INDIA:

A new book questions political wisdom about competitive communalism before and after Independence.

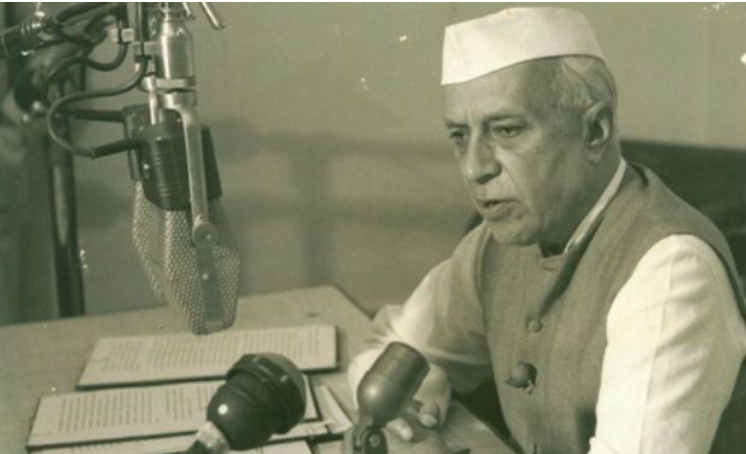

The prevailing political wisdom of the day is to chastise Jawaharlal Nehru, his Congress party, and their inclusive vision for the republic. Given this, one is caught in a fix if a published work subjects the Congress-Nehruvian performance to criticism. The republican and constitutional vision of India, and its plans and goals were outcomes of a prolonged anti-colonial mass agitation, which multiple ideological and identitarian political formations joined, complemented and contested.

Besides the aligned or contending forces, intellectuals and activists of various 19th and 20th-century hues also provided inputs. Privileged Muslims articulated some strands, including the exclusionary right-wing politics of communal separatism. Though represented by the Muslim League, and its sole spokesman MA Jinnah, they straddled nearly every shade of political articulation, ranging from Left to Centre, from those who advocated separatism to its vociferous opponents.

Unfortunately, the academic and popular domains popularise Muslim separatism more than their resistance to separatism. Academic studies also focus too much on Uttar Pradesh (earlier the United Provinces of Agra and Awadh). Gyanesh Kudaisya (2002) characterised this province as India’s heartland in terms of population and geographic size but also narrative-making for the Indian polity.

The former landed elites of the Muslims of this region, whom David Lelyveld (1978) called the “Kutchery Milieu”, were in the forefront and mainstay of the Muslim League. An important Muslim League leader from Lucknow, Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman (1889-1973), candidly and proudly proclaimed this in his 1961 memoir, Pathway to Pakistan. Quoting Maulana Azad, he writes, “All students of Indian politics know that it was from the U.P. that the League was reorganised. Mr Jinnah took full advantage of the situation and started an offensive which ultimately led to Pakistan.” Interestingly, in the late 1930s, Khaliquzzaman was the mayor of Lucknow and allied at least once with the Hindu Mahasabha. After Partition, it took him a long time to migrate to the other side of the border.

Against this backdrop, Aishwarya Pandit’s Claiming Citizenship and Nation: Muslim Politics and State Building in North India, 1947-1986, published by Routledge in 2021, is a critical intervention. She writes, “Given the demographic dominance of U.P. Muslims in some constituencies, the threat of revival of ‘Muslim communalism’ continued to impact their politics. In the colonial period, the United Provinces had remained central to Muslim politics around issues of representation, minority safeguards and language.”

Pandit disagrees with Kudaisya and proposes in her introductory chapter that the Uttar Pradesh Congress opposed the Centre’s move to “introduce minority and cultural safeguards after 1947”. Her book examines the intersections of law, identity and property and notes region-specific Muslim—and anti-Muslim—politics and articulations. Notably, she includes in her work the tensions that prevailed within the Muslim community over contemporary concerns.

