Agra, UTTAR PRADESH :

Anyone travelling on India’s road network in the north of the country may from time to time see a curious little structure standing in isolation by the side of the road. Seemingly unassociated with anything else around them, to the casual observer they can probably be best described as enlarged stone salt/pepper pots.

With all the astonishing monuments that still stand today in this amazing country, it would be all too easy to dismiss these humble little constructions as your car passes them by at speed. However, they have their own story to tell, and one for which we can draw so many parallels with life as we live it today in terms of travel and communication. They are also a type of monument that is slowly disappearing from the landscape of India, so they deserve a little time in the spotlight before it’s too late.

These monuments are known as Kos Minars. A Kos is an ancient Indian unit of distance representing approximately 3.22 kilometers (2 miles), and is 1/4 of a Yojana, a vedic measurement of distance. The use of Yojana scratches back to the ancient vedic texts, and was used by Ashoka in his Major Rock Edict No.13 to describe the distance between Patliputra and Babylone. Minar means ‘Pillar’, so the broad translation of Kos Minar is ‘Mile Pillar’, even though one kos is not strictly speaking an exact mile in measurement. Interestingly, elderly people in many rural areas of the Indian subcontinent still refer to distances from nearby areas in kos.

A Short History of the Kos Minar

The first recorded evidence in India of using something in the landscape to specifically denote distances and routes comes from the 3rd century BC. The Emperor Ashoka established routes linking his capital city of Pataliputra to Dhaka, Kabul, and Balkh, and landmarks in the form of mud pillars, trees and wells helped guide the travelers and provide a sense of how far they had traveled and how much further they had to go. In the majority of cases these landmarks were already pre-existing in the landscape, they were not created specifically for this purpose.

In India the notion of purposely building structures to physically denote distances in the landscape was first adopted by the Mughal Emperor Babur during his short reign from 1526 to 1530. He ordered one of his central asian nobles, Chiqmaq Beg, to measure the road between his new capital Agra and Kabul in modern day Afghanistan, with the assistance of a royal clerk. He then ordered the raising of distance markers, each twelve yards high and topped with a superstructure having four openings, at every nine kos all along the measured route.

It is not clear how far the builders got with Babur’s instructions, but we do know that the Pashtun ruler Sher Shah Suri who ruled from 1540 to 1555 greatly expanded on this earlier plan. He paid great attention to the development of the road network in northern India, recognising them as arteries to the empire, and erected Kos Minars along the royal routes from Agra to Ajmer, Agra to Lahore, and Agra to Mandu. These three major routes, which were called Sadak-e-Azam, became later known as the Grand Trunk Road.

(File is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0. Source.

Many of the Kos Minars you can see today can probably be attributed to the time of Akbar, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Abul Fazl recorded in Akbar Nama (the official chronicle of the reign of Akbar) that in the year 1575 Akbar issued an order that, at every kos on the way from Agra to Ajmer, a pillar or a minar should be erected for the comfort of the travelers, so that the travelers who had lost their way might have a mark and a place to rest. Between 1615 and 1618, shortly after Akbar’s reign, early European travelers to India brought back detailed reports of the Kos Minars they had seen, most notably Richard Steel, John Crowther, and the ambassador of King James I, Sir Thomas Roe.

Subsequent Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan added to the network of Kos Minars, by now they were an institution. In 1619, Jahangir ordered Baqir Khan, the garrison commander of Multan, to erect Kos Minars from Agra to Lahore. Thirty four of these milestones still exist today in Punjab in varying states of preservation. It is estimated that between 600 and 1,000 minars were erected in total during the Mughal period, but of course today only a fraction of that number still exist.

Construction and Function

Kos Minars are round pillars around 30 feet high built on a masonry platform. They are completely solid with no stairs or internal rooms, and are mostly made of brick and once covered with lime plaster.

Whilst the features of a Kos Minar generally match each other they are not all identical, there are slight differences depending on location and time of construction/repair.

Many of the Kos Minars you can see today stand in isolation, but that was not always the case. As the network of pillars expanded, so did associated structures to complement them and assist the traveler. Scholars believe there were three categories of Kos Minar along the major routes.

- The first category is just a standalone Kos Minar with no supplementary infrastructure, erected purely for landmark identification.

- The second category of Kos Minar had small associated contemporary buildings, offering limited facilities for the travelers.

- The third category of Kos Minar had substantial additional infrastructure such as sarais (inns), baolis (wells), mosques and other facilities to ensure the safety, security and well-being of the traveler. There is some speculation that Chor Minar in Delhi is one such example, although the passage of time may have blurred that fact and introduced folklore into the narrative for that monument. Throughout most of the world you can see this infrastructure in operation along the major roads of any given country. In the UK we call them “service stations”, which exist at fairly regular intervals along our extensive motorway network.

These structures not only served to assist the traveler from place to place, but were also instrumental in the day to day governance of the Mughal empire. Horses, riders and drummers were stationed at many of the Kos Minars, relaying royal messages at a much faster speed than would be possible with a single horse and rider from source to destination.

