KERALA :

A vivid piece of maritime history is hidden in the memories of the cooks and deckhands who once sailed off the Malabar coast

By noon, the sun would heat up the vast blue expanse through which they sailed at great risk to their lives. By evening, when salt and dirt clung to their bodies, the skies would turn crimson, symbolising streaks of revolt. Later, weather permitting, the shimmering stars would give them clues to the voyage that lay ahead through the inky waters of the Arabian Sea, often to the Persian Gulf. On the shore, they would unload the goods they had loaded on to the wooden dhows: timber, bamboo, coconuts, tapioca, tiles, salt, sugar, fertilizers. And sometimes, hidden among the cargo, people . Being smuggled to the far shores.

But even when they returned to their homes in Kerala, none of the deckhands of the dhows wrote about their experiences; in fact they actively strove to forget this tempestuous period in their lives that ended when better transportation facilities arrived. It’s been nearly four decades since these traditional vessels with their distinctive masts set sail from the Malabar coast, either along the coastline or farther afield. But it’s only now that the world has begun to hear the stories of these intrepid men, an integral part of the maritime history of peninsular India.

And this is thanks to a photo artist from Kerala’s port town of Kodungallur, around which scholars speculate the ancient Muziris harbour existed until destroyed by the 1341 calamity. K.R. Sunil’s photographs, a series titled ‘Manchukkar — The Seafarers of Malabar’, captures the faces of 34 deckhands. It was on show last month at URU Art Harbour in Kochi. Through them we learn of the misery of people caught in a vortex of exploitation and unshielded from nature’s furies.

Bare frames

The faces are stark, the frames bare. But every black-and-white image tells a story. Of how poverty forced pre-teen boys to pack themselves off in an uru or sailing vessel on long-distance voyages battling rough seas and uncertainty for weeks on end, and then return home — if lucky — only to set off on another strenuous voyage. Years would pass, the boys would turn into middle-aged men. Then, seen as worthy of nothing else, plagued by ill-health, they would be sent home, discarded like boats with rotten hulls.

T. Ibrahim is now 80 and lives an unremarkable life in Ponnani, a fishing town in Malappuram district. He considers himself fortunate to have lived this long. As a youth, he recalls how he once sailed a dhow laden with tiles and a dozen sailors that got caught in a storm on its way to Ratnagiri in Maharashtra. Ibrahim joined his panicked colleagues and began jettisoning cargo. The vessel sank nevertheless. “Some of them managed to get away on a lifeboat. Ibrahim and four others held on to a piece of wood and floated for two days,” says Sunil, recalling his meetings with Ibrahim.

The youngest in Sunil’s photo series is also called Ibrahim, or simply Umboocha. Now 53, the man from Kasargod, along the Karnataka border, had his final sailing trips on motorised dhows in the 1990s. Memories of manchu, as the boat is called in his part of Malabar, where people also speak Tulu and Kannada, still make him shudder. Their vessel once sank during a cyclone when they were bound for Iran. They roped together emptied cargo barrels and drifted on the improvised float for three days. Rescue came, but they landed in jail: all of them had lost their identity documents.

Siva Sankaran, also from Ponnani, remembers that his first trip on a dhow to Bombay took seven weeks instead of four days. Reason: bad weather. But tempests were just one part of the deckhands’ ordeal, says Sunil. From starvation to sexual exploitation to unhygienic conditions to taxing work hours, the voyages were invariably hellish. “Circus in the seas,” is how Abdul Rahiman, 68, recalls them. “One had to climb 50 feet up on swinging ropes to set the sail. You may have to do it deep in the night, when the boat is violently rolling,” Sunil quotes the sailor as recalling.

The artist’s first trip to Ponnani was in 2014, though it was only two and a half years ago that he turned his focus on these deckhands of yore. “As a child, I had heard a lot about Ponnani. We had country boats with merchandise travelling there from Kodungallur.” The town charmed him on his first visit and inspired several more. The next time he brought his camera along. A photo series from these trips was shown at the 2016 Kochi-Muziris Biennale.