Pandit says the new Muslim leadership that emerged after independence articulated the weaknesses of Nehruvian secularism, particularly concerning their religious, cultural and identitarian concerns. Further, from the mid-1970s onward, “Fatwa and Ulema politics acquired the centre stage”. Her study ends in 1986, a period that, according to her, “signaled the continuation of Hindu counter mobilisation, which set in the 1950s around the [Babri] Masjid-[Ram] Temple issue [of Ayodhya], the issue of minority appeasement and personal law and also coincided with the dipping fortunes of the Congress party in Uttar Pradesh”.

In her effort to discover reasons for the Congress party’s decline in Uttar Pradesh, she argues that Muslims here [and in Bihar] “made some surprising alliances including those with the Jan Sangh in the 1960s and 70s”. Pandit attempts to absolve Muslims of the responsibility for this, and “challenges the widespread view that Muslims acted as a secure and stable ‘vote-bank’ for the Congress after independence”.

This is where the book would provoke many to raise a few questions that have been left unasked or unanswered. Terminating the study in 1986—and not a few years later—may have excluded the author from raising some crucial questions. Hindu counter-mobilisation got massive support from the Shah Bano issue that raged from May 1985 to April 1986, other than the ‘nationalisation’ of the local Ayodhya dispute, which Pandit chooses not to examine. Scholars, even those not inclined to the right, often sidestep Muslim contributions to communalising narratives that fed Hindu majoritarianism, weakening India’s fragile pluralist secularism.

On 15 January 1986, at a Momin Conference session at the Siri Fort Auditorium in Delhi, then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi announced his intention to amend the law to nullify the Supreme Court’s April 1985 verdict in favour of Shah Bano. Driven out of her home in 1975, 43 years after her marriage, Bano had approached the courts seeking maintenance. Given instant triple divorce in 1978—inside a trial court in Indore—the case moved from the High Court to the Supreme Court. In May 1986, the Rajiv Gandhi-led government passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act following strident Muslim protests in January that year against the progressive judicial verdict that granted Shah Bano alimony. The law passed in Parliament reversed the maintenance the court had said she was entitled to.

The Urdu memoir, Karwan-e-Zindagi, published in 1988 by Maulana Abul Hasan Ali Miyan Nadvi (1914-1999), makes the conservative Muslim approach to this issue pretty clear. In Volume 3, Nadvi triumphantly writes about how he persuaded Rajiv Gandhi not to accept the proposition that many Islamic countries had reformed their personal laws. He rejoices in accomplishing his effort to stymie similar reforms in India. He says his arguments had a particular psychological impact on Rajiv Gandhi—“Woh teer apney nishaaney par baitha—My arrow hit its target”. Nadvi includes a candid confession: “Our mobilisation to protect the Shariat in 1986 complicated the Babri Masjid issue and vitiated the atmosphere in a big way—“Iss ney fiza mein ishte’aal wa izteraab paida karney mein bahut bara hissa liya,” he writes.

Nadvi admits in his memoir that he had promised to Rajiv Gandhi he would persuade the Waqf Boards to make an endowment available to maintain abandoned women. But this issue remains unaddressed until today. Aishwarya Pandit, rather than exploring the clergy politics of Lucknow’s Nadvi, jumps over to Delhi’s “Imam” Bukhari and his demagoguery and rhetoric.

Nadvi’s politics of 1985-1986 needs to be read with Nicholas Nugent, who writes in his book, Rajiv Gandhi: Son of a Dynasty, published by BBC Books in 1990, that the Congress High Command decided in early 1986 to play the Hindu card like the Muslim women’s bill played the Muslim card. Nugent writes, “Ayodhya was supposed to be a package deal…a tit for tat for the Muslim women’s bill…Rajiv played a key role in carrying out the Hindu side of the package deal by such actions as arranging that pictures of Hindus worshipping at the newly unlocked shrine be shown on television.”

