KARNATAKA :

Nettara Sootaka by Rahmath Tarikere is a collection of articles written for different occasions in the last five to six years on contemporary writers and issues

What it means to write in Kannada at present as an intellectual or, to be more specific, as a literary and cultural critic? Keeping this question in mind, I would like to introduce Rahamath Tarikere’s Nettara Soothaka: Dharma, Rajakarana, Samskriti, Sahitya (Spectre of Bloodshed: Religion, Politics, Culture, Literature), a collection of articles written for different occasions in the last five to six years on contemporary writers and issues.

Rahamath Tarikere, one of the makers of cultural criticism in Kannada, has been a prolific writer. His research into the culture of Sufis, Nathapantha, Shakthapantha and Moharum of Karnataka is an exemplary field-work investigation in Kannada scholarship. Apart from travelogues, his scholarly engagements encompass writings on literary texts and cultural issues, literary criticism, research methods, edited volumes on Kannada literature, and interviews of intellectuals among others. He works largely in the field where literary and cultural studies intersect.

Tarikere has kept his writerly life alive by contributing pieces to journals and periodicals, and the present book, the sixth of his collected writings, consists twenty-two articles. Six articles in the early part of the book are reminisces of writers after their death.

Among these, Tarikere’s observations on the life and works of U. R. Ananthamurthy, Gauri Lankesh, Vasu Malali and M.M. Kalburgi are worth reading.

“Ananthamurthy: Kashtakalada Naitika Dani” (Moral Voice of Hard Times) — one of the best tributes to Murthy I have ever read in Kannada — delves deep into his intellectual and political complexities. Tarikere is at his best in identifying the archaeology of Ananthamurthy’s thought as ‘resistance’ (to structures of power and fascism), ‘dialectical mode of analysis’ (Right-Left, Kannada-English, Brahmin-Shudra, etc.), ‘dialogic’ and ‘transgressive’ (going beyond). Similarly, “M.M. Kalburgi: Kalakelagini Agnikunda (Fire-Pot beneath Feet)”, written in academic style, explores the philosophical underpinnings of Kalburgi’s research work against the larger backdrop of violence and intellectual life today.

This is a major point of departure for those interested not just in Kalburgi’s work but in Kannada research in general. Further, the portraits of writers and other eminent personalities including Dr. Rajkumar, celebrated Kannada film actor, Jawaharlal Nehru, N. K. Hanumanthaiah, B. M. Rasheed, Ramadas, H. S. Raghavendra Rao and A. K. Ramanujan have been sketched informatively in plain and clear prose.

