Unveiling a tale that is sure to tease your taste buds, we trace the gastronomic journey of Mughal cuisine in India from Babur to Aurangzeb.

One of the most powerful dynasties of the medieval world, the Mughals are entwined inseparably with India’s history and culture. From art and culture to architecture, they bequeathed to this country a substantial legacy that lives on even today.

But what often gets forgotten is that they also left us a rich culinary legacy — the deliciously complex blend of flavours, spices, and aromas called Mughlai cuisine.

Tracing the origins of this cuisine in India, we unveil a tale that is sure to tease your taste buds!

photosource: https://www.facebook.com/motimahaldeluxknl/

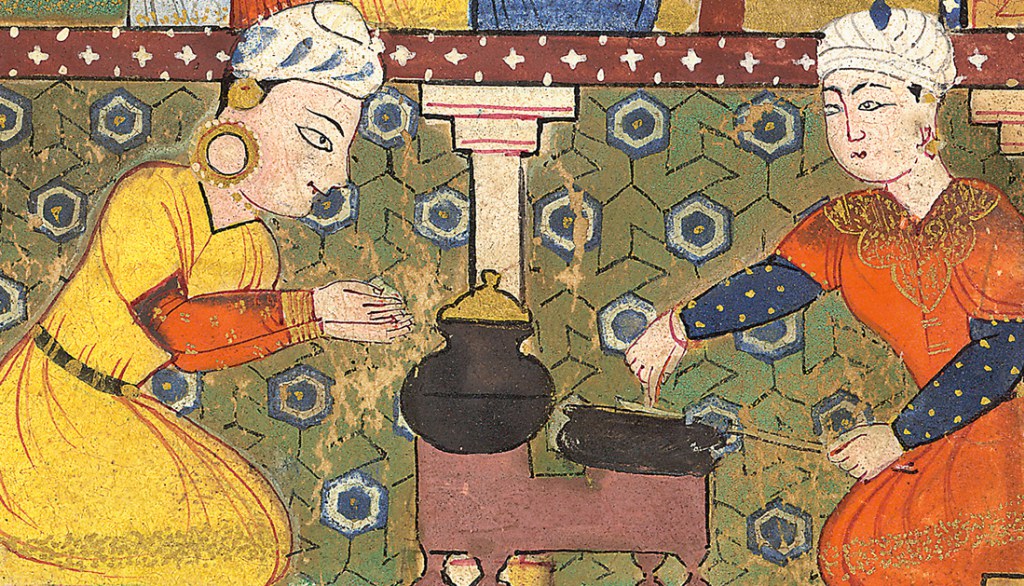

Lavish and extravagant in taste, the Mughals were connoisseurs of rich, complex and sumptuous recipes. Creating such dishes meant that cooking in royal kitchens was a riot of colours, fragrances, and harried experiments.

Curries and gravies were often made richer with milk, cream and yoghurt, with dishes being garnished with edible flowers and foils of precious metals like gold and silver.

It was also not uncommon for the shahi khansama (chief cook) to consult with the shahi hakim (chief physician) while planning the royal menu, making sure to include medicinally beneficial ingredients. For instance, each grain of rice for the biryani was coated with silver-flecked oil (this was believed to aid digestion and act as an aphrodisiac).

Flavour-wise, the royal cuisine of the Mughals was an amalgamation of all kinds of culinary traditions: Uzbek, Persian, Afghani, Kashmiri, Punjabi and a touch of the Deccan. Interestingly, Shah Jahan’s recipe book Nuskhah-yi Shah Jahani reveals much about the intermingling of these traditions in the imperial kitchens, including a fascinating account of the then-world’s largest sugar lump!

photosource: https://alifatelier.wordpress.com/category/mughal-miniature-painting/

As for the contributions of the Mughal emperors themselves, each of them added his own chapter.

The foundation, of course, was laid by Babur — the dynastic founder who brought to India not just an army, but immense nostalgia for a childhood spent in the craggy mountains of Uzbekistan.

Not a fan of Indian food, he prefered the cuisine of his native Samarkand, especially the fruits. A legend has it that the the first Mughal emperor would often be moved to tears by the sweet flavour of melons, a painful reminder of the home he’d lost. Interestingly though, he loved fish – which he did not get back in Uzbekistan!

