JHARKHAND / NEW DELHI :

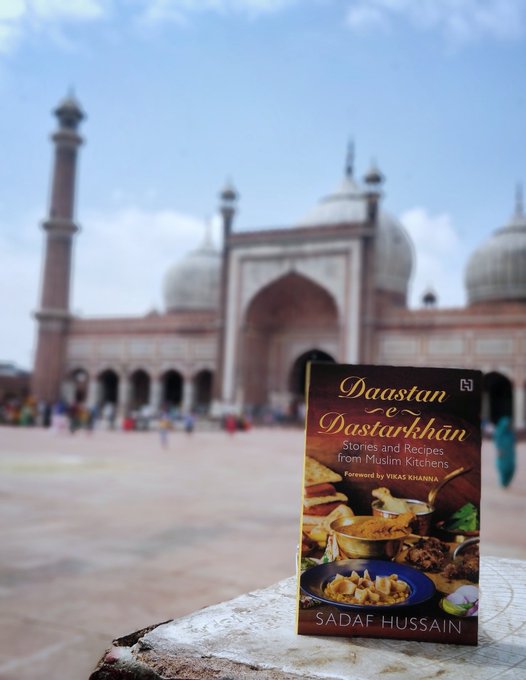

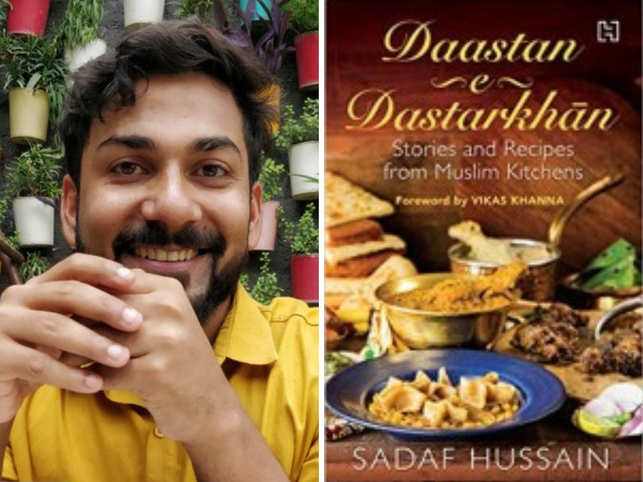

Sadaf Hussain chronicles home-made food in his new book Daastane-Dastarkhan.

Sadaf Hussain’s charming new, first book Daastane-Dastarkhan has been published by Hachette India.

Sadaf Hussain’s charming new book Daastane-Dastarkhan starts with the story of a pir who, every Thursday, visited his mother’s family in Sasaram, Bihar. But one day he appeared on a Wednesday, throwing his grandmother into panic because there was no meat for the aloo-gosht she always fed him. She had to be inventive. She used dried figs and poppy seed paste, to make a salan, threw in fried potatoes, balanced it with garam masala and chillies, and served it with rice and besan rotis. The pir was delighted: “May Allah bless you with an abundance of food and may no one ever leave your home hungry.

A recipe like this is not what many would think of as Indian Muslim food. Where is the intense meat focus? Where are the kebabs and biryanis? The problem starts with thinking there is something that can be neatly labelled Indian Muslim food. The fact that people do this might be just another way in which Indian Muslims are diminished by clubbing their many communities into one and ascribing easy stereotypes to them.

Part of the problem is that there is a market in catering to such stereotypes. Once a year during Ramzan, many people decide to have an iftar experience and go out — without fasting — to eat the rich food cooked on street sides for the occasion. But this has as little relation to regular home food in Muslim communities across India, as does a Diwali or Christmas feast have for Hindu or Christian home food.

One way people get exposed to home food of different communities is when they share food with neighbours, especially as kids. But as housing becomes increasingly segregated, this is becoming harder.

This lack of knowledge has been compounded by a curious lack of cookbooks from different Indian Muslim communities.

There are cookbooks from cities like Lucknow and Hyderabad where certain types of Muslim food dominate, but what’s presented tends to be street food or special occasion dishes, both mostly made by men. These are important, but it means that the daily, home dishes get left out.

There have been a few exceptions. Ummi Abdulla made a pioneering contribution by documenting the food of the Malabar Muslim, or Moplah, community, with all its complex interactions between the local ingredients of Kerala and influences from Arab traders.

Bilkees Latif ’s Essential Andhra Cookbook captured similar interactions from Hyderabad. Mumbai’s Inquilab newspaper brought out a collection of booklets, in Urdu and English, on Memon, Kokani, Bohra and Kashmiri food. There were a few other books printed privately or abroad, but little else.

Adil Ahmad’s Tehzeeb chronicles the home food of an upper-class Lucknow family.

Doreen Hassan’s Saffron and Pearls does the same for her husband’s family from Hyderabad, but with roots in both Persia and Uttar Pradesh. Zaiqa e-Kadwai provides a very different perspective. It is a team effort to document the food of a village in Ratnagiri district, where most of the families just happen to be Muslim, but their food is quite typically Konkani. Hazeena Syed’s Ravathur Recipes: With a Pinch of Love shows, in a very impressively produced volume, the food of this Tamil Muslim community.

These books show the food of these communities to be, as with all communities in a region, primarily dictated by what’s locally available, but with small tweaks. As Hassan’s husband’s family shows, at a more upper-class level there were more likely to be interactions with communities across countries, and recipes travel with daughters-inlaw, who are one of the least acknowledged agents for social change.

There is certainly a lot of meat eaten in all these communities, but the recipes are much simpler and subtler than what is served up to unthinking eaters as “Muslim” food. Meat is often cooked with vegetables as in the chuqandar gosht, beetroot and mutton; or keema kakdi, cucumbers and mince, given in Tehzeeb. There are inventive egg dishes, like boiled eggs stuffed with mince and then skewered, that Hassan discovers in Hyderabed, or eggs fried in gravy that are a favourite in Kadwai.

Other similarities might be slightly more use of some spices, like star anise, and less of others — hing rarely features since onions are widely used. Chefs will tell you that Muslims in their kitchens are particularly adept at frying, and that copper, with its excellent heat conduction, is the metal of choice for utensils. Many traditional vessels shown in these books are copper, and careful distinctions are made in types of frying: shallow, deep, braising and so on.

Books like these are important because, apart from the problems of unthinking stereotypes, the food of Indian Muslim communities faces another kind of obliterating pressure. Many cooks from the communities have gone to work in the Gulf and have picked up the kind of Lebanese-Arab food that is becoming a standard across the world. It is easy to produce, cheap and tasty enough and has the allure of being modern, rather than old-fashioned, labour-intensive home food. People shouldn’t be faulted for opting for what’s cheap and convenient, but it is important to remember, as these books remind us, that there are also other ways to nourish our roots.

source: http://www.economictimes.indiatimes.com / The Economic Times / Home> Business News> Magazines> Panache / by Vikram Doctor / ET Bureau / October 13th, 2019