Steeped in pathos

Then, four months before the biennale, Sunil stumbled upon an old man singing a song to his friends. “There was something curious about its lines and the tune steeped in pathos. I thought I should explore more,” he says.

This was T. Ibrahim and this wasn’t the only sailing song he knew. He had learnt several from Rasakh Haji, a merchant of essential oils who owned the boat in which Ibrahim was a deckhand. Haji had a talent for creating songs and had composed one about the dhow. They sailed together from Mumbai to Kerala and “the ditties seeped into Ibrahim too,” says Sunil.

Most deckhands began their careers as cooks (pandari) when they just 11 or 12 and were routinely sexually exploited. Those who moved up the ladder became deckhands or khalasi. The capable among them rose to become captains or srank.

Abdul Lathif thought himself lucky to become a deckhand at 17, but is now repulsed by the memories. “The boat’s woodwork was always infested with roaches and scorpions. You would see them floating even in the drinking water. We were covered with lice. The winter winds gave us mouth ulcers,” he trails off. “After unloading the goods, we would appy a mixture of oil, lime and ghee to the boat’s keel to prevent barnacles. The work was done standing in a slush of mud and human excrement.”

C.M. Ummar was a young man during the 70s when he crewed in dhows carrying people looking for work in West Asia. Illegally. “A couple of hundred job-seekers would be taken aboard along with the cargo. You’d hide them with a tarpaulin. And in the high seas, another boat would come to fetch them,” he recalls. “Sea-sick, they would sometimes plead to be taken back home. Getting them back was equally dangerous.”

Deaths weren’t uncommon — whether from falling from the mast or from disease. Hussain, 64, recalls a friend’s demise: “With a heavy heart we offered prayers, and buried him at sea with a rock tied to his body.”

The primary duty of Muhammad Koya, 81, was to smear kalpath, a mixture of coconut-fibre, cow-dung, sawdust and ghee, on the keel to plug gaps. “It involved holding one’s breath under water for long periods; the job affected Koya’s hearing,” notes Sunil, who is now in the process of making a documentary on this bit of “ignored history”.

Floating bodies

P. Ummar is 20 years younger than Koya, and recalls how armed pirates would sometimes rob their cargo. “Such encounters were common along the Maharashtra coast,” he says. Koran, now an oracle for the traditional Theyyam dance in Kasargod, talks of the dead bodies he saw floating near the Bombay port during his manchu days. He suspects this was from the smuggler-customs encounters.

K.K. Kadar talks of how seasoned sailors would read signs of impending danger in “unusual changes in the colour of seawater, the rising froth, intertwined sea-snakes, dead fish…. they were indicators for the crew to prepare themselves for eventualities,” he says. Today, he is a public worker, and preoccupied with the 80th anniversary of a historic beedi workers’ strike that had once been held in Ponnani.

For T.V. Moideenkutty, too, life is calmer. The 54-year-old lives on the tranquil shore of Ponnani with his family in a tile-roof house. He started life as a cook in a dhow and then worked as a deckhand for eight years. At least it staved off poverty, he says, smoking a beedi.

Life on the dhow taught him a lesson: the value of drinking water. “I learned the word for water in many languages, especially before hitting ‘Hindistan’ during our Mumbai voyages,” he says, retying his mundu and tucking it in at the waist.

The lighthouse near Moideenkutty’s house stands tall with its gas flasher scanning the ocean. Standing outside URU gallery, I can see the sea dotted with gleaming new-age ships filled with crew and cargo heading out to harbours around the world.

The Delhi-based journalist is a keen follower of Kerala’s traditional performing arts.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu> Voyager> Society / by Sreevalsan Thiyyadi / April 13th, 2019

All photographs by Daniel Jacobius Morgan.