Historical accounts also reveal the prevalence of cooking in earth ovens — earthen pots full of rice, spices and whatever meats were available would be buried in hot pits, before being eventually dug up and served to the warriors. As this suggests, Babur’s cooks were primarily attuned to war campaign diets and employed simple grilling techniques that utilised Indian ingredients.

On the other hand, Humayun — an emperor who spent much of his life in exile — brought Persian influences to the Mughal table. More accurately, it was his Iranian wife Hamida who introduced the lavish use of saffron and dry fruits in the royal kitchens during the first half of the 16th century.

photosource: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tahmasp_I#/media/File:Tahmasp,_Humayun_Meeting.jpg

Humayun was also immensely fond of sherbet. So beverages in the royal household began being flavoured with fruits. As such, ice was brought from the mountains to keep the drinks cool and palatable.

However, it was during Akbar’s reign that Mughlai cuisine truly began evolving. Thanks to his many marital alliances, his cooks came from all corners of India and fused their cooking styles with Persian flavours.

The result? Some of the most unique, elaborate and delicious meals in Mughlai food.

Take, for instance, the magnificent Murgh Musallam, a whole, masala-marinated chicken stuffed with a spice-infused mixture of minced meat and boiled eggs before being slow-cooked.

Or Navratan Korma (curry of nine gems), a deceptively delicious dish prepared from nine different vegetables coated in a subtly sweet cashew-and-cream sauce.

Interestingly, Akbar was a vegetarian three times a week and even cultivated his own kitchen garden — the emperor ensured that his plants were carefully nourished with rosewater so that the vegetables would smell fragrant on being cooked!

Akbar’s wife, Jodha Bai, is also believed to have introduced panchmel dal (also called panchratna dal) into the predominantly non-vegetarian Mughal kitchen, along with a handful of other vegetarian dishes. It became such a big hit with Mughal royalty that by the time Shah Jahan took over the throne, the court had its own shahi panchmel dal recipe!

Mughlai cuisine continued to evolve swiftly during Jehangir’s reign. The reins of the empire lay with his twentieth wife, Mehr-un-Nisa (better known as Nur Jahan). An enormously powerful figure at the royal court, the empress would often be gifted unique preparations by visiting traders from European nations such as France, Britain and Netherlands.

A true aesthete by nature, Nur Jahan used these ideas to create her legendary wines, rainbow-coloured yoghurt and dishes decorated with pretty patterns of rice powder glaze and candied fruit peels!

photosource: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nur_Jahan

However, it was during the reign of Jehangir’s son that the Mughal cuisine reached its zenith. The greatest of the Mughals in pomp and show, Shah Jahan’s first step was to enlarge the menu devised by his father and grandfather.

He instructed his cooks to add more of spices like haldi, jeera and dhania to royal recipes for their medicinal properties. Interestingly, a legend has it that his cooks also added red chilli powder to keep evil spirits at bay!

Another legend explains the origins of the nihari, a spicy meat stew that is slow-cooked overnight in large cauldrons called shab deg. This is how the story goes:

In the 17th century, soon after Shah Jahan established his capital in Delhi, a virulent flu swept through the sprawling city. It was then that the shahi khansama and the shahi hakim joined their hands to devise a robust spice-packed stew that would keep the body warm and fortified!

Interesting, another popular story traces the origins of biryani to Mumtaz Mahal, Shah Jahan’s beautiful queen who inspired the Taj Mahal.

photosource : https://www.thebetterindia.com/60553/history-biryani-india/

It is said that Mumtaz once visited the army barracks and found the Mughal soldiers looking weak and undernourished. She asked the chef to prepare a special dish that combined meat and rice to provide balanced nutrition to the soldiers – and the result was the biryani of course!

Also Read: The Story of Biryani: How This Exotic Dish Came, Saw and Conquered India!

The extravagance of Mughlai cuisine during Shah Jahan’s reign was toned down by his son Aurangzeb.

