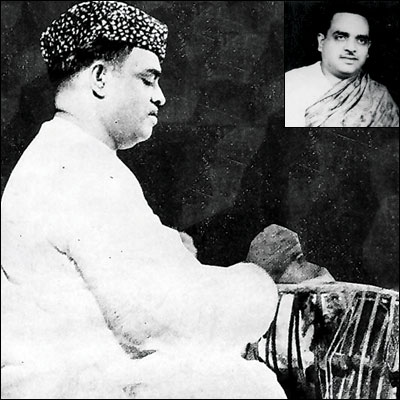

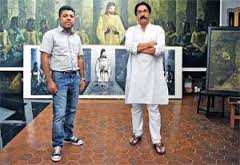

Grandsons or disciples? “Before we are grandsons of Sangeetha Kalanidhi Sheik Chinna Moulana, we are his disciples,” asserts Subhan Kasim. Speaking about his maternal grandfather and acclaimed nadhaswaram exponent is clearly a matter of great pride for Kasim, who with his younger brother Babu, was handpicked by the maestro to continue the family’s musical legacy.

Kasim and Babu meet visitors at ‘Alaphana’, the 1950s-era house in Srirangam that was formerly Sheik Chinna Moulana’s residence and is now Kasim’s home. A hot breeze stirs up the dry leaves outside, but the mood inside is one of quiet reflection. It will be 15 years this week since Sheik Chinna Moulana died at the age of 74.

“From 1982, after I graduated from college, until Thatha’s last concert in 1999 in Chennai’s Music Academy, where he was awarded the Sangeetha Kalanidhi title, I was performing with him,” recalls Kasim. “Thatha never had a retirement phase, he just kept working, or teaching.”

The Dr. Chinnamoulana Memorial Trust set up by Kasim and Babu will be hosting its 15th Shradhanjali (commemorative gathering) at Tiruchi this week.

Music in the veins

Originally from Karavadi in Andhra Pradesh, the family has over three centuries of experience in playing the nadhaswaram. “Thatha belonged to the Chilakaluripet school of music,” says Kasim, naming the town in Guntur district. “Among his gurus were his own father, Sheik Kasim Sahib, and later, Sheik Adam Sahib.”

Despite emerging as a noted performer in the Andhra style of Carnatic music, Sheik Chinna Moulana decided to explore the Thanjavur ‘bhani’ (school) which allows for greater variations in presenting ragas. “From an early age, Thatha was influenced by the recordings of T.N. Rajarathinam Pillai (1898-1956). He migrated to Tamil Nadu to get trained in the Thanjavur style of playing by the Rajam-Duraikannu brothers of Nachiarkovil for four to five years,” says Kasim.

Sheik Chinna Moulana’s career took off in the early 1960s, and Kasim believes it was the exposure to the Thanjavur ‘bhani’ that helped immensely. The maestro decided to make the pilgrimage town of Srirangam his home. Kasim, who accompanied his grandfather to Tamil Nadu early on, studied at the Srirangam Boys High School, and went on to graduate in Physics, at St. Joseph’s College, Tiruchi, while getting his music education at home.

Babu joined the in-house gurukul in his teenage years, and was educated up to Standard 8 in Andhra Pradesh. “We started our training with smaller versions of the nadhaswaram,” says Babu in halting Tamil, “Then, as we became older and and our hands grew accustomed to reaching all the fingering holes, we were given the regular-size instruments.”

The nadhaswaram, together with the ‘thavil’ drum, are often referred to as ‘mangala vadyam’ or auspicious instruments, showing their importance to sacred music in southern India.

The nadhaswaram’s use as a solely temple-based instrument for daily prayers and processions was slowly introduced to a more public and secular platform by royal families and later, the landed gentry.

“Nadhaswaram is an integral part of our society,” says Kasim. “Few occasions – weddings, housewarming ceremonies or prayers – are complete without its music.”

The days of concerts that would start late and go on past midnight are well and truly gone, says Kasim. “Artists today have learned to compress what was being done in four hours, to two-and-a-half. Most of the concerts these days are held from 7 to 9.30 p.m., which is a good duration. It allows more women to attend as well,” he says.

Concert exposure is as important to the artist as getting practical instruction, says Kasim. “I learned a lot about presentation and public relations while performing with Thatha,” he says. “These days, with overseas assignments, the artists must be prepared to interact with people of other nationalities too.”

Above all barriers

Kasim and Babu maintain an extensive audio-visual archive of their grandfather’s music concerts at home. Some video samples, such as Sheik Chinna Moulana and shehnai virtuoso Ustad Bismillah Khan exchanging ideas on fingering techniques on the two instruments, are shown to students of the Saradha Nadaswara Sangeetha Ashram, a school established by Sheik Chinna Moulana and today run by his family in Srirangam.

A typical day for the brothers starts off with breathing exercises (pranayama), and is followed by practice sessions on the nadhaswaram. Afternoons are reserved for vocal music lessons for the students, followed by instrument training in the evenings. “We spend the rest of the day in updating ourselves,” says Kasim. “Unlike before, there are hundreds of compositions being brought out these days, so as active performing artists, we must be familiar with what is going on in the arena.”

As to whether there’s any sibling rivalry during concerts, Kasim replies: “I support my brother when he takes the lead, and he supports me when I take the lead. There is no place for ego in music.”

The success of Muslim artists like Sheik Chinna Moulana and Bismillah Khan in a sometimes exclusively Hindu cultural sphere is a great example of India’s syncretism. Both the brothers, presently the special nadhaswaram artists of the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, feel that music is above matters of faith.

“Thatha often used to say ‘music is my religion; perfection is my aim.’ In northern India, most of the doyens of classical music are Muslims. You have the Kirana gharana, Bade Ghulam Ali, Roshanara Begum and so on. Those who speak of religion cannot ignore the contribution of the Mughal dynasty to the field; ragas like Malkauns, Amir Kalyani and Darbari Kanada all have an Islamic origin. Only those who are ignorant about music object to Muslims in the field,” smiles Kasim.

What is more pertinent is institutional support for classical music in India, he says. “The temple’s day begins and ends with nadhaswaram music. But increasingly, even big temples are doing without these musicians. The government should step in by paying exponents a decent salary and encouraging their employment,” says Kasim. “The backing of sabhas is crucial as well, because it helps in the musicians’ professional growth.”

Tribute to the maestro

The Dr. Chinnamoulana Memorial Trust, set up in 1999 by his grandsons Subhan Kasim and Subhan Babu, will be hosting its 15th ‘Shradhanjali’ (commemorative gathering) at Hotel Sangam on April 13 and 14.

At the event, the trust will be presenting nadhaswaram instruments to six deserving students this year, and for the first time, ‘thavil’ drums to three pupils, as part of the corporate social responsibility initiative of Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited (BHEL). In addition to this, a purse and citation each will be presented to senior artists Pandhanallur P.K. Ramalingam Pillai (nadhaswaram) and Needamangalam C. T. Kannappa Pillai (thavil).

Concert performances include a vocal recital by T.K. Krishna on April 13, and a nadhaswaram rendering by M. Sivadivel the next day. The event is being organised in co-operation with Rasika Ranjana Sabha, Tiruchi.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Features> MetroPlus / by Nahla Nainar / Tiruchirapalli – April 11th, 2014