Patna, BIHAR :

Eminent educationist Professor Qamar Ahsan

It is rarely that a person becomes the Vice Chancellor of four universities. Professor Qamar Ahsan, who was born into a middle-class family and started his education in Madrasa, is one such person.

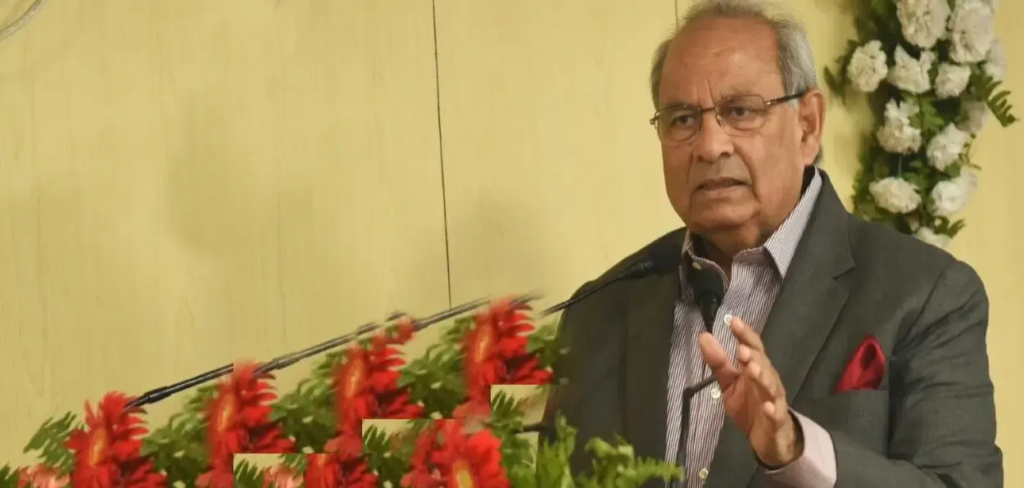

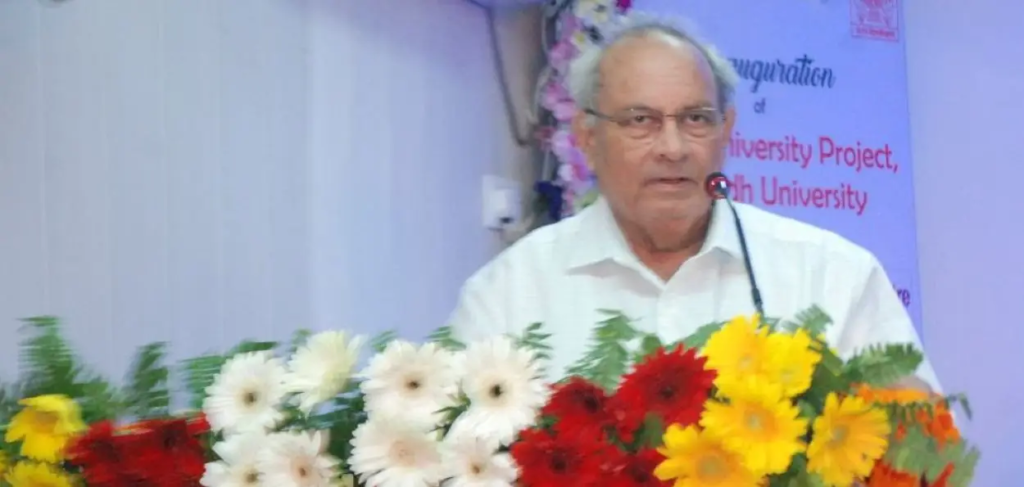

Professor Qamar Ahsan is a top-ranking educationist and economist, who holds the distinction of being the vice chancellor of four universities. Speaking to Awaz-The Voice, Professor Qamar Ahsan said that he not only brought changes in the educational system but also started new courses, especially job-oriented ones for the benefit of students in all the four universities.

Qamar Ahsan became the Vice-Chancellor of Maulana Mazharul Haq University, Patna at its inception stage. He played an important role in shaping the University campus, curriculum, and ethos. Generally, it was believed that the path to education in a University or seminary is linear, but I believe, it should be dynamic and both the curriculum and pedagogy should change periodically. This will make the students ready for jobs and thereby increase their employability.