On 1 February 1986, within an hour of the Faizabad district court judgment, the lock of the Babri Masjid was opened. The “deal” between the Prime Minister, the Muslim clergy and the Momin Conference’s Ziaur Rahman Ansari, who died in 1992, had been struck a month earlier. Ansari’s biography, Wings of Destiny, written by his son Fasihur Rahman and published in 2018, refers to this series of events. Yet, nagging questions remain: who wanted the locks opened and why? After all, elections were four years away, and Rajiv Gandhi did not have a direct electoral stake in the event, except for a few reverses in by-elections for the Congress party.

A sizeable section of Hindus was peeved after Nehru reformed, though more symbolically than substantively, Hindu Personal Laws in the 1950s, but left out Muslim Personal Laws. This aspect is brought out by Reba Som in February 1994, in “ Jawaharlal Nehru and the Hindu Code: A Victory of Symbol over Substance ?”

Put another way, what the votaries of Hindutva call Muslim appeasement is the State appeasing the conservative and patriarchic Muslim clergy. Quite often, liberal and left scholars and activists hold the position that reforms must emerge from within the Muslim communities. Nevertheless, competitive communalism adversely affected the Congress party in the electoral sphere. First, the ex-Socialist forces, comprising the backward classes and Dalits, replaced Congress with the Bharatiya Janata Party. Pandit disappoints on this count in her sixth chapter despite delving into primary archival sources on all issues raised in her immensely readable book.

In the third chapter, Pandit discusses Hindi-Urdu battles and blames the ruling Congress for the deficits in State support for Urdu. She misses out that the protagonists of Urdu in Uttar Pradesh also share some blame for the idioms and methods of political mobilisation they didn’t employ for the Urdu cause. Selma K. Sonntag (1996) provides a more informed comparative assessment of the Urdu politics of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Besides Urdu and personal laws, another central controversy has been the minority status of the centrally-funded Aligarh Muslim University. Pandit touches upon this subject but leaves out too much. She does not concern herself with the academic performance or research at the university, which has refrained from examining Muslim concerns such as communal strife, caste among Muslims, patriarchy, and Muslim under-representation. Just a few months before his unfortunate death in 2010, Omar Khalidi candidly raised these issues. Could these deficits possibly have contributed to the disjunctions between State and society as also between India’s Muslims and the Aligarh Muslim University?

Quite often, the ruling party had to yield to pressures from Muslim conservatives and reactionaries, perhaps because despite massive funding to the university, it did not foster enough progressive Muslim opinion-makers and leaders. If true, this would limit the university’s contribution to resisting competitive communalism and can explain why the support base of the ruling Congress deserted it, eventually leading to the rise of what scholars such as Edward Anderson, Christophe Jaffrelot and Deepa Reddy call Neo-Hindutva.

Possibly because of this omission, this book does not help figure out why Uttar Pradesh Muslims could not throw up the kind of ‘Pasmanda movement’, or the short-lived Left-inspired gender movement Tehreek-e-Niswan, which emerged in adjacent Bihar in the 1990s.

Why Muslims in Uttar Pradesh failed to strengthen post-independence movements for citizenship rights and confined themselves to emotive religious, cultural and identitarian issues is a vital but unanswered question. Thus, this book ignores this pertinent question: to claim citizenship, and for the secularization of the state and society, how to strike a balance with rights for religious communities? This approach of the author doesn’t allow her to deal, even when discussing Muslim assets, with why Uttar Pradesh Muslims did not employ their wealth for capacity-building of their community, as South Indian Muslims did and still do, in the spheres of education, and health? Why did they remain highly dependent upon the State?

Notwithstanding these limitations of perspective, Pandit’s considerably well-researched book delves into untapped and under-tapped primary sources. Her analysis of a wide range of evidence and her articulation is lucid. True to its claim, it is a valuable contribution toward understanding post-independence Uttar Pradesh.

The author teaches modern and contemporary Indian History at Aligarh Muslim University. The views are personal.

source: http://www.newsclick.in / News Click / Home> India> Politics / by Mohammad Sajjad / February 20th, 2023