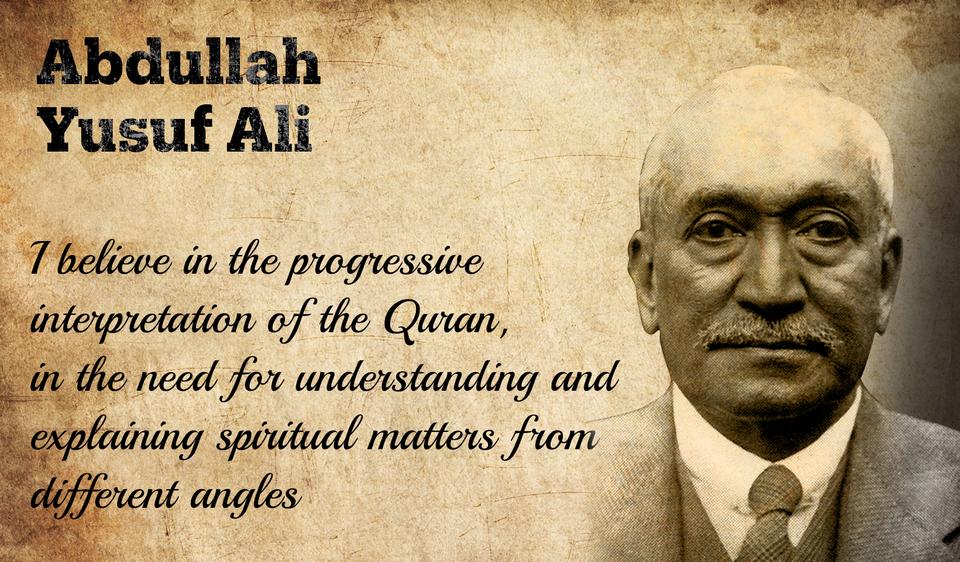

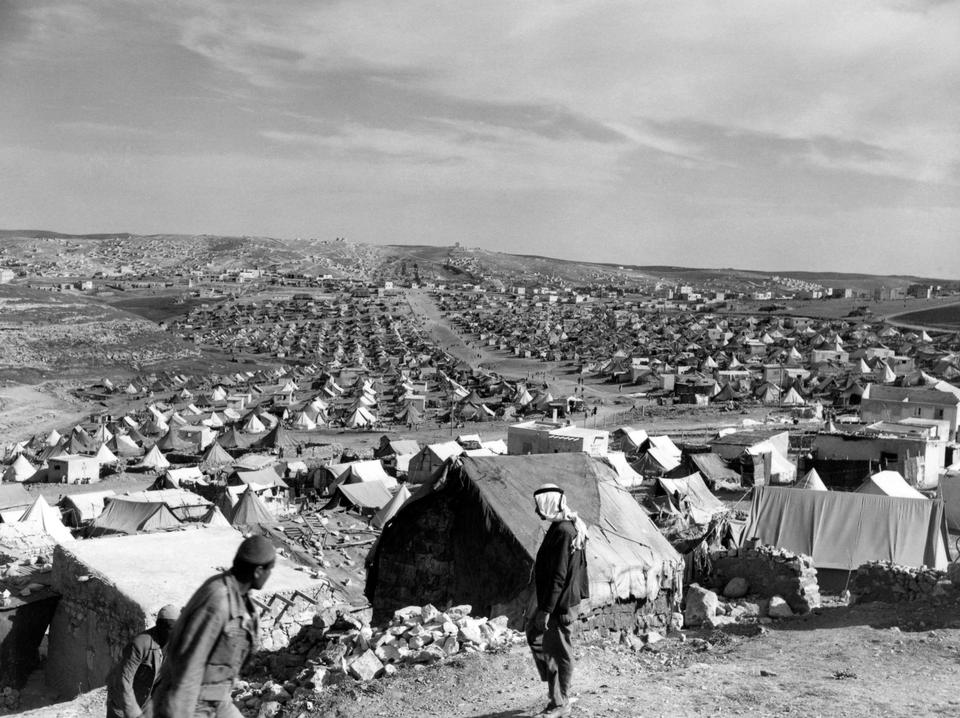

The articles on Muslim and Sufi culture give a detailed account of the Muslim way of life in India. “Muslimarigobba Ambedkar Agatya” (Muslims Need an Ambedkar) and “Muslim Samudayada Sankathanada Tathvika Nelegalu” (Philosophical Foundations of Discourse on Muslim Community) and “Muslim Samskrutikalokada Swarup”(The Nature of Muslim Cultural World) unfold the dynamics of Muslim identity politics, socio-historical problems of Islamic culture and the formation of different discourses on Muslims. Those interested in understanding the nuances of Sufism and Islam will find these articles enormously useful.

One more article which deserves our attention in the collection is “Hyderabad Karnataka Sahitya: Chaharegalu” (Literature of Hyderabad Karnataka: Traces). It raises an important question about literary culture: what is the relationship between literary expression and its geo-political conditions? While sketching the uniqueness of literary culture in the region of Hyderabad Karnataka, Tarikere shows how it is unique and different from literary cultures in Dharwad and Mysuru regions. His insights in this article open up further scope for in-depth investigations into Kannada Literary Studies.

Overall, the articles in the book try to diagnose what ails our times, particularly how writing and intellectual life have become vulnerable. As the title of the book suggests Tarikere grasps it with the metaphor of bloodshed, modelled on how Sharanas problematized the interconnectedness of experience, acts and speech in ‘Nudi Soothaka’ (Spectre of Speech). The practice of Fearless Speech, according to Tarikere, has become the target of violence in the 21st century. In tune with this perspective, the book is dedicated to Dabholkar, Pansare, M.M. Kalburgi and Gauri. Throughout the book the reader can experience the author’s anxieties, concerns and aspirations about our socio-intellectual life in India. The book certainly contains some insightful articles which Kannada readers should not miss. However, some articles could have been left out from the selection. What is the rationale behind bringing out a collection of articles written for different occasions? A careful selection of articles, rewriting some of them when they go as part of a book and a long introduction that connects these articles on different themes would make the anthology more useful than merely compiling hitherto published articles.

Rahmath Tarikere’s prose, though wanting in liveliness, does not fail to convey what it intends to. However, his mode of analysis still remains largely ‘ideology criticism’, the modernist reasoning scrutinizing all types of issues. We need to go beyond the Marxist- ideology-critique and explore different forms of analytics as the nature of evil we are confronting today does not reveal itself easily to worn-out tools of analysis. It might be useful to examine cognitive structures of contemporary society, instead of resorting to ideology criticism. In this respect, a scholar like Tarikere can bank upon his own studies on Indian intellectual traditions such as Sufism, Nathapantha, Shakthapantha, etc. to develop new tools of analysis and grasp the reality differently, if not from the informed understanding of the western scholarship available in English.

If this project, further, calls for thinking how to shape the Kannada critical thought, I could not help but invoke the writings of, just to mention two critically important forerunners among several others, D. R. Nagaraj and Keerthinath Kurthkoti. The present Kannada literary and cultural criticism can fruitfully learn from their art of thinking, making powerful narratives and analysis.

Rahamath Tarikere also belongs to this tribe, and his individual talent certainly promises new modes of thinking and renewing this tradition.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by N. S. Gundur / September 05th, 2019