Aligarh, BRITISH INDIA / Noida, UTTAR PRADESH:

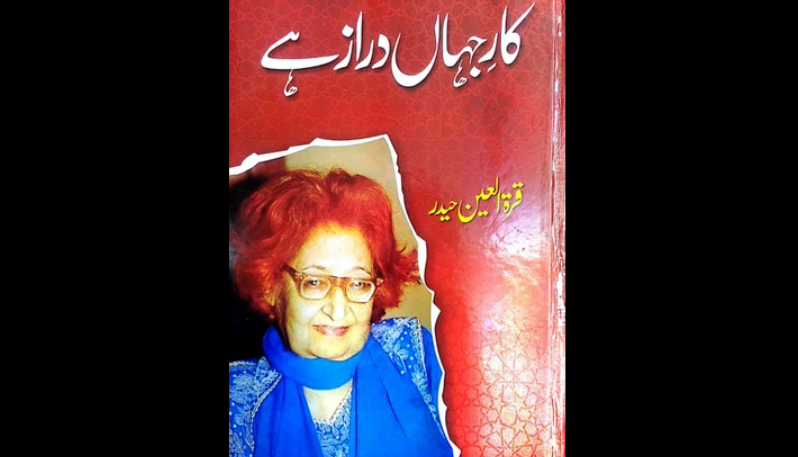

On Urdu writer Qurratulain Hyder’s 95th birth anniversary on January 20, remembering her last classic novel, Kare Jahan Daraz Hai, which is a treat in style and content.

Kare Jahan Daraz Hai (The business of the world goes on), Urdu novel in two parts, bound in one volume, Qurratulain Hyder, Educational Publishing House, Delhi, First edition 2003, Pages 766, in large size, Price: Rs 600.

One of the most significant novels of Urdu writer Qurratulain Haider, Kare Jahan Daraz Hai, is the winner of India’s highest literary award—the Jnanpith. Hyder is known for her magnum opus, Aag ka Darya, which has been translated in many languages. She herself translated it in English as River of Fire.

Kare Jahan Daraz Hai is perhaps her last published novel in her journey which started with Mere Bhi Sanamkhane, her first novel, published in 1949. Incidentally, most of her novels have been translated and are popular in Hindi, except her first and the last.

On my Facebook page comments, I got to know that her novella Sitaharan is also well rated by her readers.

Apart from her above mentioned novels, Hyder has to her credit-Safina-e-Game Dil-1952, Patjhar ki Awaz (a short story collection)-1965, which fetched her the prestigious Sahitya Akademi award in 1967, Roshni ki Raftar –1982, four novellas — Chay ke Bagh, Sitaharan, Agle Janam Mohe Bitiya na Keejo and Dilruba and Aakhri Shab ke Humsafar (Travellers of Last Night).

Hyder, who had to her credit 12 novels and novellas, four collections of short stories, many translations from classic world literature, worked as journalist with magazines Imprint and Illustrated Weekly of India and also taught at Jamia Milia Islamia and some US universities. She was offered a Sahitya Akademi Fellowship in 1994 and awarded Padma Bhushan in 2005. She also received the Ghalib award and Bahadurshah Zafar award.

Hyder was born on January 20, 1928 to Sajjad Haider Yildarim and Nazar Sajjad Haider, both Urdu writers. She started writing at the age of 11 and wrote her first novel, Mere Bhi Sanamkhane, at the age of 19, which was published, when she was just 21 years old. After Partition, she migrated to Pakistan, from where her most significant novels were published. She returned to India after many years and lived in Delhi. She passed away on August 21, 2007 at the age of 79. She did not marry and was perhaps against the institution of marriage.

Kare Jahan Daraz Hai (the title chosen from a couplet of Iqbal, who along with Faiz Ahmed Faiz is idolised by writers and people in both India and Pakistan) and is an autobiographical novel, focusing on Hyder’s long family history. She has delineated the family history from 740 A.D to almost 20th century-end. The first part of the novel depicts family history from 740 A.D to 1947 in almost 440 pages and 11 chapters, while the post-1947 family history is covered in the second part in 310 pages and five chapters — a total of 16 chapters.

