Panipat, HARYANA / Mumbai, MAHARASHTRA :

On the occasion of writer-filmmaker Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s 102nd birth anniversary that fell earlier this week, some reflections on his first movie Dharti Ke Lal, a film that was not available for public viewing until about a year back…

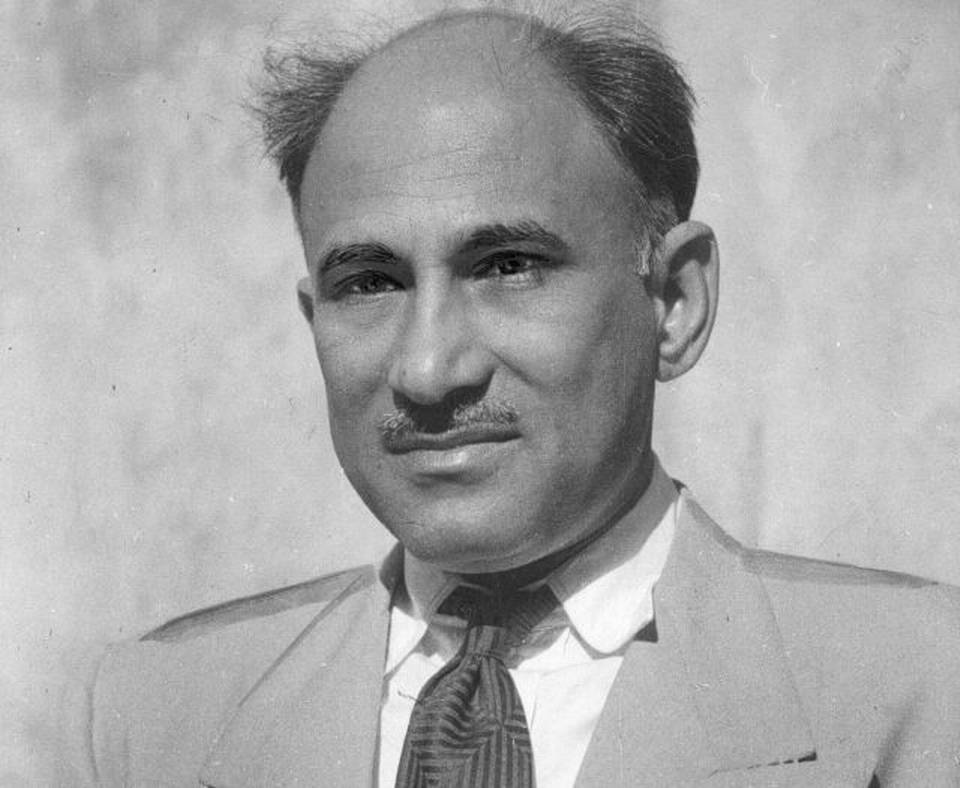

The name Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, whose 102nd birth anniversary passed by this week with nary a mention of him in mainstream media, rings a bell in the mind of an average cinephile primarily for two reasons. The first is as the story/screenplay writer for Raj Kapoor’s cinema; and the second is as the filmmaker who introduced the star of the millennium, Amitabh Bachchan, to Hindi films. His directorial output, comprising 14 feature films and numerous short films and documentaries, is either ignored or overlooked.

This year is special for someone who wants to get introduced to Abbas’s cinema — heavily influenced by the art of Soviet filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin — as it marks seven decades since his first film, Dharti Ke Lal (Sons of the Soil) was released. It was a unique experiment by the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), co-founded by Abbas, at film-making and an early example of Indian film industry’s tryst with social realism. This was the realism of the kind that would be seen later in the films of Satyajit Ray, Bimal Roy and Mrinal Sen.

The tale of a peasant family’s struggles during the British-authored Bengal famine of 1943 during World War-II, the film was a combined adaptation of three literary works — Bijon Bhattacharya’s Bengali play Nabanna; a Hindustani play Antim Abhilasha; and Krishan Chander’s short story Annadata.