In addition to helping relay messages from place to place, Kos Minars may have also served as a hub of information themselves. Some scholars believe the plastered surface of the Minar would have been covered with information, not just about distances but also recent news and popular slogans. This method of distributing news, information and propaganda throughout an empire was not a new concept. The Roman emperor Caesar introduced a similar model where information he wanted to share with his people was posted daily on wooden boards in the Forum (center) of major cities in the Roman empire.

Today we have technology to help us communicate these things. You can post messages on someone’s “wall”, or provide information to a Facebook group (often geographically centric). For many people, social media began with the advent of Facebook, but this is a modern term that refers to a very old idea that people have been using for thousands of years.

Distribution and Preservation

The passage of time has not been kind to the Kos Minar. Of the approximately 1,000 that once existed in India there are now just 110 examples still standing, the highest concentration is in the state of Haryana, where 49 are to be found.

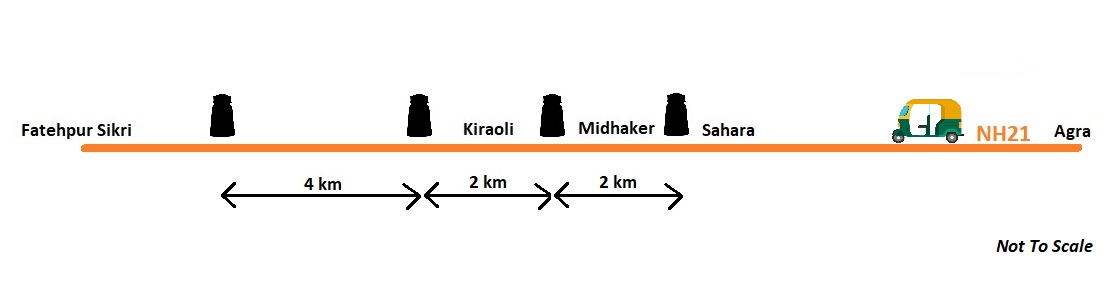

For those who are perhaps traveling to northern India to see the major tourist sites, there is a good stretch of them surviving by the side of NH21 between Agra and Fatehpur Sikri. Hopefully the map below will prove useful for that purpose (click on the image to view larger scale):

Heading away from Agra towards Fatehpur Sikri look out for the following four Kos Minars on the right-hand side of the road :

- Kos Minar #1 : Just after the village of Sahara. This Kos Minar (ASI ref: N-UP-A33) is visible and marked on google maps, co-ordinates 27.154760, 77.886290.

- Kos Minar #2 : This one (ASI ref: N-UP-A34) is 2 km further on just after the village of Midhaker, and is also visible on Google Maps but not marked, co-ordinates 27.151050, 77.860133.

- Kos Minar #3 : (ASI ref: N-UP-A35) is 2 km further on towards Fatehpur Sikri after the village of Kiraoli.

- Kos Minar #4 : The final one (ASI ref: N-UP-A36) is after a longer gap of 4 km (clearly we have lost one in middle of these last two).

Although all Kos Minars are now declared protected monuments by the ASI, they remain structures at great risk. What were once meant to show the way to others often now stand in near obscurity, isolated in zoos (Delhi), jungle, car parks, villages, slums, farmlands and even beside railway tracks. Others are being devoured by the rising skyline of rapid development in urban areas, being swallowed up and becoming almost invisible.

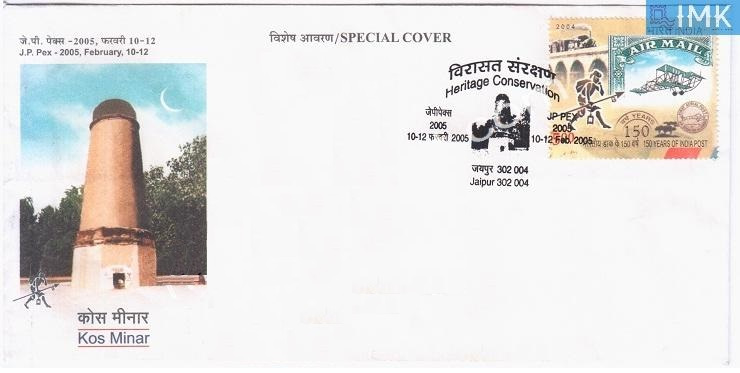

Attempts have been made to increase awareness, most recently in February 2005 when a first day cover was issued depicting a renovated Kos Minar as a symbol for Heritage Conservation.

I hope efforts continue to raise awareness of the Kos Minar, and hopefully ensure they no longer lose their way in the rapidly changing landscape on India.

Please ‘Like’ or add a comment if you enjoyed this blog post. If you’d like to be notified of any new content, just sign up by clicking the ‘Follow’ button.

If you’re interested in using any of my photography or articles please get in touch. I’m also available for any freelance work worldwide, my duffel bag is always packed ready to go…

KevinStandage1@gmail.com

source: http://www.kevinstandagephotography.wordpress.com / Kevin Standage / Home> Agra / by Kevin Standage Photography / May 20th, 2019