It was in 1962, while visiting her ancestral house in Mohalla Sadaat, Nehtor/Nehtur, Bijnor district in Uttar Pradesh, that the idea struck to Hyder to write novel on the history of the place. She goes back to Zaid, her ancestor in 740 A D, who went to Georgia, established their rule in Tabristan , made Tirmiz their nation, and if they had not moved toward Hindustan in 1180 A D from Turkmenia, they would had been part of the then Soviet Union, she writes.

The story begins from the city of Tirmiz and the second part of the chapter moves the story from Jehon to Jamuna when the family comes to the ‘country of Shakuntala’ and settles somewhere near Kumaon and Garhwal. The Tirmizi family gets land there and makes a new beginning. Members of the family serve kings and one member of the family follows Emperor Aurangzeb in his pursuits.

Hyder has collected documents from family and archival sources to write an authenticated history of her family in narration form, which makes it an extremely readable historic/autobiographical novel. In the first chapter itself, the story reaches the 1857 revolt against the British, in which one rebel, Mir Ahmad Ali, from the family joins the rebellion, while the others remain loyal to the British. The narrator cites some events of the rebellion, particularly in Bijnor district, through documents and family stories.

Every chapter has been provided with references in the end, rather unusual for a novel. In the first chapter’s reference, it has been mentioned that Zaid Bin Imam Zean Albadan was martyred in year 744 A D. Mir Ahmad Ali Tirmazi of this family gave his life in the 1857 revolt as he was executed.

The writer refers to river Gagin, passing through Nehtor and going toward Moradabad. In fact, the story of the family from 740 AD to 1857, is just referral, the novel focuses upon 1857-1947 in first part of the novel and 1947-1987 in second part of the novel.

Hyder’s narration is filled with historic references and depiction of nature, like mentioning rivers like Gomati, Ramganga and Ravi, which makes the novel interesting in its style. She refers to her grandparents, but the real story of novel moves from the depiction of her father Sajjad Haider Yildaram and mother Nazar Baqar’s life story from the days of their school to the end of their lives, which carry on in the second part of the novel as well.

The story of Sajjad Hyder is also the story of development of Muslim educational institutions and the story of women’s education among the Muslim community. It is a fascinating story of the development of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) as well, which became the base of enlightenment among Muslims in pre-Partition India.

Hyder’s mother’s development as an Urdu fiction writer and father Yildaram’s development as a diplomat, writer and traveller, create an aura of romance for that period of history. Yildarim was fond of travelling and moved around many countries, particularly in West Asia. Hyder got the thirst for travel from her father and she, too, travelled many parts of the world.

The novel is full of her travelogues as well and particularly interesting is her description of Egypt during Gamal Abdel Nasser’s regime, changing into a modern nation. Her depiction of the Nile River, Egyptian Mummies, Alexandria, Suez Canal, assertion of independence from the West by Nasser, are all narrated in fascinating style. She describes the geo socio-cultural-natural locale of all places in a manner that transports the reader there.

In the second part of the novel focusses on life in Karachi, where Hyder had migrated with her family. Here she grows into a celebrated writer, who goes through much turmoil as well. There are petty attacks on her writings, she has a casual and carefree temperament, and does not bother about the malicious attacks. She had strong support from friends and family.

Poet Faiz ‘s appreciation and attachment with her family is described so is author Sajjad Zaheer’s underground life in Pakistan mentioned. Hyder spent a lot many years in London. She exposes the Pakistan government’s anti-woman attitude and bureaucratic favouritism.

Affectionately called Ainee Apa, Hyder ‘s return to India was not melodramatic; rather she makes it look casual and matter of fact, does not damn Pakistan, just comes back and faces almost similar struggles as in Pakistan.

This novel seems to have been translated and published in Hindi by Vani Prakashan, Delhi, in Hindi in 2020 at a prohibitive price of Rs 5,000 with an introduction by Gopi Chand Narang, but the same can be downloaded free as a pdf file from Urdu Digest Novels website.

When I read this novel, its Hindi or English translations were not available and, with my too slow speed in reading Urdu, it took me few months to complete it. But, this was the one of the best reads I have done in my life.

The writer retired as professor in Hindi translation from Centre of Indian Languages, JNU, New Delhi; was Dean, Faculty of Languages, at Panjab University, Chandigarh, and at present is honorary advisor at Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre at Delhi Archives. The views are personal.

source: http://www.newsclick.in / News Click / Home / by Chaman Lal / January 20th, 2023