Lot 2•

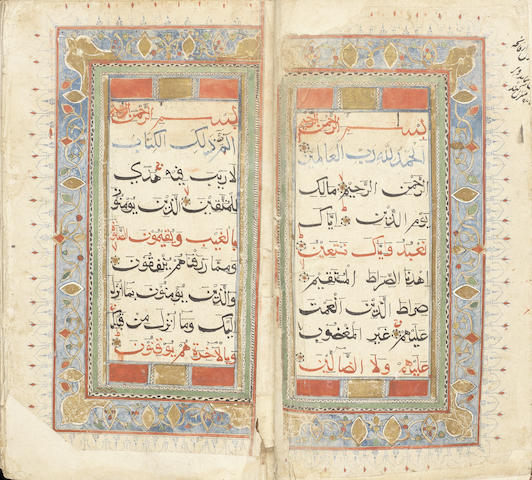

A LARGE ILLUMINATED QUR’AN, BY REPUTE TAKEN FROM THE BAGGAGE OF NANA SAHIB AFTER HIS DEFEAT IN THE MUTINY OF 1857

Sultanate India, late 15th/early 16th Century

Sold for £8,125 (INR 773,744) inc. premium

_______________________________________________________________________

A large illuminated Qur’an, by repute taken from the baggage of Nana Sahib after his defeat in the Mutiny of 1857, Sultanate India, late 15th/early 16th Century

Arabic manuscript on cream-coloured thin paper, 632 leaves, 11 lines to the page written in large and dispersed bihari script, first, sixth and eleventh lines on each page written in red ink, remaining lines written in black ink with diacritics and vowel points in black, the work Allah and some other significant words picked out in red, gold rosettes decorated with blue and red dots between verses, inner margins ruled in blue and red, catchwords, circular and pear-shaped devices in predominantly red, yellow and white coloured panels between suras left blank, two double pages of illumination at beginning and end with outer borders decorated with intertwining stylised floral and vegetal motifs interspersed with gold lozenges, edges frayed, some tears, corners rather thumbed, some waterstaining mostly restricted to outer borders, discoloration, later brown morocco with stamped central medallions and cornerpieces of paper onlay, with flap, edges torn, covers stained, rebacked

325 x 200 mm.

FOOTNOTES

Exhibited:

Portsmouth High Street Museum (unknown date, but probably first half of the 20th Century).

A typewritten label affixed to the flyleaf reproduces the exhibition note: Copy of the Koran from the baggage of the arch fiend of Bittoor, “Dundoo Punt”, Nana Sahib – the monster of Cawnpore. The Nana was a Hindoo, and this Koran was used to swear in his Mahomedan followers. Presented by Lieut. Gen. Harward, RA.

Nana Sahib, whose original name was Dhondu Pant, was a Maratha aristocrat, born in Bithoor, adopted son of the last exiled Maratha ruler, Peshwa Baji Rao II.

In the 1850s he became disenchanted with what he regarded as the East India Company’s high-handed policies, as well as, more immediately, its revoking the pension he felt he was due following the defeat and extinction of the Maratha kingdom.

In 1857 at Cawnpore (Kanpur) he switched sides, captured the Company’s treasury and declared loyalty to the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II and that he intended to restore the Maratha kingdom.

It is disputed whether Nana Sahib himself, or his subordinates, gave the order to murder 120 women and children (survivors of an earlier massacre) on 15th July 1857 at Bibighar.

But they were undoubtedly murdered, hacked to death by sepoys and others, and the bodies thrown down a choked well. Whatever the exact details, the incident, alongside others of 1857, became part of the mythology of the British Empire, and the cry of ‘Remember Cawnpore!’ passed into common parlance – seen even in the label in this manuscript – as a reflection of British views of Indian perfidy during the Mutiny (or Rebellion).

Nana Sahib disappeared after the Company retook Cawnpore. There were rumours that he lived on in Nepal, and became an ascetic; others that he died of fever.

Post-Independence he was lauded as a freedom fighter and there is a park in Kanpur in his honour.

According to David James (After Timur: Qur’ans of the 14th and 15th Centuries, The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Oxford 1992, pp. 102-107), ‘most of the Indian Qur’ans that have survived from the pre-Mughal period were written in bihari, a peculiarly Indian form of naskh whose origins are still obscure and which virtually disappeared with the advent of the Mughals.

In bihari script, the emphasis is on the sublinear elements of the Arabic letter forms, which are greatly thickened and end in sharp points. It is usually assumed the name of this script was derived from the province of Bihar in eastern India, but Bihar was not particularly important as a centre of Islam.

There is an alternative spelling, bahari, and it has been suggested that this is the correct form and that it is derived from the size (bahar) that was used to prepare paper for writing’.

James observes that the most frequently used colours in the illumination are a strong orange, a milky blue and yellow and motifs such as floral sprays, quatrefoils and chains painted in gold directly onto a blue ground.

source: http://www.bonhams.com / Bonhams / Bonhams.com> Auctions / London, Bond Street