Dharti Ke Lal can also be considered a part of an Abbas trilogy (emphasis mine) of 1946. The three films — the other two being Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani and Neecha Nagar, both written by him — presented three different ways in which he expressed the idealism of a common man in pre-Independence India. Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani, a biopic on Dr. Dwarkanath Kotnis, was based on Abbas’s story, And One Did Not Come Back. It showed a young doctor, inspired by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s call to serve the wounded Chinese during the Sino-Japanese War, staking his career to serve the dispossessed masses in a distant country. This was a primer into Abbas’s early-day internationalism.

Neecha Nagar by Chetan Anand, about a nonviolent rebellion by residents from a decrepit shantytown, shows an educated youngster Balraj (Rafiq Tanwar) motivating and organising the masses to speak up against Sarkar (Rafi Peer), the municipality head. Abbas’s desire to lift the urban subaltern to a state of peaceful revolution found expression through the screenplay of the movie.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VLv5Nb4M534&feature=player_embedded

Neecha Nagar – Part 1 of 10 – Cannes Awarded Indian Classical Movie

source: http://www.youtube.com

Dharti Ke Lal, with a young peasant Niranjan (played by Balraj Sahni) in the lead role, was much more explicit than Neecha Nagar in advocating for independence and self-rule. It is set in Ameenpur, a village in pre-Partition Bengal, is slowly coming to grips with India’s struggle for independence. Through references to Saare Jahan Se Achcha, with Ravi Shankar’s music playing in the background, Abbas introduces a nationalist tenor into the film.

The first half, where the family of Samaddar, the village pradhan (head) and his son, Niranjan, tries to live a happy, agrarian life within their means, is an early-day attempt at realistically portraying the village life. This is celluloid portrayal of the kind of society people got introduced to through Munshi Premchand’s novels like Godan and short stories like Panch Parameshwar. Tropes like the affinity of the villagers toward their land and the affection they show toward their cattle and cow are straight out of a Premchand short story.

The second half, where Samaddar’s family is forced to migrate to Calcutta is Abbas’s attempt to see the city through the prism of a humble peasant. The scarcity created by the famine; the apathy of the rich in the city; and the simmering Hindu-Muslim animosity combine to create absolute misery in the lives of the economic migrants. They further encounter indifference as they are forced to beg. Finally, following the end of famine, they are forced to return to their village where they mobilise themselves into a group and practise saajhe ki kheti (collective farming).

Coming back to the Abbas trilogy part, while Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahaani and Neecha Nagar were inspired by Nehru’s vision of an enlightened urban India, Dharti Ke Lal seeks to emphasise Gandhian ethos of seeking comfort in the village life.

In terms of aesthetic merits, Dharti Ke Lal ranks equal to the likes of Do Bigha Zameen made in the next decade. The affection with which the camera views the villagers as it takes their close-ups makes the characters and their situations relatable. Just notice the sense of wonder on the faces of the family members in the 10th minute as they welcome the clouds, emphasising the love-hate relationship a farmer enjoys with the monsoons. The poignancy of the moment is accentuated by an alaap, with a flute playing in the background. This surely reminded me of joy in the face of villagers of Champaren in Lagaan as they anticipate the rains on seeing the clouds, expressed through the ghanan-ghanan song.

source: http://www.youtube.com

In a radio interview quoted in an audio tribute, Abbas expressed a sense of pride when he says that Dharti Ke Lal is the only film that was ‘socialist’ when it comes to the production process. He says none of the members was paid less than Rs.200 or more than Rs.400. His socialist ideals and life-long belief in upliftment of the downtrodden — his commitment to idealism made journalist Vinod Mehta compare him to historian Eric Hobsbawm — kept informing his writing and his film-making.

source: http://www.youtube.com

His production company, named ‘Naya Sansaar’ (A New World) was his way of voicing his message of empowerment as he made films like Shahar Aur Sapna, Do Boond Paani and Saat Hindustani. Most of them were commercial disasters and some of them look didactic from a 2016 viewpoint. However, if there is one film that has remained relevant, both in terms of its art and its content, it is Dharti Ke Lal.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Cinema / by Hari Narayan / June 11th, 2016