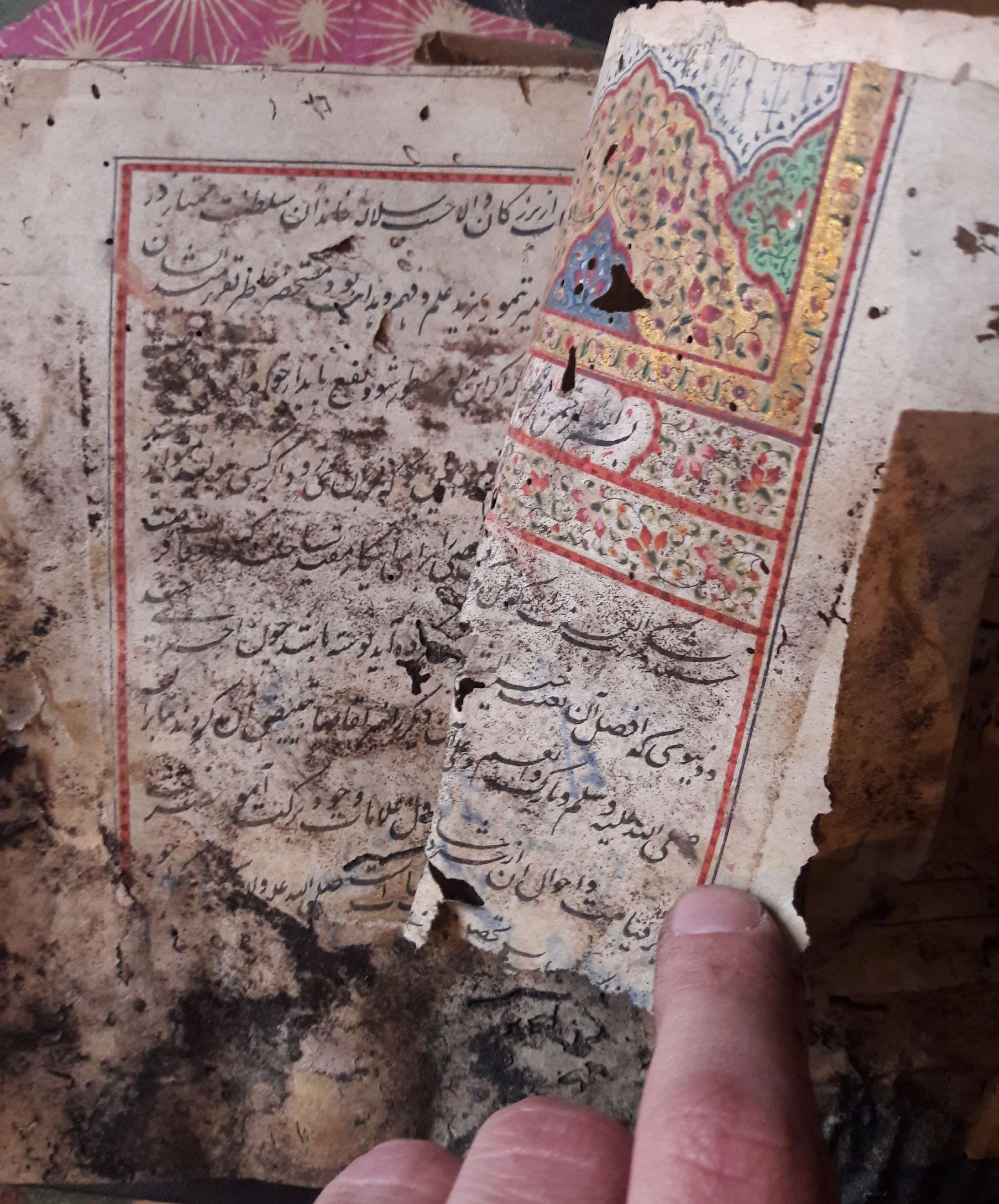

Daniel Jacobius Morgan is a PhD scholar at South Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Chicago.

source: http://www.scroll.in / Scroll / Home> Library of India / by Daniel Jacobius Morgan / November 25th, 2017