JAMMU & KASHMIR :

A Review of Dr. Nazir Ahmad Zargar’s Recent Book

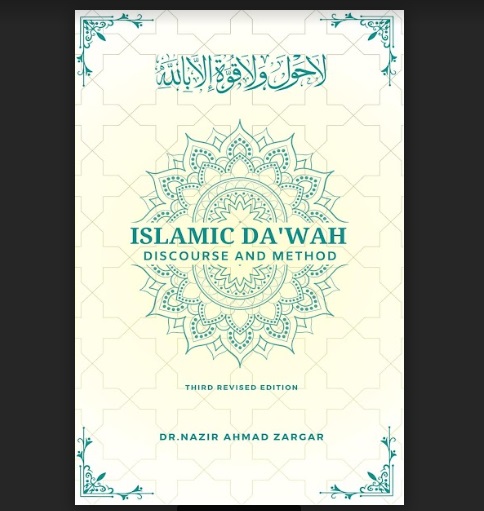

Author: Dr. Nazir Ahmad Zargar, Title: Islamic Da‘wah Discourse and Method, Publication Details: Chahattisgarh: Evincepub Publishing, 2024., Edition: Third Revised Edition , Pages: 297+ i-xx. ISBN: 978-93-5673-906-2. Price: ₹500

Islam is a missionary religion, and Da‘wah (the call to Islam) is a divine commandment. In common terms, Da‘wah invites people to Islam. A person who invites people to Islam through a dialogue process is called Dā‘ī. In a broader sense, it connotes an invitation to the Imān (Islamic faith) to the prayer or Islamic way of life. The book under review attempts to elucidate the methodological aspect of Da‘wah in the contemporary era.

The author maintains an academic tone throughout the book and presents Islamic Da‘wah as a means to eliminate misrepresentation, misinformation, and misconceptions regarding Islam and its worldview. Therefore, the main objective of this work is to make its readers understand that Da‘wah is an attitude that presents the actual teachings of Islam and the real image of Islam, free from division and prejudice. The methodological aspect of this work highlights the role of a Dā‘ī in contemporary times. In this context, the book offers a comprehensive approach to Da‘wah. The author deals with the communication part of Da‘wah methodology, including using social media and modern technologies to propagate the message of Islam.

The revised third edition has been improved to a greater extent than early editions; some sections have been edited with great detail. A few portions have been added afresh. The foreword of the revised third edition is written by Prof. S. M. Yunus Gilani, Malaysia. He says, “This work is an invaluable resource for anyone seeking to understand the essence of Islam, its profound teachings, and the wisdom behind its principles. It provides a roadmap for those who are called to the noble task of conveying the message of Islam with wisdom, compassion, and integrity (pp. vi-vii).” This book is spread over five chapters, excluding a vast introduction, conclusion, appendix, and an epilogue to the protocols. In his detailed introduction, the author draws an outline of the fundamental concepts and basic principles of Da‘wah. He introduces Islam as a peaceful religion and argues that it provides a solution to the problems of mankind.

Furthermore, it discusses the relation of Da‘wah with communal harmony and mutual co-existence. Similarly, it also analyzes conceptions such as the essences of Wahy (revelation) and Risālah (prophethood), the dichotomy between rational and revealed knowledge, and characteristics of a Dā‘ī. This section also highlights the historical perspectives of Da‘wah during the al-Khilafah al-Rashidah (Caliphate period) and Da‘wah in contemporary times from a global context.

Chapter first, Da‘wah and its significance, delves into the meaning and definition of Da‘wah. The author here focuses on the different dimensions of Da‘wah, such as ways and means, objectives, importance, causes of decadence, language and media of Da‘wah, and role of Da‘wah organization. Dr. Zargar is of the view that “the primary aim of a Da‘wah organization is to unite the disarranged Ummah into a unified whole once again (pp. 25-26). The author emphasizes Da‘wah, both individual and collective Da‘wah programmes, keeping a view of a particular place’s circumstances and social order. He argues that the prophet Muḥammad (SAW) preached the message of Islam both individually and in public. However, he asserts that there must be an organized group of individuals who can understand their responsibilities and perform Da‘wah, and he substantiates his argument with the āyat (verses) of the Qur’ān and ahadith. Dr. Zargar points out that the role of an organized group is not merely to perform the activities of Da‘wah but to play his role in “construction and deconstruction simultaneously” (p. 125).

