because of Rowdy Rathore, which the filmmaker co-produced. He wanted to keep the Baroque style for which he is known but also wanted to create a parallel universe that would be believable, Khan says.

The merry mix of magic and realism is what makes Ram-Leela so special. Everything is decorated, from tattooed bodies to encrusted guns and bandhini-patterned cellphone covers. There are nods to Baz Luhrmann’s anachronisms and V. Shantaram’s invocation of temple art and architecture. The porn movie parlour run by Ram, the movie’s Romeo, is designer seedy, with neon-lit cut-outs and lurid poster art. In the weapon- storage room, guns peek out of straw baskets and from inside shimmering back-lit glass cases as though they were diamonds. The love story’s Juliet, Leela, exchanges naughty SMSes with Ram in a chamber that has Raja Ravi Varma paintings and diaphanous curtains. Glasswork patches liven up rough-hued walls, not unlike homes in the Kutch region whose craft traditions and folk culture have influenced Ram-Leela’s design and narrative.

“We worked primarily with two colours, black and burgundy, and tried to give a rustic feel in every set,” Khan says. (Bhansali didn’t respond to interview requests.)

The extended and expensive production schedule—over 200 days—was very different from what Khan is used to. He is something of a heartland specialist in his ability to conjure up a “gareeb (poor)” aesthetic, as he says. “Whenever people don’t have budgets but want to make their films look good, they think of me.”

Khan learnt his craft from the man whom he calls Dada. Chanda, who died in 2011, followed in the tradition of celebrated realism specialists Bansi Chandragupta, Satyajit Ray’s long-time collaborator, and Sudhendu Roy, the leading art director for Hindi films from the 1960s to the 1990s. Chanda recommended Khan to Kashyap for Last Train to Mahakali, his contribution to the fictional drama series, Star Bestsellers, that aired on Star TV in 1999. “Dada introduced me to Anurag as his best product, and told him that he should take me away and not send me back,” says Khan.

He had meagre resources to work with on Last Train to Mahakali, as well as for Kashyap’s unreleased debut feature,Paanch, made in 2003. The resourcefulness born out of need combined with the belief, drilled into him by Chanda, that sets would be convincing only when they looked lived in. “There are sets and then there are sets that indicate that somebody has lived there,” Khan says. “A place must have soul and feeling.”

Khan has been integral to Kashyap’s noir-influenced cinema right from the beginning. “We didn’t have a lot of money for Paanch, but we wanted to make the scenes look rich,” Kashyap says about his debut, in which members of a music band commit murder to fund their dreams. “There is a red room in Paanch that was Wasiq’s brainchild,” Kashyap adds. “I told him about my hostel room, with graffiti on the wall. He said, give me the graffiti and I will figure out how to do it, and he did. His ability to transform something from ordinary to extraordinary and make it look real and never lose character is why we work together.”

However, the two did not collaborate on Dev.D or Kashyap’s forthcoming Bombay Velvet. “We didn’t work on Dev.Dbecause both of us were in different zones, but we missed him a lot,” Kashyap says. “He is tremendous at turning minimal into maximum.”

Khan studied at the faculty of fine arts at the Jamia Millia Islamia university in Delhi. His family was far removed from the tinsel trade, and Khan was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and become an engineer. He met Chanda while he was a student, on the sets of Ketan Mehta’s Sardar. He got chatting with Chanda, who handed him a business card.

After his graduation in 1996, Khan arrived in Mumbai with Chanda’s business card in his pocket. He dialled the landline number listed on the card, only to discover that the line had been disconnected. He worked his Jamia contacts and got a job at the Kamalistan studio, painting backdrops for art director Ratnakar Phadke. Khan finally met Chanda a few months later, who recruited him as an assistant for Mani Ratnam’s period Tamil film Iruvar. Over the years, Chanda became a surrogate parent for Khan. “He was like my father, we would talk every few days,” Khan says.

He also picked up from Chanda the ability to improvise at short notice. When a shoot for Rahul Dholakia’s political drama Lamhaa in 2010 had to be shifted abruptly from Kashmir to Mumbai because of security concerns, Khan created a set with “truckloads of chinar leaves” that were brought in from the state. “People started calling me from Kashmir and asked me where we had shot the sequence—when you create realism, people do notice.

Chanda’s advice remains a lodestar for the 38-year-old production designer. “I still try and maintain the rules and standards Dada gave me,” he says. “He told me to never stop thinking that the job is done. I don’t do too many films—he used to tell me that money tends to come all of a sudden.” Yet, Khan has been unable to resist the demand for his services. He is now working on the Bhoothnath sequel, a biopic on the political prisoner Sarabjit Singh, a remake of the Tamil film Ramana, and 21 Topon ki Salaami, about P.N. Joshi, a put-upon government employee whose sons try to honour him with a 21-gun salute at his funeral.

Joshi’s chawl abode is a good example of Khan’s adeptness at mimicking reality. Packed into the tiny space are a stainless steel vessel rack, a goddess-themed calendar, a mezzanine storage loft and the ice-cream spoon holder with fake purple flowers that is a common sight in middle-class homes. “You can’t pinpoint it when you watch a movie, but you can feel it,” Khan says about the art of creating the invisible, yet visible, backdrop. “Everything should not be perfect, since life isn’t perfect.”

source: http://www.livemint.com / Live Mint / Home> Leisure / by Nandini Ramnath / Saturday – November 20th, 2013