Speaking about his early life, Qamar Ahsan said he was an ordinary student but quite active. “I always worked with complete confidence, even today my method is the same,” he said.

Prof Qamar Ahsan with President Ram Nath Kovind

Qamar Ahsan says that self-confidence is an emotion that gives a person the courage to succeed in the environment of a comprehensive culture. “My father was in the police and he often said that everyone should live and work together. At my home, I was raised in an environment where there was no scope for hatred or negativity. We were brought up in an inclusive culture and in later days not only fostered mutual brotherhood and goodwill but also studied and grew up living with people of different religions.”

He said that it helped him as his friends (from other religions) also supported him. Prof. Qamar Ahsan has worked with many governors and is familiar with the Madrasa, School, and College education system and has worked on improving these institutions.

“When I was the Vice-Chancellor of Maulana Mazharul Haq University, I tried my best to implement modern science in madrasas, although I was not fully successful, we connected hundreds of madrasas with the university and it improved the standards of education there. I succeeded in changing the environment in the madrasa.”

Professor Qamar Ahsan was born in April 1952 in Patna. He is the fourth among seven brothers and sisters. His father Syed Muzaffar Ahsan was in police service and he retired as an Additional SP.

Prof Qamar Ahsan with his parents and siblings

According to Qamar Ahsan, their father also received a medal for his good service in the police service. “We belong to a village in Siwan district of Bihar. When my father was in the police service, he was constantly transferred and I could not study in one place. I studied in different cities and schools,”

Qamar Ahsan says that at the time he was in primary, his father was posted in Ranchi where he was admitted into Madrasa Islamia. Thus his formal education started from a seminary. Next, his father was posted to Muzaffarpur CBI, so he joined a Pathshala. He then joined an English medium school and later the famous Miller School This trend continued and finally, Qamar Ahsan joined Patna College for higher education.

Prof Qamar Ahsan says Patna, the city of his birth, was quite famous for its educational institutions. “One of these was the Patna University. At that time this university was well respected. I was admitted into the Patna College.”

According to Qamar Ahsan, when he reached Patna College and Patna University, he could understand life from a different perspective. “I did my BA and MA in Economics. I was an average student but very sensitive about my course and my studies.”

The Patna University, education was quite good; it charged a nominal fee and the University Library was a treasure trove. “I used to read non-syllabus books more than my course books. My father also encouraged me in this regard and I started reading a lot of novels and story books. I read Premchand and Ismat Chaghatai and in between I also read a lot of English novels. This broadened my horizons of thinking and understanding.”

He said that at that time JP (Jay Prakash Narayan) Moment was at its peak and he too joined it. He earned her doctorate from Ranchi University. “In the meantime, after MA, I got a job at Magadh University in 1977. Although my father had wanted me to join the civil services, I always wanted to be a teacher. So when I joined the college as a teacher, my dream had come true. I was quite happy and excited. I wanted to share my experiences with students and take practical steps to improve the system.”

Prof Qamar Ahsan with his wife, children and grandchildren parents and siblings

Interestingly, Qamar Ahsan’s grandfather was the Head Maulvi at Chapra District School. ‘I had the experience of studying in different schools and mentally I was passionate about teaching. When my dream became a reality, I turned my full focus to teaching students and improving their academic standards. Then I got transferred to AN College, Patna, and was promoted as a Reader. Since then I never looked back and received promotions regularly.”

He first was appointed the registrar of Nalanda Open University, then Veer Kaur Singh University, and Maulana Mazharul Haq University of Bihar

Given his excellent educational experience, the government appointed him the Vice Chancellor of the BN Mandal University, Madhapura. He remained in the post from 2006 to 2008.

During this period he made the university clear a huge backlog of examinations and corrected the system. He tried to improve the attendance of teachers, and students; establish an educational environment, and promote curricular and extra-curricular activities in the campus and colleges under its jurisdiction. He introduced job-oriented courses in the university as well as improved the financial condition of the institution.

Prof Qamar Ahsan says,” I was given an opportunity to become the vice chancellor of various universities and in the meantime, I tried to provide job-oriented courses to the students so that their migration could also be stopped. Bihar students usually go abroad for job-oriented courses, I tried to start the same courses for which they would go abroad.”