Chapter second, a brief historical survey of the development of Da‘wah methodology, is through examination and analysis of Da‘wah from historical perspectives and early methods. The author divides Islamic Da‘wah into three major historical phases; the initial phase discusses the early Islamic Da‘wah that started from the mount of Ṣafa and was carried out during the whole time of the prophet Muḥammad (SAW). Dr Zargar believes that Da’wah’s scope, significance, and relevance grew gradually and substantiates his claim from the different āyat of the Qur’ān (p. 132-34). The second phase discusses Da‘wah in the period of al-Khilāfah al-Rāshidah as a state responsibility. This phase emphasizes the status of Da‘wah as an obligatory duty for the rulers and examines scholarly opinions. The third phase elucidates the decline of activities of Da‘wah at the governmental level and becomes more concerned at individual and collective or group level. However, Da‘wah continues to remain the duty of a Muslim. The author notes that the most crucial part of this phase is that throughout the first century of Muslims, the activities of Da‘wah remained peaceful, and no force was used to convert people to Islam (p. 140). The author has quoted many historical events that support the fact that Da’wah activities were peaceful. For instance, he evidently discusses how Berke Khan and other Mongols accepted Islam despite terrorizing Muslim lands. Therefore, the events in which Tartars became Muslim have been explicitly considered turning points in Muslim history. The concluding part of this chapter discusses the spread of Islam in India and the major factors responsible for the emergence of Islam. However, this section has been discussed briefly and needs further elaborations to substantiate the claims pertaining to major factors responsible for the spread of Islam in India.

Chapter third, ‘the contemporary Da‘wah movements’, discusses four major Da‘wah organizations in the contemporary era, such as al-Ikhwān al-Muslimūn, Tablīghī Jamā‘at, Jamā‘at-i-Islāmī and Ahl-i-Ḥadīth movement of India. The chapter’s main subject remains in discussing historical settings in which Da‘wah movements emerged, their ideologies, objectives, approaches, basic principles, contributions, activities, methodologies, and achievements and weaknesses to Da‘wah activities. For instance, the author states that the founders of al-Ikhwān al-Muslimūn have realized that Westernisation is a threat to Islam, which can be countered by returning to the basics of Islam (p. 153). Similarly, the author argues that the purpose of Jamā‘at-i-Islāmī was to establish a “theo-democratic state” yet to be found (p. 166). Regarding Tablīghī Jamā‘at the author has made a comprehensive analysis and focused on its major activities and hallmarks, purpose, and methods of Da‘wah. Dr. Zargar is of the opinion that while other Da‘wah movements focused on producing literature alongside their activities in the field Da‘wah, the Tablīghī Jamā‘at did not consider writing books any of the means of Da‘wah. However, they are very concerned about working in practical fields. Subsequently, a lucid analysis of the Ahl-i-Ḥadīth movement of India and other movements has been conducted. Dr. Zargar made mention of Ahl-i-Ḥadīth movement in Kashmir and highlighted its role in the reformation as well.

Chapter four is dedicated to the communicational perspectives of Da‘wah and highlights the basic qualities of a Dā‘ī and Mud‘ī, such as language, attitude, knowledge, organizational qualities, discipline, and righteousness. Similarly, the fifth chapter of the book focuses on Da‘wah in the contemporary global society. The author discusses here globalization from the Islamic perspective, post-modern materialistic society, concepts such as the definition of man in Islam, problems of materialism, individualism, and the decline of the West. Dr. Zargar has also highlighted the problems, concerned with Dā‘ī’s, the importance of Ijtihād in Da‘wah and education system, Da‘wah and women, following the law of land, nationalism, and Muslim politics as well. It is pertinent to mention that this work presents a thorough analysis of the contemporary position, aims, and objectives of the Zionist movement, formation of UNO, the establishment of the Kingdom of Israel, and economic institutions and multinational companies to support the causes of Israel are debatable issues discussed in Da‘wah and the Contemporary Global Society.

In sum, Dr Zargar argues that Islam is indeed the religion of Da‘wah. He asserts that Da‘wah is the real force behind the success of Islam and Muslims. Therefore, he offers some ways to continue Da‘wah in the contemporary era, such as inter-religious dialogue, debates, freedom of choice, and essay competitions. The book’s appendix is another valuable contribution because it discusses the Jewish protocols, which consist of 24 documents containing the most comprehensive programmes for world subjugation published in 1905. The author’s lucid explanations and examination of the protocols expose the aims, purposes, and approaches of Jews to the rest of the people of the world whom they called Gentiles. An epilogue to the protocols traces the need and significance of Islamic Da‘wah and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. In sum, the book is a comprehensive guide and a valuable edition in the related field for students and researchers.

- The author is a Doctoral Candidate, Comparative Religion, Department of Religious Studies, Central University of Kashmir

source: http://www.kashmirobserver.com / Kashmir Observer / Home> In-Depth Review / by Guest Author / April 20th, 2024