The most religious and frugal of all the Mughal emperors, Aurangzeb fancied vegetarian dishes like the aforementioned panchmel dal more than the roast meat dishes that found favour with his uncles and brothers.

According to Rukat-e-Alamgiri (a book with letters from Aurangzeb to his son), Qubooli — an elaborate biryani made with rice, basil, Bengal gram, dried apricot, almond and curd — also held a place of pride on the dining table of Aurangzeb.

It was also during Aurangzeb’s reign the intermingling of Mughal and Deccan culinary traditions gained momentum (the kitchen moved with the emperor when he went on wars). During this time, Agra and Delhi started to lose their preeminence as hubs of Mughal culture, with the focus shifting to cities like Hyderabad and Lucknow.

Take, for instance, haleem, present-day Hyderabad’s favourite Ramzan street food which also has a prized Geographical Indication (GI) tag.

photosource : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9caUDHNk0Qg

A deliciously thick paste of meat, wheat, spices and ghee, haleem‘s first recorded appearance in India was in the 16th century according to the historical text Ain-i-Akbari.

Written by Abul Fazl, the book also mentions that there was a Minister of Kitchen during the reign of Akbar.

While the dish’s exact origins are difficult to pinpoint, haleem is believed to have made its gastronomical journey to the Deccan during the Mughal era.

In the years to come, the secrets of the imperial kitchens gradually made their way across the country — not just to the royal kitchens of princely states but also to the gullies and bazaars of many Indian towns.

photosource: http://www.icytales.com/gourmet-history-biriyani/

And over the centuries, they made their way to fancy restaurants, old-school outlets and home delivery services in bustling cosmopolitan cities.

So the next time you dial for Mughlai paratha and Reshmi Tikka, spend a minute thinking about (and perhaps, thanking) all those food-loving emperors, their fashionable wives and their hardworking khansamas!

Interestingly, the tale of Mughal culinary culture is incomplete without a mention of the dynasty’s fondness for mangoes!

A sole exception to this rule, Babur had little time for mangoes. However, such was Humayun’s love for the fruit that he took care to ensure a good supply of mangoes (through a well-established courier system) while on the run from India to Kabul.

photosource: https://veryshortnews.com/mango-facts/

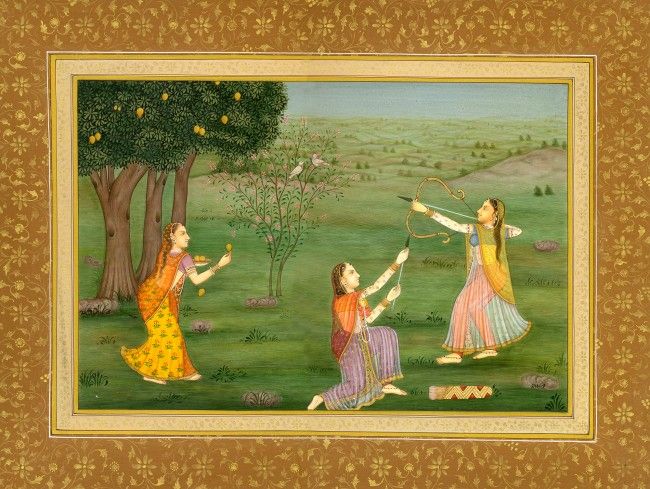

Akbar built the vast Lakhi Bagh near Darbhanga, growing over a hundred thousand mango trees. This was one of the earliest examples of the grafting of mangoes, including the Totapuri, the Rataul and the expensive Kesar.

Shah Jahan’s fondness for mangoes was so deep that he had his own son, Aurangzeb, punished and placed under house arrest because the latter kept all the mangoes in the palace for himself!

In fact, Jehangir and Shah Jahan even awarded their khansamas for their unique creations like Aam Panna, Aam ka Lauz and Aam Ka Meetha Pulao (a delicate mango dessert sold all through the summer in Shahjahanabad). It was also mangoes that Aurangzeb sent to Shah Abbas of Persia to support him in his fight for the throne!

(Edited By Vinayak Hegde)

source: http://www.thebetterindia.com / The Better India / Home> Food> History> India / by Sanchari Pal / August 31st, 2018