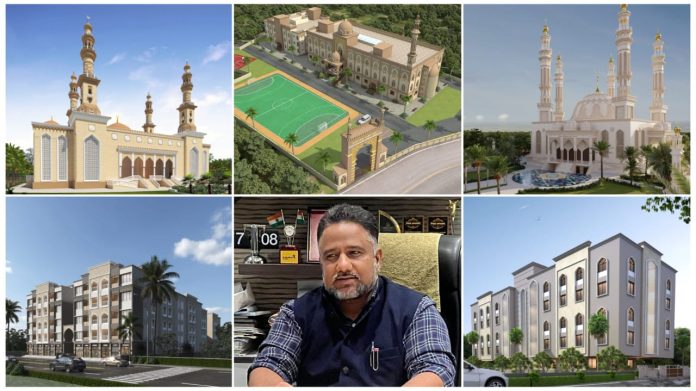

In 2008, Professor Qamar Ahsan was made the Vice Chancellor of Maulana Mazharul Haq University, Patna. When he came to take charge, the University was in a small government building on Bailey Road, Patna. The Maulana Mazharul Haq Arabic and Persian University was established in 1998 and despite the appointment of three Vice-Chancellors, it did not take off till 2008. It was a University on the papers.

Prof Qamar Ahsan with Sushil Modi while inaugurating a University

Qamar Ahsan says, “I formulated a plan of action and the university was functional within three months. Today, more than 20,000 students are studying in different departments at this university.”

He said that the University has more than four dozen Knowledge Resource Centers throughout Bihar and arrangements have been made to provide regular education to 116 higher education institutions near Madrasas and Fazil.

The university has a strong management of teaching as well as training. Professor Qamar Ahsan was the Vice-Chancellor of Maulana Mazharul Haq University till 2011.

Mazharul Haq University started various courses at that time, in which BBA, BCA, BJMC, MBA, B.Ed, etc. are noteworthy. He said that this university was also related to madrasas, so in the meantime, I tried to correct the higher education system of madrasas, but some people did not approve of it.

Professor Qamar Ahsan says that my experience with madrasas is that there are two types of madrasa, one is a madrasa where religious education is given and the other is the one where all subjects are taught. I believe that normal education should also be introduced in the former while in the latter category, the curriculum needs to be modernized to make the alumni job worthy.”

He said that the curriculum and teaching method should be changed from time to time.

“When I was the VC of Maulana Mazharul Haq University and during my visits to the madrasas, I noticed that students showed up only on the day I visited these. That too only 50 percent of the students were present.”

Prof Qamar Ahsan delivering a lecture

This would change if the curriculum included research. “If there is a research curriculum then the students will benefit and the subject should be taught as per the demand of the market.”

After Maulana Mazharul Haq University, Prof. Qamar Ahsan became the Vice Chancellor of Sidhu Kanhu Murmu University, Dumka, Jharkhand and then of Magadh University.

Meanwhile, according to his vision, he continued to solve the problem of education quality of students, better university system and teachers. Qamar Ahsan is the author of about 9 books and more than 30 of his papers have been published in major journals of the country. He has been a member of the editorial board of NCERT, IGNOU and various journals. Professor Qamar Ahsan says that whether a student is successful or reaches a position, he should not forget honesty and hard work. Only those people who have the confidence and passion to do something achieve success in life.

Prof. Qamar Ahsan was born and brought up in Patna, son of Syed Muzaffar Ahsan and Nafis Fatima Naqvi. He has distinguished himself as an educator, educational administrator and educational innovator. He said that by the 10th class, every child should make his own goal of what he wants to do in his life. “People who do not fix their goal often fail,” Qamar Ahsan says.

He says he had made his goal clear as soon as he passed matriculation and it was he wanted to become a teacher.

Professor Qamar Ahsan got married in 1980, he has two children and his wife is also a school teacher. The elder of the two children, the daughter has shifted to the Netherlands and the son lives with them. He said that they are seven brothers and sisters. Four are in the US, and one is in England.

According to Qamar Ahsan, he had also shifted to the USA and had obtained a green card. However, due to his mother’s health, so returned and then decided to continue his services for the country.

Although most of his family has shifted abroad, Qamar Ahsan says he is satisfied with his life.

source: http://www.awazthevoice.in / Awaz, The Voice / Home> Story / by Mehfuz Alam, Patna / May 30th, 2024